LASKERS MANUAL

OF CHESS

BY

Emanuel Lasker

WITH 308 DIAGRAMS

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

NEW YORK

Copyright 1947 by David McKay Company.

All rights reserved.

This Dover edition, first published in 1960, is an unabridged republication of the work published by David McKay Company, Inc., in 1947.

Standard Book Number: 486-20640-8

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number:

CD62-223

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

20640826

www.doverpublications.com

TO

MY DEAR WIFE

WHO SHARES WITH ME MY CARES AND LABOURS AND WHO LETS ME SHARE IN HER JOYS

The Martha Lasker Estate wishes to express its thanks to Harold M. Phillips for his efforts in making possible the publication of the present edition.

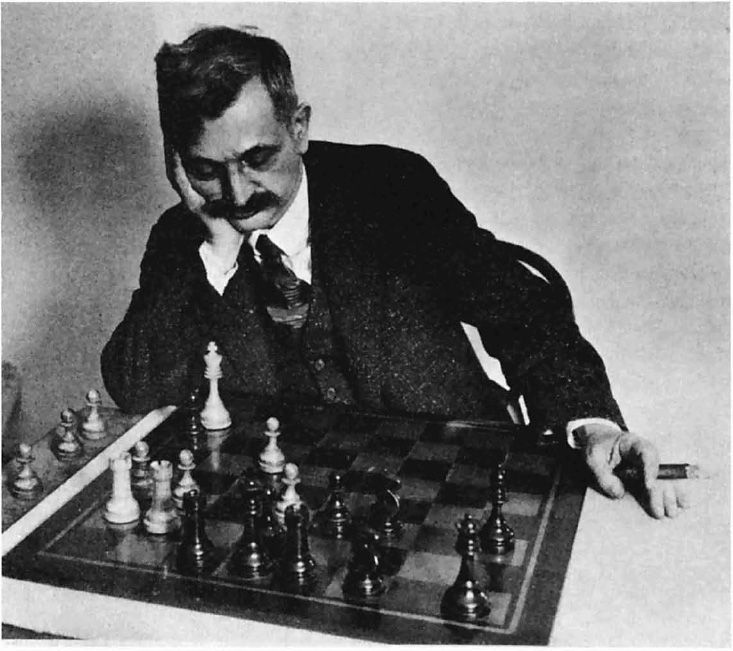

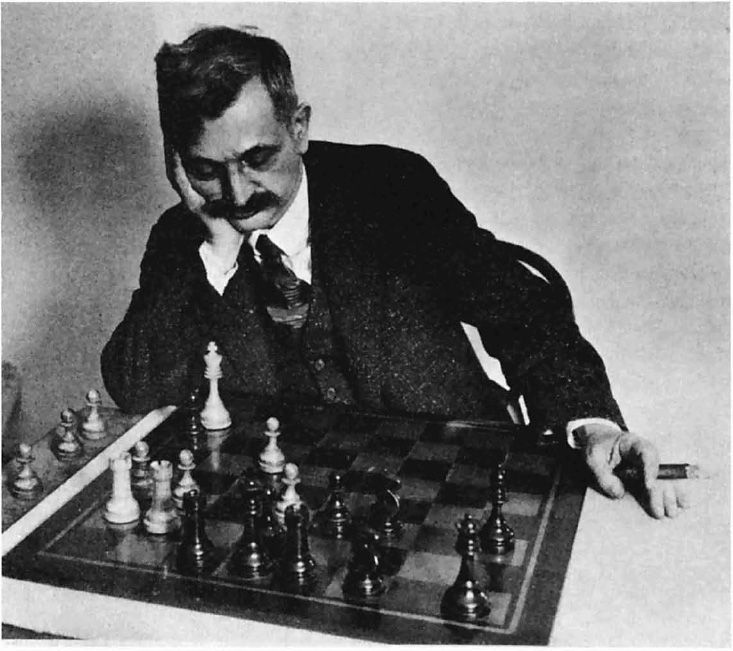

EMANUEL LASKER: AN APPRECIATION

What can be said to be permanent in this fleeting world, if not our remembrance of the deeds of great men?LUDWIG BAUER

It is a commonplace that great men are not really appreciated until death has removed them from our presence. Very few men, even very few great men, receive the homage that is rightly theirs during their lifetime. Emanuel Lasker was one of the few who become living legends; but in his case, it is a legend which is not easy to unravel. It is a legend which contains fact and fancy, unfair criticism and undiscriminating praise; a legend which depicts Lasker as shrewd and naive, as pessimistic and cheerful; a legend in which the obvious is mingled with the paradoxical.

Confronted with this confusing mass of material, it is not easy to answer the simple questions: How did Lasker become a great chess master, and in what did his greatness consist? Consider some of the difficulties: The frequently made claim that Lasker did not found a school (a claim made even by eminent masters) rests on a misconception and is in fact not true. How are we to reconcile the fact that although Lasker paid eloquent tribute throughout his life to Steinitzs theory of chess, Lasker himself followed a totally different theory? Many of Laskers games have to this day not been properly explained, in some cases because of envy, in other cases because of the annotators technical shortcomings. Yet Lasker himself frequently expressed dissatisfaction with attempts to explain the secret of his genius. Surely this is a ludicrous dilemma: how could Lasker have been World Champion for twenty-seven years without yielding up the secret of his mastery?

The best explanation of Laskers genius appears in this very book. It is still another of the many Laskerian paradoxes that the highest flights of chess genius should have been described in a book for complete beginners!

When we meet great chess-masters, we are often disappointed by their narrowness, their limitations, their pettiness. Lasker was very definitely not a man of this type; he did not live for chess alone. The reader of this book does not need to be told that Lasker devoted years of study to mathematics and philosophy at the universities of Berlin, Goettingen, Heidelberg and Erlangen. The author of the Manual reveals himself not only as a philosopher in the technical sense, but as a man of philosophical temperamenta man who has lived in many lands, read much, reflected a great deal, observed carefully but not coldly a man who knew suffering, pain, illness, disillusion, the loss of his worldly goods and the anguish of exile.

It is clear from the Manual that Laskers character and experience are mirrored in his chess, and his chess is in turn reflected in his life. No other chessmaster has insisted so strongly on the resemblance between chess and life. Most chess books deal very strictly with technical chess data; no other chess book treats non-chess material in the way that the Manual does. To Lasker there was no contradiction here; the book took on the richness, the zest and variety of life.

It is this intimate connection between Laskers life and his chess that tells us to look here for the secret of his chess genius. Lasker was a cheerful pessimist, or if you will, a moderate optimist. It was a lifelong outlook and it went into his chess. Because mathematics and philosophy played a large part in his life, they inevitably played a large part in his chess.

Laskers theory of chess can best be understood by recapitulating his account of Steinitzs theory. Before Steinitz made his investigations, master chess had a wilfully personal character. A player with a dreary, uninspired style (the kind we see in the games of Staunton, Wyvill and other English masters of the mid-nineteenth century) produced dreary, uninspired chess. The great combinative geniuses (Morphy, Anderssen, Kolisch and their followers) produced delightful combinations whose artistry still gladdens us.

It was left to Steinitz to explain that advantages and disadvantages on the chess-board exist objectively and are conditioned by the situation actually on the board; that this situation, the relationship of forces, determines the proper plan to be followed; that the execution of this plan must make victory possible. As Lasker emphasizes in this book, planning is possible only on the basis of general rules rules that sum up the lifetime experience of thousands of players. Without this inductive method, chess would sink back into the brute chaos of the physical world.

This rational quality of chess seems to have had a great fascination for Lasker. Again and again we find such statements in his book as Reason which governs the world governs also the chessboard. (Here we see Lasker in the role of rather naive optimist. As a child of the nineteenth century, he could not resist the absurd thesis that in the long run, the world improves by a series of short-term catastrophes.)

In Life, he says, we are all duffers. In Life we are all checkmated, sooner or later; in chess, we can bring off many successes which are inherent in the rational nature of the game. So, On the chessboard lies and hypocrisy do not survive long. The creative combination lays bare the presumption of a lie; the merciless fact, culminating in a checkmate, contradicts the hypocrite. Our little chess is one of the sanctuaries, where this principle of justice has occasionally had to hide to gain sustenance and a respite, after the army of mediocrities had driven it from the market-place.

But it would be a mistake to think that Steinitz succeeded in giving chess an exclusively rational character. In an article in Chess Review, I once described Steinitz and his great contemporary Tchigorin in these terms: These two geniuses had an unrivalled insight into the nature of chess. Whereas the popularizers think of chess as being amenable to order, logic, exactitude, calculation, foresight and other comparable qualities, Steinitz and Tchigorin agreed on one thing: that chess can be, and often is, as irrational as life itself. It is full of disorder, imperfection, blunders, inexactitudes, fortuitous happenings, unforeseen consequences. But whereas Steinitz strove with all his might to impose order on the irrational, Tchigorin went to the other extreme. Let us surrender to the irrational, he said in effect. Steinitz tried to banish the unforeseen. Tchigorin took delight in it. Steinitz sought order, system, logic, balance, broad basic postulates; Tchigorin wanted surprise, change, novelty, glitter, the lightning stroke from a clear sky.

In studying this contrast, we begin to sense the wide divergence between Laskers praise of Steinitz and the way that Lasker played chess! Lasker wrote his tribute to Steinitz in so generous a mood that he omitted several failings of the Steinitzian system. Steinitz was above all a doctrinaire, a fanatic. He never took account of human weakness and imperfection. If an idea fitted into his system, it had to be right. If he lost a million times with the move, it was still right, but something else had gone wrong. Steinitz never pleaded his own physical weakness, his misery, his poverty, his loneliness as extenuating factors. They were ruled out by his system. Only what was on the board counted. He wanted general laws, he loathed the exceptions. It is doubtful whether in Steinitzs view there could be such a thing as an exception. Had Steinitz been told that much of his success was due to his passion for the game, his tenacity, his resourcefulness, his faith, his imagination at all this he would have gaped.

Next page