June Kikuchi, Editorial Director

Jarelle S. Stein, Editor

Karen Julian, Publishing Coordinator

Tracy Burns, Jessica Jaensch, Production Coordinators

Indexed by Melody Englund

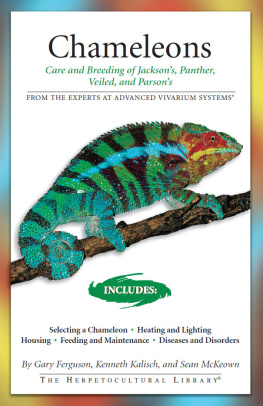

Front cover photo by Bill Love. Back cover photo by Paul Freed. The additional photos in this book are by David Northcott, pp. 5, 113, 121, 113; Bill Love, 9, 18, 29, 30, 45, 51, 55, 56, 65, 69, 78, 88, 89, 93, 100, 107, 112, 116, 118, 122, 123, 126, 127; Heather Powers, 11; Zig Leszczynski, 12, 19, 20, 22, 37, 82, 85, 97, 99, 103, 105, 120; Sean McKeown, 15,16; Isabella Francais, 21, 27, 91, 101; Paul Freed, 24, 26, 33, 34, 61, 63, 86, 115, 119, 136; Dennis Sheridan, 38, 103, 127; Gary Ferguson, 41, 43, 4849 52, 54, 57, 58, 59, 62, 70, 71, 73, 74, 76; Sally Kuyper, 92; John Tashjian, 95; Jim Bridges and Bob Prince, 108; P. Skoog, 129; P. Choo, 131; Kenneth Kalisch, 132, 135

Copyright 2007 by Advanced Vivarium Systems

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Advanced Vivarium Systems, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

LCCN: 96-183295

ISBN: 1-882770-95-1

ISBN-13: 978-1-882770-95-3

eISBN: 9781620080252

An Imprint of I-5 Press

A Division of I-5 Publishing, LLC

3 Burroughs

Irvine, CA 92618

Printed and bound in China

13 12 11 10 09 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

C hameleons are primarily an African and Madagascan group of highly specialized, arboreal, insectivorous lizards comprising more than 130 described species. All the Madagascan forms that have been studied are egg-layers, whereas some of the African forms, including the Jacksons chameleon, give birth to live young (Glaw and Vences 1994). For much of the twentieth century, chameleons were placed in their own suborder, Rhiptoglossa; however, taxonomists have recently reclassified chameleons. They are now considered to be related to the agamids and iguanids, and they have been placed into their own subfamily within the family Chamaeleonidae (Glaw and Vences 1994; Zug 1993) and most are in the genus Chamaeleo.

Chameleons have been called the masters of camouflage, using various abilities to pass almost unseen through the surrounding environment. They rest motionless or move very slowly and deliberately with a rocking gait so they are not seen by potential predators. Their independently rotating eyes, set like turrets, afford them an unobstructed view of their surroundings in all directions at once, without the need to move their heads or bodies. They are also capable of making their bodies appear more elongated to take on the appearance of a twig or a branch and of laterally flattening their sides to make themselves look like just another leaf on a tree. In addition, these lizards have a highly sophisticated ability to vary their skin pigments to match their surroundings.

The chameleons ability to change colors has functions other than camouflage. Its normal colors and the intensity of its color signal its moods to other chameleons of the species. As an ectotherm, it can absorb heat from the sun on cool mornings. In the early morning, the chameleon is usually dark so as to absorb infrared heat. Its colors lighten as its body absorbs more heat and its body temperature rises. Chameleons are renowned for the rapid speed of their skin color change, which occurs through movement of pigment in the skin cells known as chromatophores.

