Vaclav Smil - Harvesting the biosphere : what we have taken from nature

Here you can read online Vaclav Smil - Harvesting the biosphere : what we have taken from nature full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, genre: Children. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Harvesting the biosphere : what we have taken from nature

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Harvesting the biosphere : what we have taken from nature: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Harvesting the biosphere : what we have taken from nature" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Harvesting the biosphere : what we have taken from nature — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Harvesting the biosphere : what we have taken from nature" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Harvesting the Biosphere

Also by Vaclav Smil

Chinas Energy

Energy in the Developing World (edited with W. Knowland)

Energy Analysis in Agriculture (with P. Nachman and T. V. Long II)

Biomass Energies

The Bad Earth

Carbon Nitrogen Sulfur

Energy Food Environment

Energy in Chinas Modernization

General Energetics

Chinas Environmental Crisis

Global Ecology

Energy in World History

Cycles of Life

Energies

Feeding the World

Enriching the Earth

The Earths Biosphere

Energy at the Crossroads

Chinas Past, Chinas Future

Creating the 20th Century

Transforming the 20th Century

Energy: A Beginners Guide

Oil: A Beginners Guide

Energy in Nature and Society

Global Catastrophes and Trends

Why America Is Not a New Rome

Energy Transitions

Energy Myths and Realities

Prime Movers of Globalization

Japans Dietary Transition and Its Impacts (with K. Kobayashi)

Harvesting the Biosphere

What We Have Taken from Nature

Vaclav Smil

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2013 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Smil, Vaclav.

Harvesting the biosphere : what we have taken from nature / Vaclav Smil.

p.cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-262-01856-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-262-31227-1 (retail e-book)

1. Biomass.2. Biosphere.3. Natural resourcesAccounting.4. Environmental auditing.5. EarthSurface. I. Title.

TP360.S552013

333.95dc23

2012021381

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Preface

The Earths biospherethat thin envelope of life permeating the planets hydrosphere, the lowermost part of its atmosphere, and a small uppermost volume of its lithosphereis of surprisingly ancient origin: the first simple organisms appeared nearly four billion years ago (the planet itself was formed about 4.6 billion years ago), metazoan life (the first multicellular organisms belonging to the kingdom of animals) is more than half a billion years old, and complex terrestrial ecosystems have been around for more than 300 million years. Many species have exerted enormous influence on the biospheres character and productivity, none more so than (on the opposite ends of the size spectrum) oceanic cyanobacteria and the large trees of the tropical, temperate, and boreal forests. But no species has been able to transform the Earth in such a multitude of ways and on such a scale as Homo sapiensand most of these transformations can be traced to purposeful harvesting or destruction of the planets mass of living organisms and reduction, as well as improvement, of their productivity.

These transformations long predate the historical period that began about five millennia ago and was preceded by millennia of gradual domestication of wild plant and animal species and by the evolution of sedentary agriculture. Humans eventually created entirely new landscapes of densely populated areas through intensive agriculture, industrialization, and urbanization. These processes reached an unprecedented intensity and extent beginning in the latter half of the nineteenth century as industrialization was accompanied by improved food supplies, greater personal consumption, expanded trade, and a doubling of the global population in 100 years (from nearly 1.3 billion in 1850 to 2.5 billion in 1950), followed by a 2.4-fold increase (to six billion) by the year 2000. Fossil fuels have energized this latest, industrial and postindustrial stage of human evolution, whose accomplishments would have been impossible without tapping an expanding array of other mineral resources or deploying many remarkable technical innovations.

But the metabolic imperatives of human existence remain unchanged, and harvesting phytomass for food is still the quintessential activity of modern civilization. What has changed is the overall supply and the variety and quality of typical diets: increasing populations and improved standards of living have meant greater harvests of the Earths primary production, digestible photosynthates suitable for consuming directly as food crops or indirectly (after feed crops and natural vegetation are consumed by domesticated or wild vertebrates) as the milk, eggs, and meat of terrestrial animals or as the highly nutritious tissues of aquatic invertebrates, fishes, and mammals. Harvests of woody phytomass were initially undertaken to feed the hominin fires and make simple weapons. Sedentary cultures had a much greater demand for firewood (they burned crop residues, too), as well as for wood as a principal construction material. Industrialization increased such demands, and acquiring wood for pulp has been the third major motivation for tree harvests since the latter half of the nineteenth century.

The demand for food could not be met just by increasing yields but required the substantial conversion of forests, grasslands, and wetlands to new cropland. This led to a net loss of phytomass stores as well as to losses of overall primary production; in turn, some of the best agricultural lands were lost to expanding cities and industrial and transportation infrastructures. Similar losses of potential productivity have followed as substantial areas of natural ecosystems have been converted to pastures or affected by the grazing of domesticated herbivores, and as secondary tree growth or inferior woodlands replaced original forests.

