Freedoms Orphans

NEW FORUM BOOKS

Robert P. George, Series Editor

A list of titles in the series appears at the back of the book

Freedoms Orphans

CONTEMPORARY LIBERALISM AND THE FATE OF AMERICAN CHILDREN

David L. Tubbs

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2007 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data

Tubbs, David Lewis, date.

Freedoms orphans : contemporary liberalism and the fate of American children / David L. Tubbs.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eISBN 978-1-40082-807-4

1. Child welfareUnited States. 2. LiberalismUnited States. I. Title.

HV741.T83 2007

362.7dc22 2007001484

British Library CataloginginPublication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon

Printed on acidfree paper.

pup.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my mother and father

Contents

Acknowledgments

For comments on different chapters, including drafts, I thank James Wood Bailey, Sotirios Barber, Sammy Basu, Aurelian Craiutu, Patrick Deneen, Caryl Emerson, John Finnis, Michael Frank, David Innes, Edward Keynes, Andrew Koppelman, Yvan Lengwiler, Shannon Masterson, Jacqueline Pfeffer Merrill, Thomas Merrill, Randall Miller, Jack Nowlin, Hilary Persky, Daniel Robinson, Martha Whitfield, Peter Wood, and Michael Zuckert. An anonymous reader for Princeton University Press also read the manuscript and made many valuable suggestions.

For discussing different themes and answering questions for me, I am grateful to Gerard Bradley, Paolo Carozza, Ilene Cohen, Norman Fost, Mary Ann Glendon, Kim Hendrickson, M. Cathleen Kaveny, John Keown, Olga Keyes, Stanley Kurtz, Christopher Levenick, David Novak, Stan Oakes, David Oakley, and A. A. Sharogradskaya.

I received much help in locating sources for Chapter Four from Mr. Dwight King, a superb law librarian. Laura Leslie also provided research assistance with that chapter and others.

My biggest debts are to three former professors, each of whom influenced this project in different ways.

George Kateb is an extraordinary teacher. Despite our disagreements about the matters explored in this book, he was characteristically generous with his comments in response to my arguments here. Those comments often forced me to rethink matters large and small, and whatever the books shortcomings, it is much better as a result of his engagement with it.

I owe a special thanks to George Downs for so much encouragement and good counsel, without which it is unlikely that I ever would have finished the book. He read multiple drafts of each chapter, and he was always ready to converse (or spar) with me about any point. The breadth of his knowledge of the social sciences amazes me, and I often availed myself of it.

I am flattered that Robert George wanted this book to be part of his series at Princeton University Press, and I hope that his confidence is justified. I thank Robby for his enthusiasm about this project and for providing guidance at the beginning. Thereafter, I benefited at every stage from his formidable knowledge of constitutional law and legal theory.

I have received institutional support from several sources. Having spent a year at the American Enterprise Institute as the W. H. Brady Visiting Fellow in Social and Political Studies, I wish to thank Chris DeMuth,the President of AEI, the sponsors of the fellowship, and Sam Thernstrom, who directs the Brady Program on Culture and Freedom. After my year at AEI, I received a faculty research grant from the Earhart Foundation. I thank Ingrid Gregg, its president, and Kim Dennis, who first told me about the research grants. Finally, I am grateful to Luis Tellez and the other officers of the Witherspoon Institute for their continuing support.

An earlier version of Chapter Four appeared in Pepperdine Law Review 30, no. 1 (2002): 178, 2002 by the Pepperdine University School of Law. I gratefully acknowledge permission to reprint this here.

Freedoms Orphans

INTRODUCTION

CHILDREN DEPEND on adults for many things, and this dependence encompasses more than material needs. Certain intangible goodseducation, for exampleare just as crucial to their well being. These observations are hardly provocative, and any sustained commentary on human society that wants to be taken seriously is unlikely to deny this dependence.

In this connection, consider the second of Ralph Waldo Emersons two epigraphs to his essay Self-Reliance (1841):

Cast the bantling on the rocks,

Suckle him with the shewolfs teat;

Wintered with the hawk and fox,

Power and speed be hands and feet.

The irony of these lines serves several purposes. It points to the limits of selfreliance, perhaps as a way of tempering the enthusiasm of those readers well disposed to the essay. At the same time, the epigraph forestalls possible criticisms. Without it, some readers might complain that Emerson has forgotten about children and family life, an otherwise startling omission in a disquisition about the individuals relationship to society.

Besides being dependent on adults, children are impressionable. By definition, a child is underdeveloped in several ways: physically, mentally, morally, and emotionally. To say that an adult is mentally, morally, or emotionally underdeveloped often implies that he or she is also impressionable. In adults, such impressionability is considered regrettable (and sometimes a grave misfortune), but with respect to children, it is deemed unexceptional or natural.