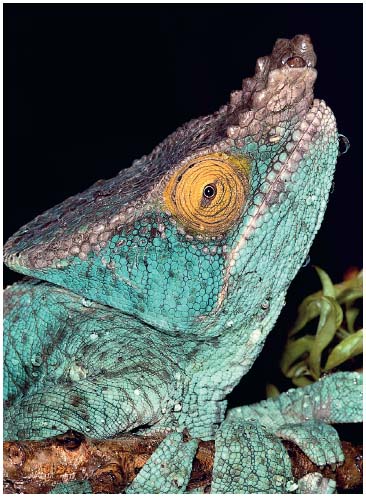

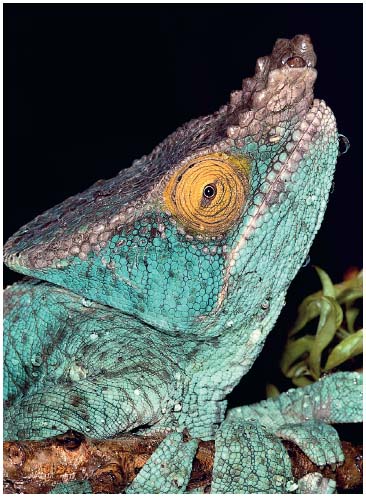

A Parsons chameleon (Calumma parsonii parsonii), one of the four most popular chameleon species, displays its majestic profile. There are some 130 chameleon species.

The chameleons long muscular tongue is a specialized adaptation for arboreal feeding. This lizard can rapidly propel its tongue to as much as one and a half times its body length to capture insect prey. The tip of the tongue is like a moist suction cup that attaches to the prey and rapidly jerks it back into the mouth.

Feet with opposable toes allow the chameleon to grip branches firmly and to move slowly but deliberately between branches to feed or to flee. The long tail is also prehensile. At night, it is curled up while the chameleon sleeps. (If a portion of its tail is lost, the chameleon cannot regenerate it.)

Although chameleons are sometimes considered easy keepers, they have highly specialized needs. While one chameleon species may be appropriate for a relatively inexperienced keeper, others are only for experts. Understanding each species habitat and natural history can greatly extend chameleons lives in captivity. The intention of this book is to help new and experienced herpers provide the best care possible for their chameleons.

In this book, we will take a look at the four most commonly kept chameleon species: Jacksons chameleon (Chamaeleo jacksonii), panther chameleon (Furcifer pardalis), the veiled chameleon (Chamaeleo calyptratus calyptratus), and Parsons chameleon (Calumma parsonii parsonii). The first three are the most popular and commonly kept because they are the most frequently and easily captive-bred. Captive-bred animals are easier to care for than are wild caughts. These four species also have interesting appearances. Jacksons have triceratops horns on their heads, panthers have awesome colors, veileds have an interesting casque on their heads and are very hardy, and Parsons are quite large for chameleons. These species have contributed to the overall popularity of chameleons in captivity.

PART I

JACKSONS CHAMELEON

(CHAMAELEO JACKSONII)

By Sean McKeown

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION AND NATURAL HISTORY

T here are three currently recognized subspecies of Chamaeleo jacksonii: C. j. jacksonii, C. j. merumontanus, and C. j. xantholophus. Since the original description of the species, there has been considerable confusion about the taxonomy of the subspecies. The Jacksons chameleon (Chamaeleo jacksonii) was originally described in 1896 by the Belgium-born curator of the British Museum of Natural History, G. A. Boulenger. His initial description was based on a partially grown preserved male specimen that had been donated to the museum by F. J. Jackson. The title of the article describing this initial specimen was Description of a New Chameleon from Uganda (Boulenger 1896); however, the actual label on the type specimen clearly indicated that it was collected in the vicinity of Nairobi, in the Kikuyu District of Kenya, in what was then part of British East Africa (Eason, Ferguson, and Hebrard 1988). Several years later, in 1903, J. Tornier described what he called C. j. vauerescecae from Nairobi. Half a century later, in 1959, the Dutch herpetologist Dirk Hillenius invalidated this subspecies as he found individuals of C. j. jacksonii in the general area of their type locality (Nairobi) that clearly fell within the range of Torniers description (Hillenuis 1959). At about the same time, A. Stanley Rand of the Smithsonian Institution described a smaller form, the Mount Meru Jacksons chameleon, C. j. merumontana (Rand 1958). Finally, thirty years later, Perri Eason, Gary W. Ferguson, and James Hebrard undertook field work in East Africa that led to the formal description of a new subspecies, a form already well known to herpetoculturists: the Mount Kenya yellow-crested Jacksons chameleon,

Next page