Ken Doherty, world champion in 1997.

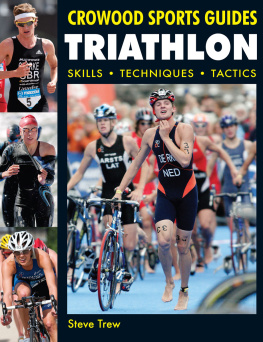

SNOOKER

AND BILLIARDS

Clive Everton

2nd EDITION

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 1991 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2014

www.crowood.com

Revised edition 2014

The Crowood Press Ltd 1991 and 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 793 9

Picture Credits

Line drawings by Compass Design

Photographs by Eric Whitehead, Mark Stephenson and Tai Chengze

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jim Chambers, a former professional snooker player and a respected coach.

Throughout this book the pronouns he, him and his have been used inclusively and are intended to apply to both males and females.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

If you think that you cannot learn anything from books, then consider Steve Davis, who won six world titles in the eighties.

Steve Davis was perhaps not blessed with as much natural ability as Stephen Hendry, Ronnie OSullivan, Judd Trump or Jimmy White, all of whom seem to have been born with a cue in their hand. Instead, he manufactured himself into the great player he became.

In his teens, his bible was a book by Joe Davis, who won every world title on offer from 1927 to 1946. The book is long since out of print and some of its confident coaching assertions, accepted for years, have been superseded, but Steve derived an enormous amount of benefit from it, poring over it as he tried to acquire the technique which is the irreplaceable foundation of performance.

Instructional books have two functions: to tell you something you didnt know, or to remind you of something you may have forgotten or are no longer putting into practice. You wont improve simply by reading a book, but you might if you take up on the practice table the material within it. Many have.

Good luck, and keep your chin down.

Clive Everton

About the Author

Clive Everton was five times Welsh amateur billiards champion, five times runner-up in the English Amateur Championship, and twice a World Amateur Championship semi-finalist. His professional career was blighted by back and knee surgery, although he nevertheless reached ninth place in the billiards world rankings. A Welsh amateur snooker international, twice a Welsh Amateur Championship semi-finalist and once an English Amateur Championship semi-finalist, his highest professional snooker ranking was 48th.

Best known as a television commentator, he is the author of numerous books, including A History of Billiards and Black Farce and Cue Ball Wizards, the inside story of the snooker world, which was shortlisted in the British Sports Books of the Year awards. He has been editor of Snooker Scene, the games monthly magazine, since 1971.

Judd Trump.

PART 1

INTRODUCTION TO THE GAME

Ronnie 'The Rocket' O'Sullivan, five times world snooker champion.

CHAPTER 1

HISTORY

Billiards was the father of all billiard table games, but before snooker came to be played, there already existed a number of other potting games. Pyramids was played with the triangle of fifteen reds (with the apex red on what is now the pink spot) but no colours. It could be played by two or more players with an agreed stake per ball, or simply by two players the first to pot eight reds being declared the winner.

A number of early pool games, so-called because the players were required to pool their bets in a kitty prior to commencement of play, also lent themselves to a flutter. Black Pool, for instance, was played, like Pyramids, with fifteen reds but also with the black placed either on the middle spot or on what is now the black spot. This was then known as the billiard spot, i.e. the spot on which the red was placed in billiards. Anyone who potted the black extracted additional winnings from his opponents.

In Life Pool, each player adopted a different coloured ball and lost a life (or monetary forfeit) when it was potted by an opponent. A player losing three lives was dead, and the last player left alive scooped the pool.

These were all popular games in 1875, not only in Britain but wherever there was a strong British influence. In the long, hot summer of that year, in the Nilgiri Hills in southern India, Field Marshal Sir Neville Bowles Chamberlain, then a nineteenyear-old junior officer, became aware of the boredom of the army officers who spent most of their days at the Ooty Club, Ootacamund. To relieve this, he decided to merge the elements of some of these existing games into a new game, which came to be known as snooker.

The name snooker originated from army slang. A snooker (meaning the lowest of the low) was an expression attached to first-year cadets at the Royal Military College, Woolwich. Snook was also a derogatory Indian expression. When, therefore, whether by accident or design, a player so positioned the cue ball that his opponent could not strike the ball on, he came to be referred to as a snooker. From this came the verb to snooker, and hence the name of the game itself.

Chamberlains original idea did not leave India until 1885 when John Roberts (junior) not only the greatest player, but also the greatest entrepreneur of his day met Chamberlain in Bangalore and brought the idea back to England. There, the John Roberts Billiard Supply Co. began to commercialize the game with sales of snooker sets, which of course consisted of twenty-two balls and cost considerably more than a three-ball billiards set.

In contrast to billiards, in which good players could keep their opponents sitting out for long periods, snooker became popular as a more sociable type of game. Professionals were contemptuous of it, but the game gained enough support among amateurs for the English Amateur Championship to be instituted in 1916. A professional championship followed in 1927 through the personal initiative of Joe Davis, who duly won it and retained it until he retired from World Championship play in 1946, but snooker remained the poor relation to the Professional Billiards Championship until the mid-1930s.

The financial return rose gradually from the 6 10s which Davis netted from his 1927 success, and standards of play improved. In the early days, the general idea was to pot what was obviously on and then play safe, but Davis himself was already evolving the sophisticated breakbuilding techniques which now form part of the armoury of all leading players, and the tactical side of the game progressively developed its present complexity.

Fred Davis started to emerge as a threat to his elder brother, and in fact only lost the 1940 world final 3736. Horace Lindrum also ran the champion reasonably close, 7867, in 1946, the first world final from which the participants made any real money.