Food, feed, fiber, and wood are the key phytomass categories that must be harvested to meet basic human needs. Harvests of furs, ornamental and medicinal plants, and companion animals may be important for their impact on particular ecosystems and species, but their overall removal has been (in mass terms) much smaller than the aggregate of many uncertainties that complicate the quantification of phytomass belonging to the four principal categories. The steeply ascending phase of phytomass harvests has yet to reach its peak, but I do not forecast when it may do so. Instead, I will review the entire spectrum of harvests and present the best possible quantifications of past and current global removals and losses as a way to assess the evolution and extent of human claims on the biosphere. Although some of the claims can be appraised with satisfactory accuracy, in many other cases phytomass accounting can do no better than suggest the correct orders of magnitude. But even that is useful, as our actions should be guided by the best available quantifications rather than by strong but unfounded qualitative preferences or wishes.

I

The Earths Biomass: Stores, Productivity, Harvests

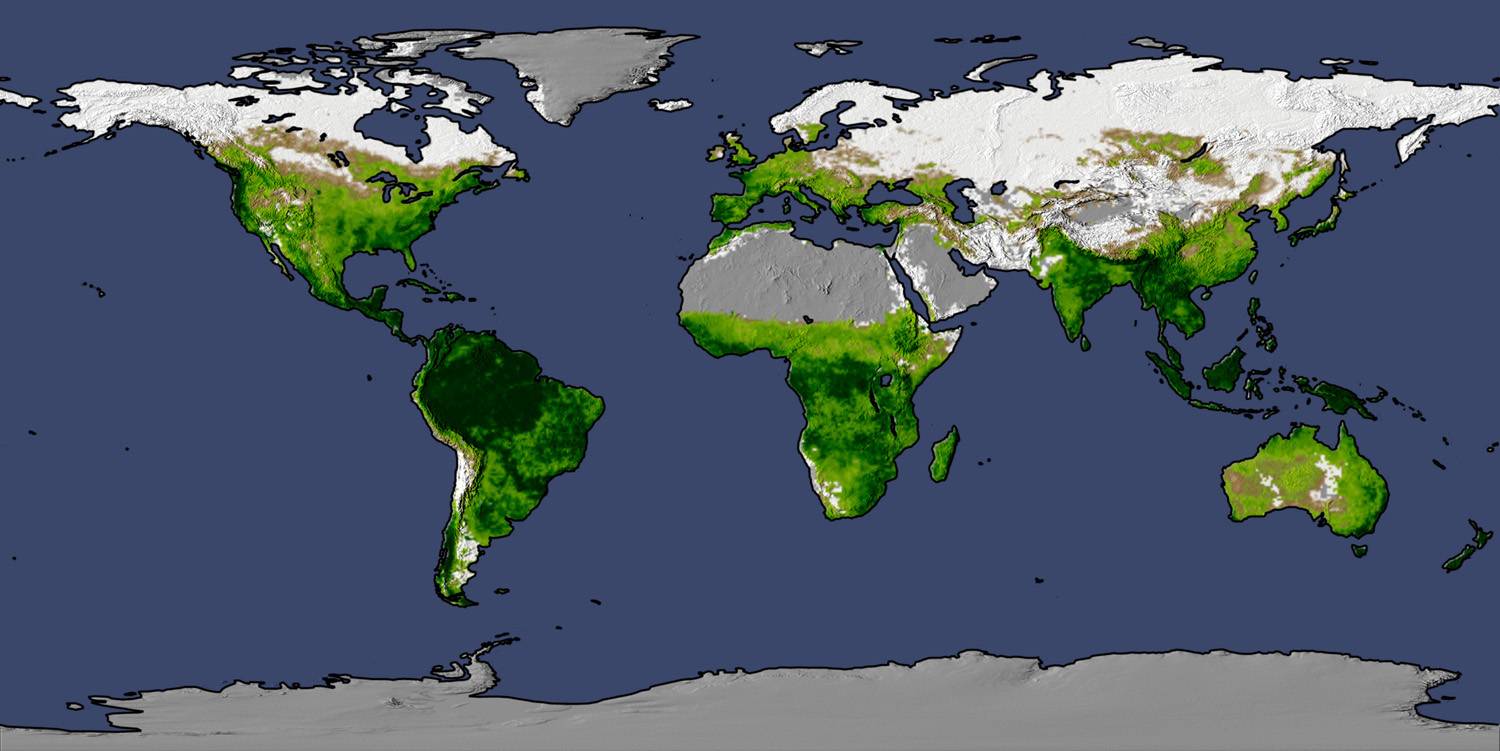

NASAs global map shows the intensity of the Earths primary (photosynthetic) productivity. The darkest shading in the Amazon and in Southeast Asia indicates net annual primary productivity approaching 1 kg C/m2.

In December 1990, the Galileo spacecraft came as close as 960 km to the Earths surface in order to get a gravitational assist from the planet on its way to Jupiter. This flyby was used by Sagan et al. (1993) as an experiment in the remote detection of life on Earth: just imagine that the spacecraft, equipped with assorted detection devices, belonged to another civilization, and registers what its beings could sense. The three phenomena indicating that this planet was very different from all others in its star system were a widespread distribution of a pigment, with a sharp absorption edge in the red part of the visible spectrum; an abundance of molecular oxygen in the Earths atmosphere; and the broadcast of narrow-band, pulsed, amplitude-modulated signals.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Harvesting the biosphere : what we have taken from nature»

Look at similar books to Harvesting the biosphere : what we have taken from nature. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Harvesting the biosphere : what we have taken from nature and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.