2011 Gale, Cengage Learning

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced, transmitted, stored, or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including but not limited to photocopying, recording, scanning, digitizing, taping, Web distribution, information networks, or information storage and retrieval systems, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyrighted material.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Sharp, Anne Wallace.

Ice hockey / by Anne Wallace Sharp.

p. cm. (The science behind sports)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4205-0281-7 (hardcover)

1. HockeyJuvenile literature. 2. Sports sciencesJuvenile literature. I. Title.

GV847.25.S43 2010

796.962dc22

2010025670

Lucent Books

27500 Drake Rd

Farmington Hills Ml 48331

ISBN-13: 978-1-4205-0281-7

ISBN-10: 1-4205-0281-6

Printed in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 14 13 12 11 10

TABLE OF CONTENTS

O n March 21, 1970, Slovenian ski jumper Vinko Bogataj took a terrible fall while competing at the Ski-flying World Championships in Oberstdorf, West Germany. Bogatajs pinwheeling crash was caught on tape by an ABC Wide World of Sports film crew and eventually became synonymous with the agony of defeat in competitive sporting. While many viewers were transfixed by the severity of Bogatajs accident, most were not aware of the biomechanical and environmental elements behind the skiers fallheavy snow and wind conditions that made the ramp too fast and Bogatajs inability to maintain his center of gravity and slow himself down. Bogatajs accident illustrates that, no matter how mentally and physically prepared an athlete may be, scientific principlessuch as momentum, gravity, friction, and aerodynamicsalways have an impact on performance.

Lucent Books Science Behind Sports series explores these and many more scientific principles behind some of the most popular team and individual sports, including baseball, hockey, gymnastics, wrestling, swimming, and skiing. Each volume in the series focuses on one sport or group of related sports. The volumes open with a brief look at the featured sports origins, history and changes, then move on to cover the biomechanics and physiology of playing, related health and medical concerns, and the causes and treatment of sports-related injuries.

In addition to learning about the arc behind a curve ball, the impact of centripetal force on a figure skater, or how water buoyancy helps swimmers, Science Behind Sports readers will also learn how exercise, training, warming up, and diet and nutrition directly relate to peak performance and enjoyment of the sport. Volumes may also cover why certain sports are popular, how sports function in the business world, and which hot sporting issuessports doping and cheating, for exampleare in the news.

Basic physical science concepts, such as acceleration, kinetics, torque, and velocity, are explained in an engaging and accessible manner. The full-color text is augmented by fact boxes, sidebars, photos, and detailed diagrams, charts and graphs. In addition, a subject-specific glossary, bibliography and index provide further tools for researching the sports and concepts discussed throughout Science Behind Sports.

A Lightning Fast Game: The Story of Ice Hockey

I ce hockey is a game of lightning-fast action that is both thrilling to watch and to play. With players skating as fast as 30 miles per hour (48kmh) and the puck traveling at speeds up to 100 miles per hour (161kmh), hockey is also the fastest professional contact sport played today.

The game of ice hockey has been described by the Society for International Hockey Research as a game played on the ice rink in which opposing teams of skaters, using curved sticks, try to drive a small disc, ball, or puck into or through the oppositions goal. Players must be proficient in skating, shooting, passing, checking or blocking other players, and stopping the puck. They must also have a high level of endurance and be in peak physical condition to play one of the most demanding games in sports.

The game of ice hockey has been around for hundreds of years. Historians believe that the modern game of ice hockey derives from various ball-and-stick games played throughout the world by indigenous people. The ancient Egyptians and the Mayans of Central America, for instance, both played such games on courts made specifically for the sport. It is believed that these games were the forerunners of many of todays sports.

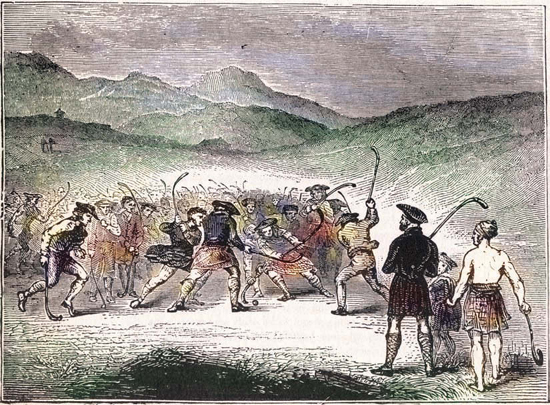

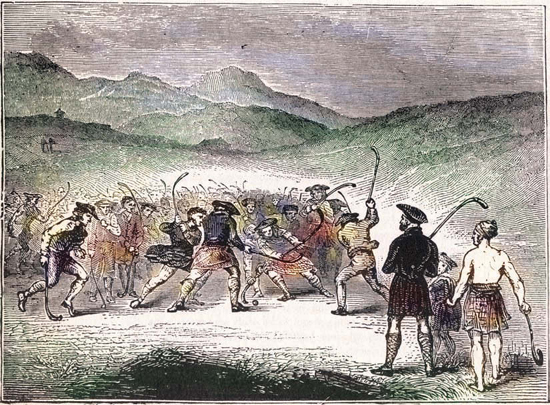

The Scottish game shinty and other early ball-and-stick games helped develop the modern game of ice hockey.

In 1997, during an excavation for a golf course in Colorado, builders found further proof of the early origins of ball-and-stick games. Journalist Alisha Jeter describes a sculpture that was uncovered: The piece depicts five lifesize Cheyenne Indians engaged in the ancient game of shinny in which a ball is hit on a field. Golf, field hockey, lacrosse, and ice hockey all have their origins in these early sports contests.

These ball-and-stick games have been played all over the world, and in many cases, are still being played today. The early Scots, for instance, called their game shinny, or shinty, a popular game played using any kind of stick the players could find. The game could be played anywhere there was a large enough field. Shinny remains a popular sport today and can be played either on ice or on any surface large enough for the players to compete.

Early Forms of Hockey

Archaeological findings suggest that groups of native people in the northern areas of the world were playing a ball-and-stick game on the ice many centuries ago. These games were played using bent sticks and a painted or curved wooden ball. The object was to hit the ball through the opposing teams goal. Ten men played on each team. The Micmac tribe of eastern Canada, for instance, called their game tooadijik. Other names for the game were used by indigenous people in other lands.

The English and Russians played a similar game called bandy as early as the tenth and eleventh centuries. This game originated as a form of field hockey played on ice. It was especially popular in Russia because of the long winters there. Bandy was played using a stick and ball. Two teams of eleven players competed to get the ball into the other teams goal. Today bandy is still a very popular sport, and it is played in the United States and throughout the world.

A game called hurley was played in Great Britain, Ireland, and France as far back as the sixteenth century. It was played in the winter, when the fields were frozen. Players used a ball that was hit with some kind of wooden club. Players strapped blades made of wood or bone onto their shoes to help propel them across the freezing tundra. By the seventeenth century, almost every European country with a cold climate played some form of the game.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the Dutch developed a primitive but more practical form of ice skates by strapping metal blades onto their shoes. The blades allowed the skaters to perform with more balance and speed. They gave the players better traction on the ice, and the blades were also less likely to come loose and cause falls. Ice hockey increased in popularity as a result of the new skates.

Next page