These two themes are not unrelated. For good and for bad, a childs impressionability is in some ways linked to his or her dependence on adults.

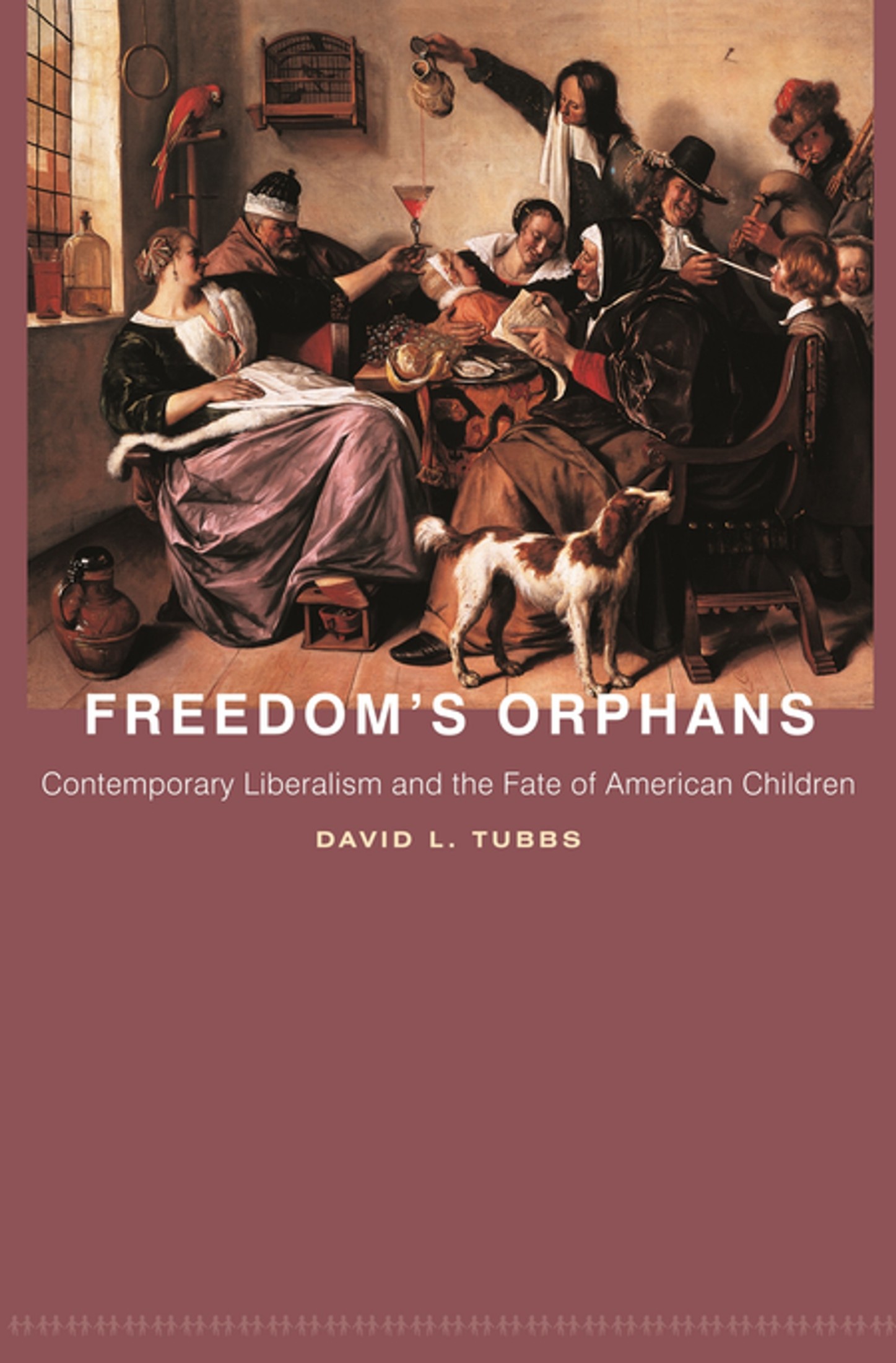

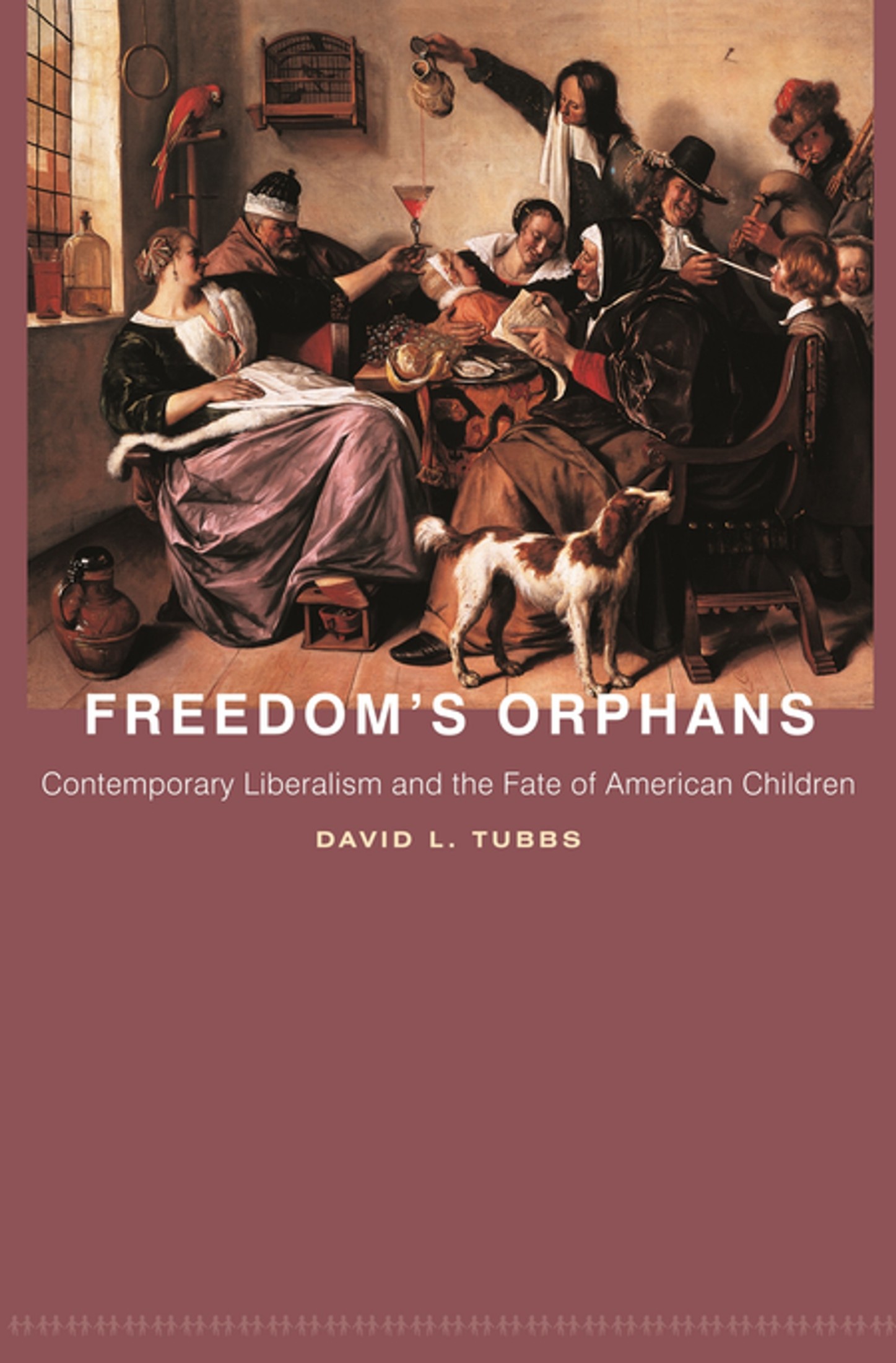

Nearly two hundred years before Emersons SelfReliance, the Dutch artist Jan Steen (16261679) completed a semihumorous painting, TheWay You Hear It Is the Way You Sing It. Like many Dutch works of the seventeenth century, it is rich in symbolism, though what the painting says about moral education, human appetites, and the impressionability of the young is clear.

The painting depicts a family of three generations gathered for the festival of Twelfth Night. The grandfather of the family, a rotund man who has been crowned king of the festival, sits at the head of a small table set with holiday fare. Above the grandfather, an uncaged parrot, symbolizing mimicry, rests on its perch. The grandfathers wife sits across from him at the table and reads a nursery rhyme of the same title as the painting. Two younger women, perhaps the couples daughters, sit between the grandfather and grandmother. The younger woman in the background has a baby in her lap. The younger woman in the foreground, only slightly less corpulent than the grandfather, holds a large goblet, being filled with the same liquid that seemingly caused her drunkenness. A beaker of this liquid stands on the windowsill.

Away from the table, on the right side of the painting, an apparently tipsy man stands near two boys and an adolescent playing the bagpipes. Thought by some scholars to be Steen, the man is showing the older of the two boys how to smoke a long and slender pipe; the younger boy awaits instruction. Behind him, the adolescent with the bagpipes plays a tune. His face appears flush, a detail whose meaning can be appreciated in light of the sexual innuendo associated with the Dutch word for pipe.