Contents

Guide

Copyright 2005, 2020 by Derek Madden

First Heyday edition 2005, originally titled Magpies and Mayflies: An Introduction to Plants and Animals of the Central Valley and Sierra Foothills

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Heyday.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Madden, Derek, author, illustrator. | Charters, Ken, author. | Madden, Erinn, author.

Title: The naturalists illustrated guide to the Sierra Foothills and Central Valley / Derek Madden with Ken Charters and Erinn Madden ; illustrated by Derek Madden.

Description: [Revised edition]. | Berkeley, California : Heyday Books, [2020] | First Heyday edition 2005, originally titled Magpies and Mayflies: An Introduction to Plants and Animals of the Central Valley and Sierra Foothills.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019057785 (print) | LCCN 2019057786 (ebook) | ISBN 9781597144865 (paperback) | ISBN 9781597144971 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Natural history--California--Central Valley.

Classification: LCC QH105.C2 M15 2020 (print) | LCC QH105.C2 (ebook) | DDC 508.794/5--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019057785

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019057786

Illustrations by Derek Madden

Cover Art: Derek Madden

Cover Design: Ashley Ingram

Interior Design/Typesetting: Ashley Ingram

Published by Heyday

P.O. Box 9145, Berkeley, California 94709

(510) 549-3564

heydaybooks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Sierra and the World of Wonder

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Californias central valley is a vast region, spanning nearly 450 miles, where waterways crease a landscape of grasslands, orchards, and cities, from Bakersfield in the far south to Redding in the north. Rising up from this vale is a rim of rolling foothill savannahs that resemble the great upland plains of East Africa. A break in this rim lies at the Delta, where a labyrinth of braided waterways, islands, and marshes mark the flow of inland rivers colliding with the waters of the Pacific ocean. This land of little rain was occupied in prehistoric times by enormous inland seas and later fostered great civilizations of Native Americans. In more recent times, fieldworkers and landless farmers immigrated to this vale to escape Midwestern dustbowls, a pattern repeated by newer arrivals from across our Southern border and even from across oceans. Theyve come to scrape together a life in the booming croplands and orchards and on the railroads and trucking routes that connect this fertile hub to its far-flung markets.

