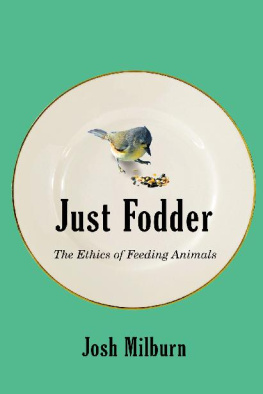

Just Fodder

Just Fodder

The Ethics of Feeding Animals

Josh Milburn

McGill-Queens University Press

Montreal & Kingston London Chicago

McGill-Queens University Press 2022

ISBN 978-0-2280-1135-4 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-2280-1151-4 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-2280-1323-5 (e PDF )

ISBN 978-0-2280-1324-2 (e PUB )

Legal deposit second quarter 2022

Bibliothque nationale du Qubec

Printed in Canada on acid-free paper that is 100% ancient forest free

(100% post-consumer recycled), processed chlorine free

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Just fodder : the ethics of feeding animals / Josh Milburn.

Names: Milburn, Josh, author.

Description: Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20220156212 | Canadiana (ebook) 20220156247 | ISBN 9780228011514 (paper) | ISBN 9780228011354 (cloth) | ISBN 9780228013235 (e PDF ) | ISBN 9780228013242 (e PUB )

Subjects: LCSH : Animal feeding Moral and ethical aspects. | LCSH : Animal welfare Moral and ethical aspects. | LCSH : Animal rights Moral and ethical aspects. | LCSH : Human-animal relationships Moral and ethical aspects.

Classification: LCC HV 4708 . M 55 2022 | DDC 179/.3 dc23

This book was designed and typeset by Peggy & Co. Design in 11/4 Sabon.

Contents

Acknowledgments

I began thinking about problems around the ethics of feeding animals while reading for a PhD in the School of Politics, International Studies, and Philosophy at Queens University Belfast ( QUB ), where I was supervised by Dave Archard and Jeremy Watkins and funded by Northern Irelands Department of Employment and Learning. For prompting me to think about food, I thank Matteo Bonotti, a QUB colleague, and, for prompting me to think specifically about the feeding of animals, I thank Katherine Wayne, whom I met at the MANCEPT Workshops.

This book was conceived and (mostly) written during my postdoctoral fellowship at Queens University ( QU ). This fellowship was funded partially by a grant from the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. During this fellowship, I was based in the Department of Philosophy and mentored by Will Kymlicka. Both Will Kymlicka and Sue Donaldson read and commented on draft chapters and discussed ideas in this book with me on numerous occasions. I am very thankful to them, as well as the wider Department of Philosophy and APPLE research group. Ideas from the book were presented at QU on several occasions, and I thank all those who engaged with them.

Further work on the book was completed after my time at QU , first while I was teaching in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of York (when I presented some ideas from the book at the MANCEPT Workshops), and then while I was a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Sheffield (grant number PF 19/100101). I offer particular thanks to Alasdair Cochrane, my mentor at Sheffield, who was good enough to read numerous drafts while I put finishing touches on the book.

Of course, this book also draws upon the many, many conversations I have had with colleagues about food and human-animal relationships. It would be impossible for me to name everyone who deserves some credit. I have found the animal ethics and animal studies community a deeply valuable one to be a part of, and so I here thank the community as a whole, rather than any particular members. Further thanks are owed to Khadija Coxon, at McGill-Queens University Press, who has been supportive of this project from its early days, and two anonymous reviewers, who offered extremely valuable feedback.

I would also like to thank my fiance Becky Gray who followed me from Lancaster to Belfast, Belfast to Kingston, and Kingston to York. She is someone who gets easily as much joy from feeding animals as I do. And thanks, too, to the various animal neighbours who have accepted my hospitality; Hollie, my excitable plant-based dog; and the assorted sanctuary animals who have helped me think about different ways we could live together.

Just Fodder

Introduction

Animals, Food, Philosophy

Lots of vegetarians and vegans keep dogs, cats, or other companion animals. But when it comes to the feeding of these animals, they face a dilemma. The received wisdom is that responsible guardians feed dogs and cats a meaty diet. But vegetarians and vegans, at least if theyre vegetarian and vegan for ethical reasons, will hesitate. Animals perhaps animals not so different from their beloved companions suffer and die to produce meat. And vegetarians and vegans think this is a problem; its such a problem for them that they no longer want to support it with their diet. If its wrong to support the meat industry to feed ourselves, is it perhaps wrong to support the meat industry to feed our companions? And what of the animals our companions might eat if left to roam? What guardian of a free-roaming cat doesnt have a story of waking up to gifts of dead or dying animals? These animals, too, matter. The suffering and death that our companions impose on them, on the face of it, raise ethical questions.

But the ethical dilemmas raised by thinking about animals as eaters dont end with companions. Lots of us feed garden wildlife, like the birds for whom we leave nuts and seeds. Lots of us desperately avoid feeding garden wildlife, like the rodents and raccoons who would help themselves to our stores or bins if given half a chance. And the questions raised are far from a purely personal affair. Collectively, through our choices, some animals are encouraged, some are discouraged. The pigeons of Trafalgar Square are brought in by tourists feeding them; the banning of feeding, though perhaps welcomed by those who have no love for the birds, leaves pigeon stomachs empty. The growing of crops attracts farmland animals who would eat those crops; harvest puts these animals in mortal peril, apparently leaving (metaphorical) blood on the hands of almost all of us. Anthropogenic climate change leaves some wild animals, who may never have even encountered humans, hungry; activists call for them to be fed, or launch initiatives to feed them, while others say we should let nature be.

This is a book about these and other practical dilemmas raised when we think about animals and food. The feeding of animals raises a host of normative puzzles. Who are we obliged to feed? Who are we permitted to feed? What are we allowed to feed to animals? What is the role of the state in feeding animals? How might obligations concerning the feeding of animals differ from obligations concerning the feeding of humans, and why? Regrettably, there has been a distinct absence of consideration of these questions in philosophical discourse. This is despite the fact that the questions deal with pressing real-world moral and political problems; these are questions with which individuals, collectives, and legislatures regularly grapple. Individual vegans and vegetarians worry about the ethics of feeding meat to their companions, while householders fear that their love of feeding birds may be putting the birds at risk. Almost anyone who has ever come across a free-living (wild) animal in need has asked whether she should feed this animal. States, meanwhile, are obliged to come up with public health policies concerning human-animal interaction, and laws surrounding the marketing and manufacture of feed. Others grapple with questions in a professional capacity; volunteers or employees at animal shelters and sanctuaries, for instance, must answer questions about feeding on a day-to-day basis.