Page List

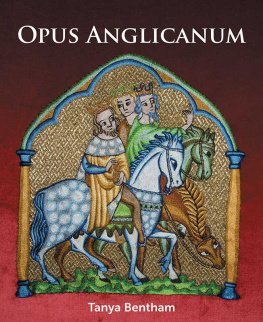

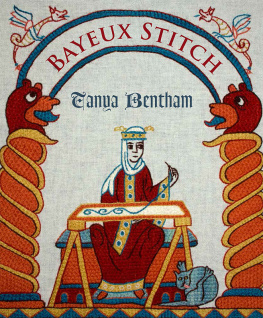

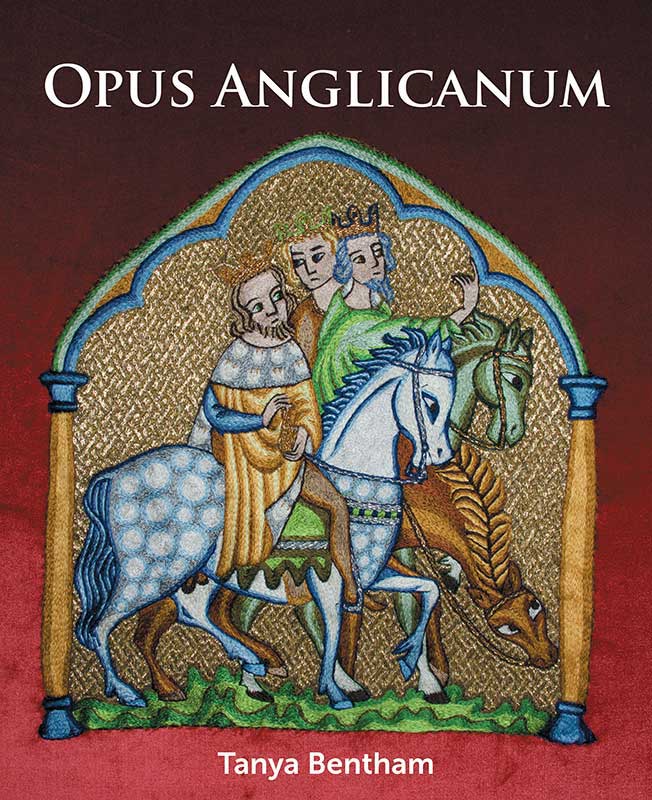

OPUS ANGLICANUM

OPUS ANGLICANUM

A practical guide

Tanya Bentham

First published in 2021 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

Tanya Bentham 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 897 9

Cover design: Peggy & Co Design

Photography: Dr G Davies

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Brenda Scarman, Mary Frost, Anna Novitsky, Amanda Ashton, Liz Elliot, Kathleen Griffiths, Dr Timothy Dawson, Hazel Johnson and Bess Chilver for their input to this book.

INTRODUCTION

E ssentially, opus anglicanum uses just two stitches split stitch and underside couching so it must be pretty straightforward, right?

Not really.

Opus anglicanum is as much an artistic style as it is a form of needlework. It is a style that affects everything, from the choice of the original inspiration that forms the basis of your design, to the selection of materials, right down to the placement of each individual stitch.

It is slow, too, so, if you need a quick fix, go to do some cross stitch; if you want to get your teeth into something, try opus.

Even in its secular forms, all medieval art addresses the divine, and opus anglicanum is no exception. It plays with light in much the same way as the great Gothic cathedrals do, by manipulating the light to create something that is more than the mere sum of its parts. The reflection of light on the filament silk and gold threads that are used for working opus anglicanum is as important as the stitches themselves, and I hope to show you how to play with light, as well as how to perform two very simple stitches.

It is not my intention to provide a history of the technique, but inevitably history will be mentioned, because it affects the design choices made throughout this book. The book will deal only with the early period of opus before the Black Death changed the technique into a more debased style and faster form of needlework.

This is a guide for getting on with things, and, if you start at the very beginning, you can use it as a complete course for a beginner, or you can dip in and out of it if you already feel more confident as an embroiderer. Every project is chosen to showcase at least one new variation of the basic technique, with each project increasing in difficulty throughout the book.

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1

MATERIALS, TOOLS AND FRAMES

FABRIC

The fabric that I have used throughout this book for the examples and projects is a fine ramie canvas. Ramie is a plant fibre similar to linen, and the two corresponding fabrics would often be lumped together historically. I use ramie because it is finer than any linen that I have been able to find in repeatable quality. It is about 80 count, and I use two layers, which I usually machine-stitch together around the edges of the pieces before attaching the seamed, double-layer fabric on to the frame.