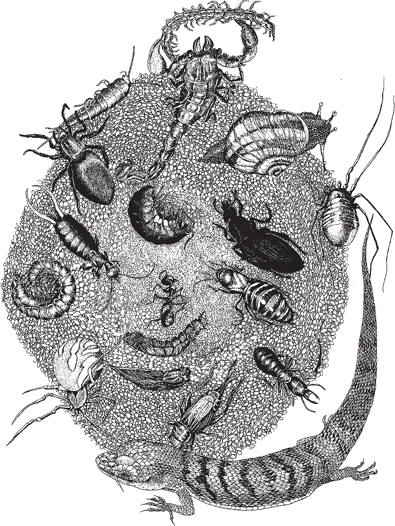

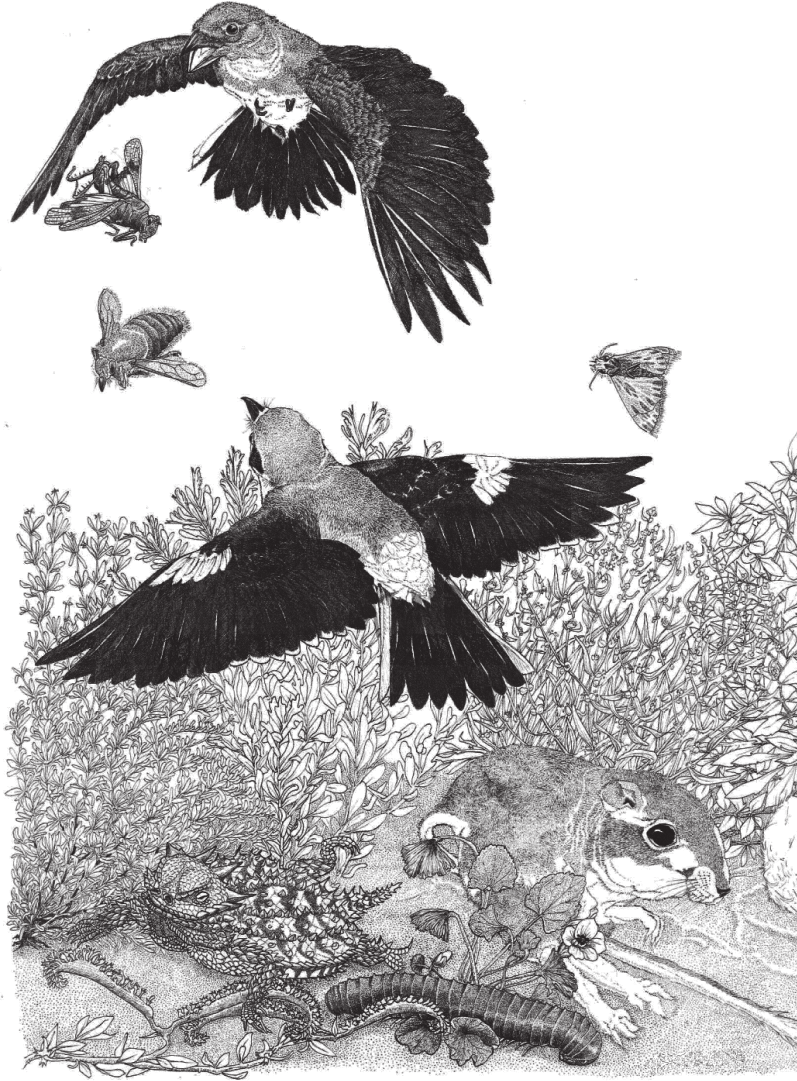

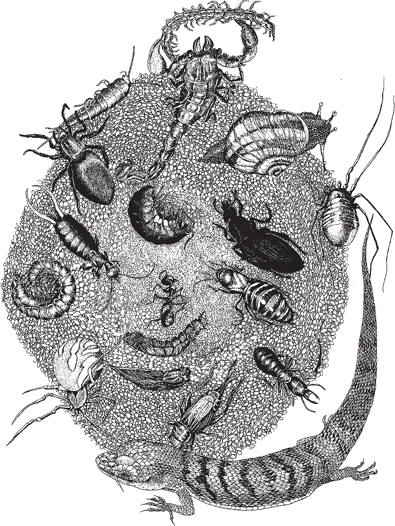

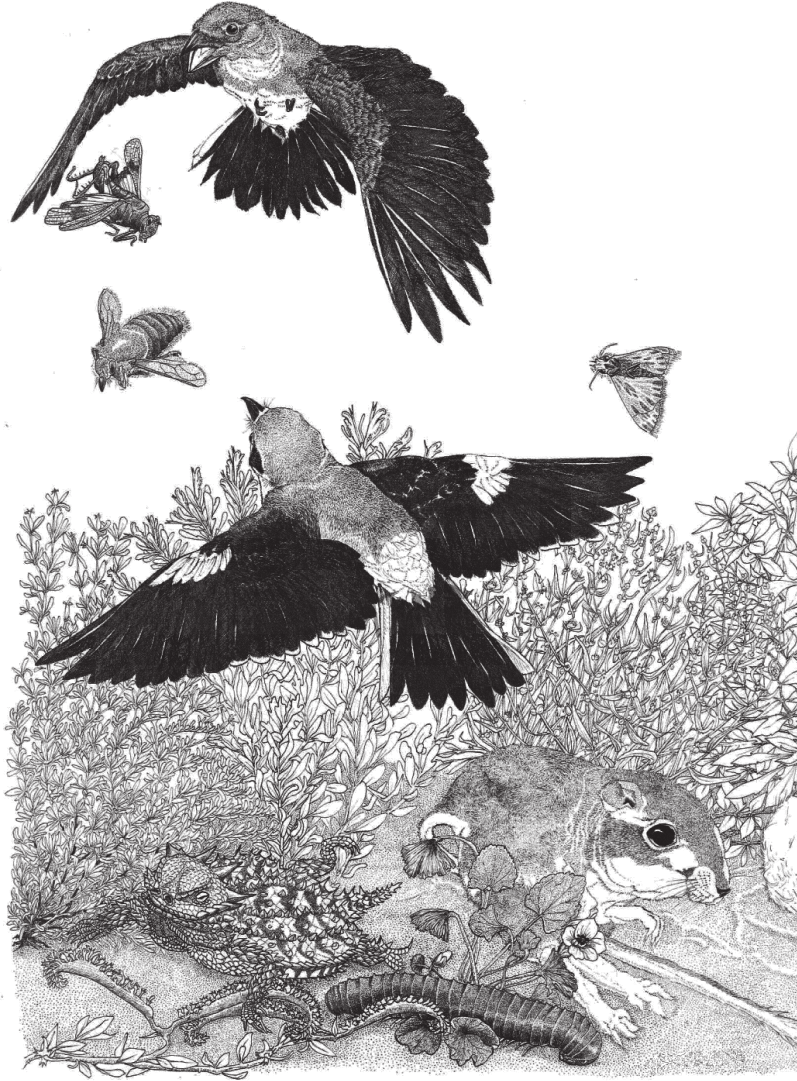

Today, the predominant landscape of the Central Valley and Sierra Foothills is still broad spreads of field and tree crops, though now the farms are often edged by housing estates. Suburban development has come to the Sierra foothills as well. Throughout the Valley/Foothill region, grazing livestock, fires, and the introduction of plants and animalssome invasive, some less sohave altered the native landscape irreparably. Yet Californias central valley is a place that continues to teem with life: the Valley is a migratory corridor for birds on the Pacific Flyway and for several species of fish; habitats for bizarre creatures from horned lizards to kangaroo rats to freshwater jellyfish abound. To this day, the deep riverside forests and vast oak savannahs of the region resound with the cries of woodpeckers and the screeches of hawks.

The Naturalists Illustrated Guide to the Sierra Foothills and Central Valley introduces the plants and wildlife of this enormous region. We include facts that delight and astound: did you know that an otter has a thousand hairs per square inch of skin, or that lizards can detach their tails in order to distract predators? The tails of some species can continue to wriggle for up to an hour. To some extent, this is a historic guidebook, describing a fabulous array of creatures that once roamed in great numbers and still exist where they can in backyards, vacant lots, and reserved parks across this land.

A note of caution: eating wild plants and fungi is inherently risky. The publisher and authors are not responsible for any adverse effects or consequences that might result from the consumption of toxic wild substances. Information contained in these pages is based on scientific literature and several decades of our own fieldwork, and it has been reviewed by experts in various fields of science. However, our approach here is to showcase stories of the marvelous life forms that inhabit this region in order to share this ecological diversity with all those who treasure their wild neighbors here in central California.

Among the many people who have helped us are David Aurora, Harold Basey, Arnold Chavez, Teri Curtis, Sarah Davis, Tana Dennen, David Grubbs, Lynn Hansen, Tim Heyne, Carl Johansson, Maxine Madden, Sierra Madden, David Martin, Malcolm Margolin, Elizabeth McInnes, Cathy Snyder, staff at the Great Valley Museum, Catherine Tripp, Lillian Vallee, Guy VanCleave, and Criss Wilhite. David Lukas, for thoughtful comments on the Heyday edition, deserves special mention, as do editor Jeannine Gendar, designer Ashley Ingram, and art director Diane Lee. Thanks to Marthine Satris for her editorial precision and creativity during publication production. And for their generous support of this project, we thank James McClatchy and the Strong Foundation for Environmental Values.

