Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my girls

(who called me Gilderoy)

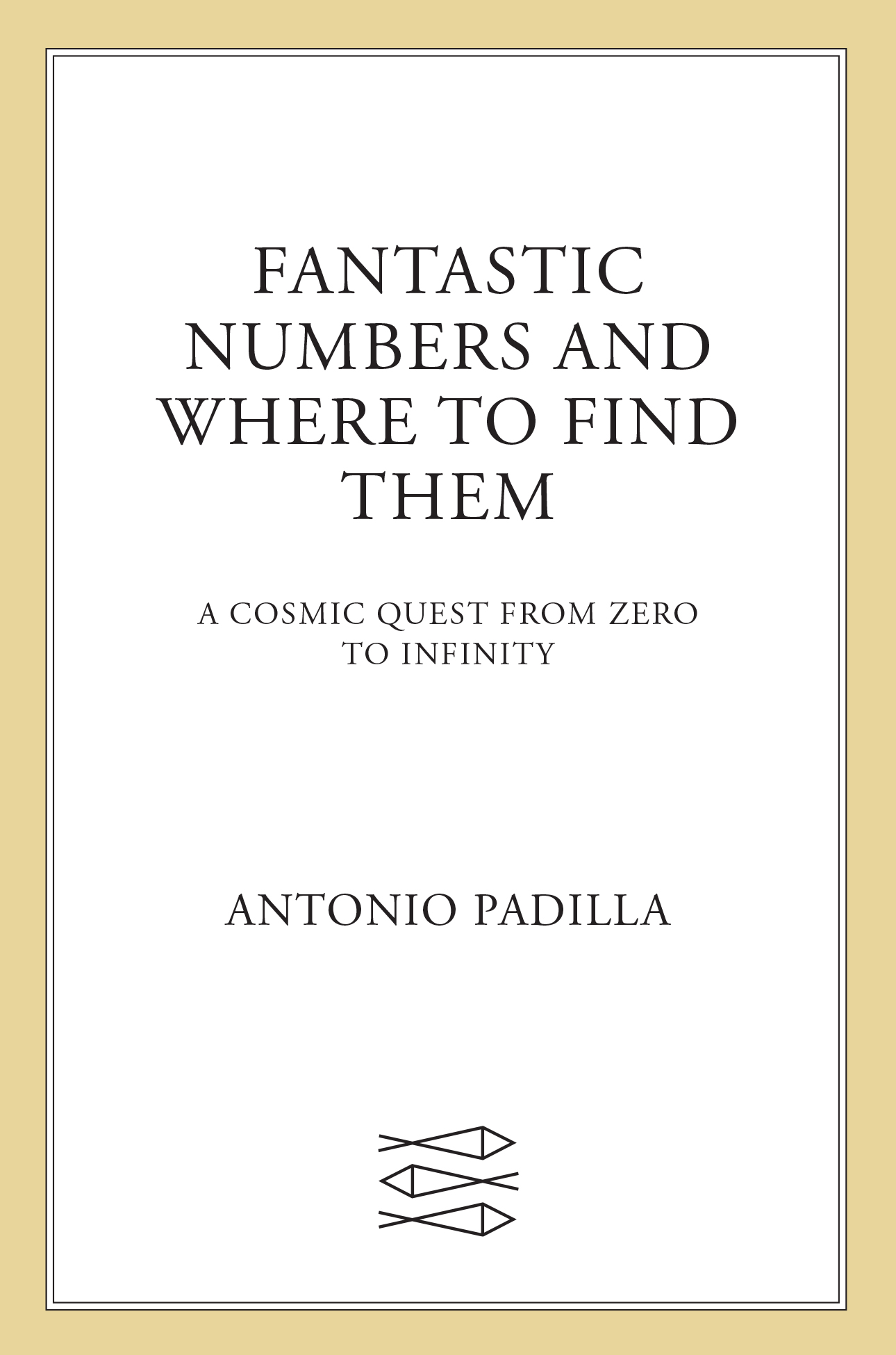

The number lay there, brazen, taunting me from the tatty piece of paper that sat neatly on the ancient oak table: zero. Id never scored zero in a maths test before but there was no mistaking my mark. The number was scrawled aggressively in red at the top of the coursework Id handed in a week or so earlier. This was in my first term as a mathematics undergraduate at Cambridge University. I imagined the ghosts of the universitys great mathematicians whispering their contempt. I was an imposter. I didnt know it at the time, but that coursework would prove to be a turning point. It would change my relationship with both maths and physics.

The coursework had involved a mathematical proof. These usually begin with some assumptions and, from there, you infer a logical conclusion. For example, if you assume that Donald Trump was both orange and President of the United States, you may infer that there has been an orange President of the United States. My coursework had nothing to do with orange presidents, of course, but it did involve a series of mathematical statements that Id connected with a clear and consistent argument. The Cambridge don agreed all the arguments were there but he had still given me a zero. It turned out his issue was with how Id laid it all out on the tatty piece of paper.

