All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without either prior permission in writing from the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying. In the United Kingdom such licences are issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Barnards Inn, 86 Fetter Lane, London EC4A 1EN

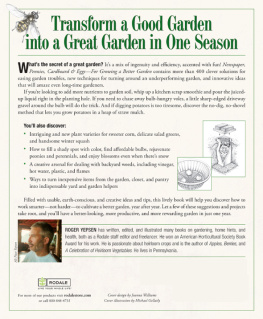

I would never have imagined, when working on the first edition of The Salad Garden in the early 1980s, that I would be revising it again in 2016, in my eighties. What a thrill to find so many people, young and old, not just eating more salads, but discovering the joy and satisfaction of growing their own, marvelling at the taste of freshness and the diverse flavours and colours that can emerge from even a flower pot on a patio. And almost invariably, growing organically.

In the introduction to the 2001 edition (shown ) I outlined the journey salad growing has taken our family on, from an allotment plot to an experimental market garden with several little potagers in Suffolk. And now a new chapter has opened. In 2002 we uprooted ourselves to retire to County Cork in the south-west corner of Ireland. In the years since, our energies have been channelled into converting a windswept field into a fan-shaped potager. The final project I promised my husband Don it would be the final project was to make a small raised bed potager near the house. This has become our new salad garden.

Its core is two pairs of rectangular raised beds built from recycled plastic, 1/m/4ft wide, 3m/10ft long and 75cm/30in high, so easily reached without bending down or kneeling. At either end two semi-circular, stone walled beds gently round off the area, with an irresistible stone seat set in each. All the beds are linked with rebar arches covered with sheep wire, where sweet peas, honeysuckle, climbing beans, pumpkins, blackberries and other fruit clamber. This is the setting for our salads. I love it.

We also grow salads in the small greenhouse attached to the house, mainly tomatoes in summer, and in winter seedling salads, oriental and Texsel greens, spinach and endives. It is always full.

The past thirty years have seen many changes in varieties available to home gardeners. In this new edition Ive drawn on advice from knowledgeable specialists, and the trials carried out by the Royal Horticultural Society, to suggest the best of what is available for todays salad growers. Where possible, Ive included compact varieties bred for smaller gardens and containers, as well as varieties with decorative qualities. After all, salad plants have to feed the body and the spirit.

Introduction

It is almost impossible to believe, from the viewpoint of the twenty-first century, how my garden and gardening ideas have changed since I first started growing vegetables seriously in the 1970s. Then my garden was a very plain plot (an allotment in fact), whereas today our Suffolk kitchen garden includes several picturesque little potagers each carefully designed to have shape, colour and form all year round. Way back then the salad plants we grew could be counted on the fingers of one hand; lettuce, tomatoes, cucumbers, radish Today, during the course of two or three seasons, we grow well over 150 salad plants.

Finding these plants and learning how to grow them has been a long and wonderful voyage of discovery. Its first leg was what we fondly called our Grand Vegetable Tour. In August 1976, my husband Don Pollard and I, with our children Brendan and Kirsten, who were then seven and five years old, left Montrose Farm for a year to travel around Europe in a caravan. Our main purpose was to learn about traditional and modern methods of vegetable growing, and to collect the seed of local varieties of vegetables, which, as a handful of far-sighted people had begun to appreciate, were an invaluable genetic heritage that was vanishing fast.

). This extends from cutting broadcast patches of seedlings up to five times, to cutting mature heads of chicory, endive and lettuce and leaving the stumps to resprout for further pickings. We returned home eager to try out these new plants and ideas.

Shortly afterwards I was asked to take part in an exhibition on the history of English gardening at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, and this led me to old English gardening books, a hitherto unknown world to me. I discovered John Evelyns Acetaria: a Discourse of Sallets, written in 1699, and his Directions for the Gardiner at Says Court, compiled a few years earlier; I also discovered Batty Langleys New Principles of Gardening (1728) and other seventeenth- and eighteenth-century classics. One day in the British Museum I tracked down a frail, handwritten, fifteenth-century cookery book, with one of the earliest known lists of herbes for a salade. These books were a revelation, for here were lists, written hundreds of years ago, of the sort of salad plants we had found still being cultivated on the Continent, along with instructions for growing seedling crops, for forcing and blanching salad plants for winter use, for gathering plants from the wild, and even for using flowers, flower buds and shoot tips in salads, either fresh or pickled for winter.

At about the same time, suspecting another untapped treasure trove of useful salad plants, I began to try out some of the Chinese and Japanese vegetables that were becoming available through enterprising seed catalogues. This proved to be the start of a ten-year odyssey, taking me to China, Taiwan, Japan and later to the USA and Canada, unravelling the mysteries of Asian vegetables. The fast-growing leafy greens, above all, came to play a key role in our own salad making.

On our return from our European travels, we turned our garden into a small, experimental market garden run on organic principles. We supplied unusual vegetables to wholefood and health shops, our speciality being bags of mixed fresh salads, which we called saladini. Even though our winter temperatures were often as low as -10C/14F, we found that it was quite possible, using unheated polythene tunnels, to grow fresh salads all year round. We usually managed to produce at least twenty different types of plant for each bag.