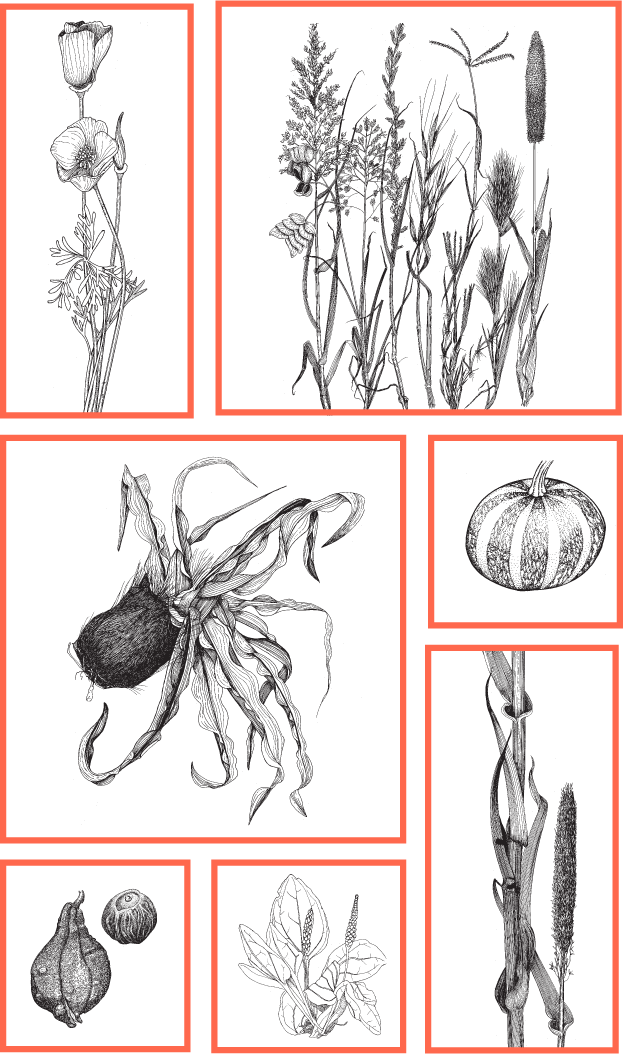

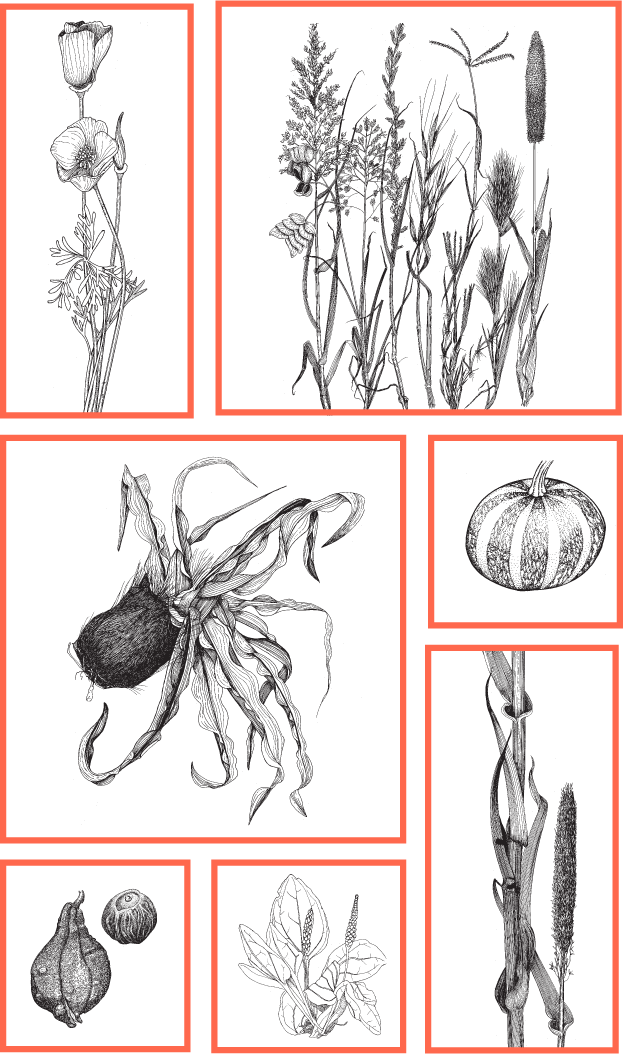

PLANTS

Plants with Spores

As different as ferns and mosses appear to be, they share the same basic need: water, and lots of it.1 Anchored in dampness near leaky gutters and riverbanks, they thrive on the shady side of life. Their ancestors may have fed dinosaurs, but those larger plants disappeared along with the prehistoric swamps; in our dry habitats today, ferns and horsetails rarely grow over four feet tall. Mosses dont grow much taller than a shag carpet.

The reason ferns are so much larger than mosses lies in the vascular system that transports water and nutrients within a plant. Although seedless and primitive, ferns have a network of vascular tubes that enable large growth. Rootless and lacking a good vascular system, mosses get a limited amount of water because they must absorb it through whatever part of the plant is wet.

When moss plants are wet, their specialized leaf cells swell like water balloons; moss holds nearly twenty times its dry weight in water, which puts cotton to shame when it comes to absorbency. Because of their legendary water-holding capacity, mosses have been used as bandages and for gardening soil in many cultures. Sterilized moss was the nurses bandage of choice during World War I. It was gradually replaced as hospitals switched to white cotton for its reassuringly clean appearance.