I was frustrated. Id done the hard part in figuring out the solution to the coursework problem, and his complaint seemed petty. It was as if Id scored a spectacular goal, only for the don to check with the Video Assistant Referee and rule it out for a marginal offside. But I now know why he did it. He was trying to teach me about rigour, trying to instil the mathematical pedantry that is an essential part of a mathematicians toolkit. Reluctantly, I became a pedant, but I also realized then that I needed a little more from mathematics. I needed it to have personality. Id always loved numbers, but I wanted to bring them to life to give them a purpose and for that I found that I needed physics. That is what this book is all about the personality of numbers shining through in the physical world.

Take Grahams number as an example. This is a leviathan, a number so large that it once had pride of place in the Guinness Book of World Records as the largest number ever to appear in a mathematical proof. It is named after the American mathematician (and juggler) Ron Graham, who was wonderfully pedantic in making mathematical use of it. But his pedantry is not what brings Grahams number to life. What brings it to life or perhaps more accurately, death is physics. You see, if you were to try and picture Grahams number in your head its decimal representation written out in full your head would collapse into a black hole. Its a condition known as black hole head death and there is no known cure.

In this book, Im going to tell you why.

In fact, Im going to tell you more than why. Im going to take you to a place where you will question things youd always assumed to be true. This journey through Fantastic Numbers will begin with the biggest numbers in the universe and a quest to understand what is known as the holographic truth. Are three dimensions just an illusion? Are we trapped inside a hologram?

To understand this question, punch the air around you. You should probably make sure you arent sitting too close to anyone, but punch forwards and backwards, left and right, and up and down. You can punch your way through three dimensions of space, three perpendicular directions. Or can you? The holographic truth asserts that one of these dimensions is a fake. It is as if the world is a 3D movie. The real images are trapped on a two-dimensional screen, but when the audience puts on their glasses a 3D world suddenly emerges. In physics, as I will explain in the first half of this book, the 3D glasses are provided by gravity. It is gravity that creates the illusion of a third dimension.

It was only by taking gravity to its extreme that we became aware of its sorcery. But then this is a book of extremes. Our quest to understand the holographic truth begins, inevitably, with Albert Einstein, his genius, the perverse brilliance of relativity and the underlying structure of space and time. Of course, I have a number for his genius: 1.000000000000000858. And yes, Im calling this a big number. I imagine you are sceptical, but hopefully Ill convince you that it is a huge number, at least if you think about the physics it represents: one mans ability to meddle with time. To really understand why, well need to run alongside the legendary Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt. Well need to plunge to the depths of the Pacific Ocean, to the deepest part of the Mariana Trench. Well have to go to the edge of physics, dancing dangerously close to a monstrous black hole as it guzzles greedily on the stars and planets at the centre of a distant galaxy.

But relativity and black holes are just the beginning. To find the holographic truth, we will need four more leviathans genuine numerical gargantua that come to life whenever they collide with the physical world. From a googol to a googolplex, from Grahams number to TREE (3) , these are the titanic numbers that will appear to break physics. But the truth is they will guide us in our understanding. They will teach us the meaning of entropy, so often misunderstood, which describes the turbulent physics of secret and disorder. They will introduce us to quantum mechanics, the lord of the microworld, where nothing is certain and everything is a game of chance. The story will be told with tales of doppelgngers in far-off realms and warnings of a cosmic reset, when everything in our universe returns, inevitably, to the way it once was.

In the end, in this land of giants, we will find it: a holographic reality. Our reality.

I am a child of the holographic truth. It was an idea that took off around the time I scored zero in my coursework, although I knew nothing about it back then. By the time I started my doctorate about five years later, it was fast becoming the most important idea to be developed in fundamental physics in almost half a century. Everyone in physics seemed to be talking about it. Everyone is still talking about it. They are asking deep and important questions about black holes and quantum gravity and, in the holographic truth, they are finding answers.

There was something else everyone was talking about back then, as we were getting ready to usher in a new millennium: the mystery of our finely tuned and unexpected universe. You see, ours is a universe that simply should not exist. Its a universe that has let us live, that has given us a chance of survival, against all the odds. Its where we will go in the second part of this book, guided not by leviathans but by the mischief-makers the little numbers.

Little numbers betray the unexpected. To understand this, imagine me winning The X Factor. I cannot stress how unexpected this would be, because Im a terrible singer, so awful that in a high-school musical I was asked by the teachers to stand away from the microphones. With this in mind, I would say that the probability of me winning a national singing competition is somewhere in the region of the following number: