Mastering Chess Middlegames Alexander PanchenkoMastering Chess MiddlegamesLectures from the All-Russian School of GrandmastersNew In Chess 2015 2015 New In Chess Published by New In Chess, Alkmaar, The Netherlands www.newinchess.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. Cover design: Ron van Roon Translation: Steve Giddins Supervisor: Peter Boel Proofreading: Ren Olthof Production: Anton Schermer Have you found any errors in this book? Please send your remarks to and implement them in a possible next edition. ISBN: 978-90-5691-609-1 Contents

Mastering Chess Middlegames Alexander PanchenkoMastering Chess MiddlegamesLectures from the All-Russian School of GrandmastersNew In Chess 2015 2015 New In Chess Published by New In Chess, Alkmaar, The Netherlands www.newinchess.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. Cover design: Ron van Roon Translation: Steve Giddins Supervisor: Peter Boel Proofreading: Ren Olthof Production: Anton Schermer Have you found any errors in this book? Please send your remarks to and implement them in a possible next edition. ISBN: 978-90-5691-609-1 Contents

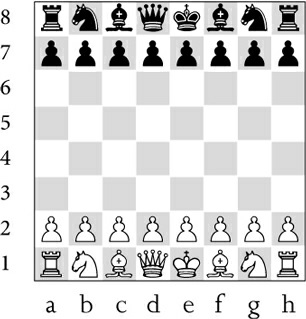

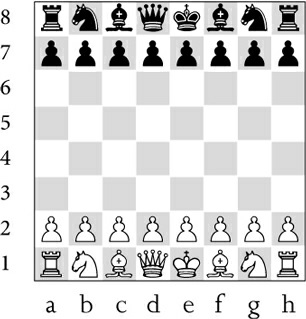

Explanation of SymbolsThe chessboard with its coordinates: White to move Black to move King Queen Rook Bishop Knight ! good move !! excellent move ? bad move ?? blunder !? interesting move ?! dubious move White stands slightly better Black stands slightly better White stands better Black stands better + White has a decisive advantage + Black has a decisive advantage = balanced position unclear # mate Preface 1980. Alexander Panchenko won a strong Chigorin Memorial in Sochi, making his second GM norm. He was in a great mood, as the nicest prospects were opening up before him.

Explanation of SymbolsThe chessboard with its coordinates: White to move Black to move King Queen Rook Bishop Knight ! good move !! excellent move ? bad move ?? blunder !? interesting move ?! dubious move White stands slightly better Black stands slightly better White stands better Black stands better + White has a decisive advantage + Black has a decisive advantage = balanced position unclear # mate Preface 1980. Alexander Panchenko won a strong Chigorin Memorial in Sochi, making his second GM norm. He was in a great mood, as the nicest prospects were opening up before him.

Then everything changed Alexander Nikolaevich himself described this turning point in his life as follows: At one moment, as my wife and I were having dinner with Yuri Balashov, Tikhomirova came over and asked to speak to me. Vera Nikolaevna explained that we needed to think about the younger generation and invited me to work as a trainer at the newly-opened All-Russian School of Grandmasters. To say that this suggestion came as a surprise would be to say nothing at all. I was just 27, and still a developing player. I was full of plans for my chess career. But he agreed and begun work.

He had a lot to learn before the first session of the school. He had to study books on teaching Korchak, Makarenko, Sukhominsky and Uspensky. He also sought advice from experienced teachers and trainers. Panchenkos trainer in Chelyabinsk was Leonid Aronovich Gratvol, a teacher from heaven. Alexander Nikolaevich remembered how he taught and tried to follow his advice. all this continued the work of V. E. E.

Golenishev, in preparing players to master level at sport. Viktor Evgenievich wrote some wonderful books a programme of preparation from Fourth Category to First, books which were reprinted numerous times but are now hard to find. Panchenko had to spend a great deal of time to prepare his lectures. In the pre-computer era, this was not so simple and it took time to collect material, think it over and prepare everything. Alexander Nikolaevich never plagiarised other peoples work, but did everything himself, from scratch. Ilyin, M. Ilyin, M.

Ackarov, T. Chitiskova, S. Shaidullina and the author of these lines; many of us became masters. The chess part of these lectures is in this book, which you, dear reader, hold in your hands. But also the way Panchenko presented the material was important, so that his pupils could absorb it and employ it in their own games. In this, he was a great master.

On the basis of the stories told by his pupils, Rublevsky, Sorokin, Scherbakov, Volzhin and others, and also my own impressions, we have tried to recreate this well-known trainers method of teaching chess. The search for chess truth was his lifes work. Alexander Nikolaevich Panchenko gave his pupils systematic knowledge in all areas of the game, and taught them to understand the game correctly. He studied fundamental positional devices and typical positions. He had them solve studies and problems (he had an excellent card-index) and often had them play out positions on the chosen theme. M. M.

Sorokin: Sometimes, one had the impression that insufficient attention was given to questions of attack, creative play generally, and the intuitive sides of chess; especial attention was always devoted to the technical side. This was despite the fact that Alexander Nikolaevich was himself an exceptionally sharp, all-round talent, who as well as many finely-judged defences, also carried out numerous sparkling attacks. He taught what was realistically possible and necessary to teach in a group situation: technique, the taking of practical decisions, but he also gave out serious individual work and gave precious advice on its organisation. He stressed individual work (or one-to-one with a permanent trainer) to develop the players individual talent. One defining characteristic of his lessons was that one did not only listen, but also had to answer specific questions. After a lesson, he would often organise a competition to solve problems on the chosen theme, with points being counted up, and then mistakes analysed afterwards.

The participants needed to show concentration and hard work, as it was not simple to absorb, understand and deeply feel a large quantity of professional-level information. In studying the middlegame, Panchenkos signature tune was the defence of difficult positions and prophylaxis. In non-chess terms, the main thing one remembers is the warmth and care he showed towards his pupils. He was interested not only in chess successes, but also devoted a great deal of attention to their general, non-chess development. I remember that after one not very successful tournament, he gave me a book by his favourite poet, Boris Pasternak, and advised me to read it and to understand what the author was saying. D. D.

Evseev told about another characteristic of Panchenko as a trainer: During lessons, the biggest comedian in the room was Alexander Nikolaevich himself. If a position involved one side having to wait passively, without undertaking anything, he coined the term scratching his leg. Or: Its better to win the queen than give mate. Of course, he meant this in the sense that it was, as a general rule, better to take material and secure a decisive advantage that way, than to calculate long and complicated variations, which might turn out not to be mating after all. But he was a sharp attacking player himself. Once, with obvious pleasure, he showed us his win over Igor Novikov in the semifinal of the USSR Championship (Pavlodar 1987), in which he carried out a beautiful attack, with many sacrifices.

Thus, on move 38, instead of taking the queen with a decisive material advantage, he played a forcing variation leading to mate. In answer to the question that he had himself said that it was better to take the queen in such cases, he smiled and said Giving mate is more fun!. Another device of Alexander Nikolaevichs was to tell little stories, about chess history, great players (with some of whom he had himself played Petrosian, Polugaevsky, Geller, etc), about his chess school, trips abroad in Soviet times, and about life in general. It was clear that he loved to talk about days gone past. He would sink back into a certain tournament or game and re-live the experience. The connection with the past and with the chess heritage occupied a significant place in the preparation of his pupils.

Next page

Mastering Chess Middlegames Alexander PanchenkoMastering Chess MiddlegamesLectures from the All-Russian School of GrandmastersNew In Chess 2015 2015 New In Chess Published by New In Chess, Alkmaar, The Netherlands www.newinchess.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. Cover design: Ron van Roon Translation: Steve Giddins Supervisor: Peter Boel Proofreading: Ren Olthof Production: Anton Schermer Have you found any errors in this book? Please send your remarks to and implement them in a possible next edition. ISBN: 978-90-5691-609-1 Contents

Mastering Chess Middlegames Alexander PanchenkoMastering Chess MiddlegamesLectures from the All-Russian School of GrandmastersNew In Chess 2015 2015 New In Chess Published by New In Chess, Alkmaar, The Netherlands www.newinchess.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. Cover design: Ron van Roon Translation: Steve Giddins Supervisor: Peter Boel Proofreading: Ren Olthof Production: Anton Schermer Have you found any errors in this book? Please send your remarks to and implement them in a possible next edition. ISBN: 978-90-5691-609-1 Contents

Explanation of SymbolsThe chessboard with its coordinates: White to move Black to move King Queen Rook Bishop Knight ! good move !! excellent move ? bad move ?? blunder !? interesting move ?! dubious move White stands slightly better Black stands slightly better White stands better Black stands better + White has a decisive advantage + Black has a decisive advantage = balanced position unclear # mate Preface 1980. Alexander Panchenko won a strong Chigorin Memorial in Sochi, making his second GM norm. He was in a great mood, as the nicest prospects were opening up before him.

Explanation of SymbolsThe chessboard with its coordinates: White to move Black to move King Queen Rook Bishop Knight ! good move !! excellent move ? bad move ?? blunder !? interesting move ?! dubious move White stands slightly better Black stands slightly better White stands better Black stands better + White has a decisive advantage + Black has a decisive advantage = balanced position unclear # mate Preface 1980. Alexander Panchenko won a strong Chigorin Memorial in Sochi, making his second GM norm. He was in a great mood, as the nicest prospects were opening up before him.