When working opus, you make a lot of holes in the canvas, so, the finer its count, the less these holes show. The results of opus are best if you never split the individual threads of the canvas, so, the finer the canvas is, the less chance there is of it being damaged.

Where a coloured canvas is used, I have used a twill silk similar to that seen for historical examples, backed with two layers of my usual ramie.

THREADS

For opus anglicanum, it is essential to use silk threads and in particular filament-silk threads for working split stitch, which forms the majority of the stitching of an embroidered piece. There are exceptions to this, for example, when working couching with metal or metal-effect threads, and linen thread is also needed for couching. Cotton threads should not be used, as explained further in .

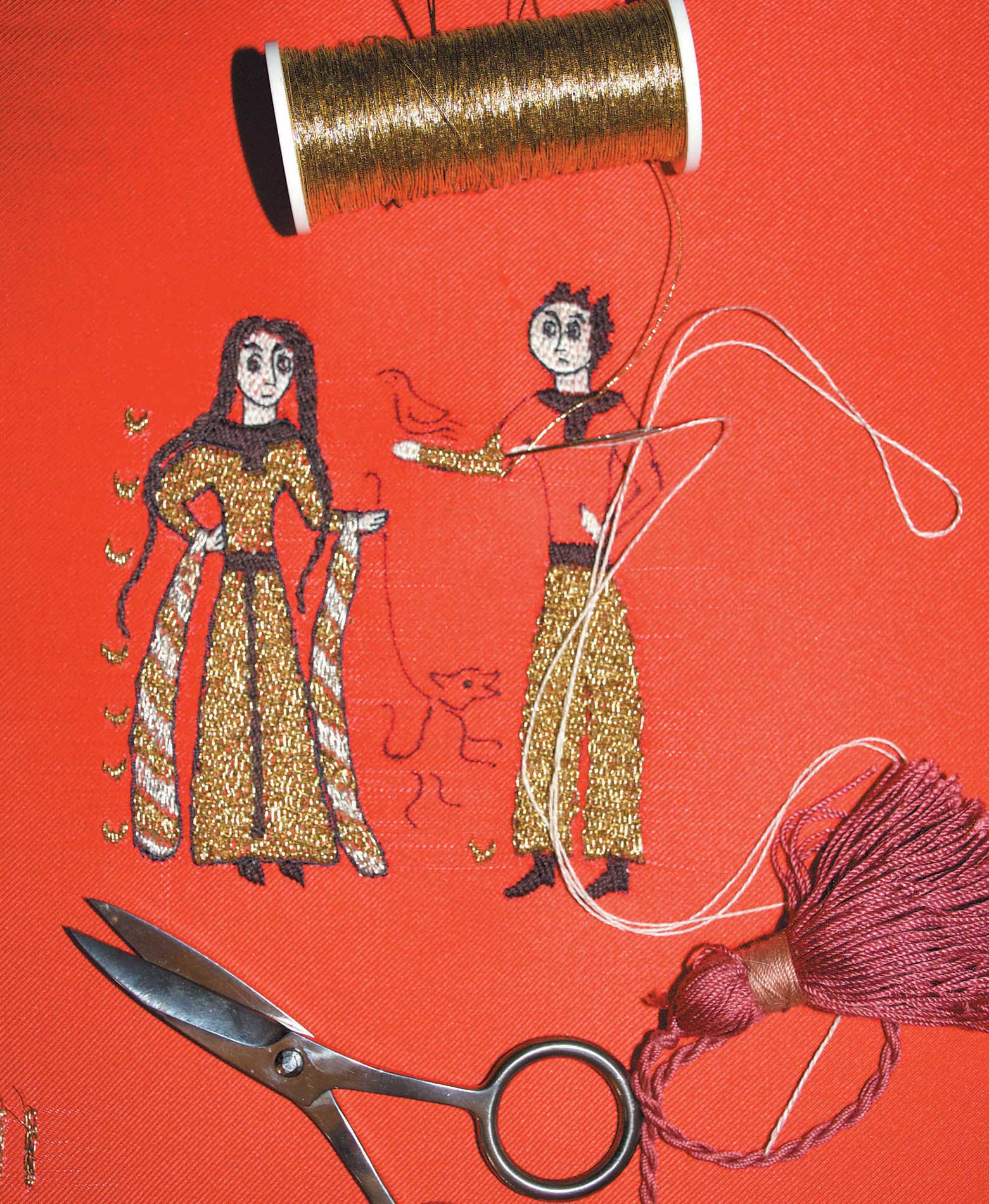

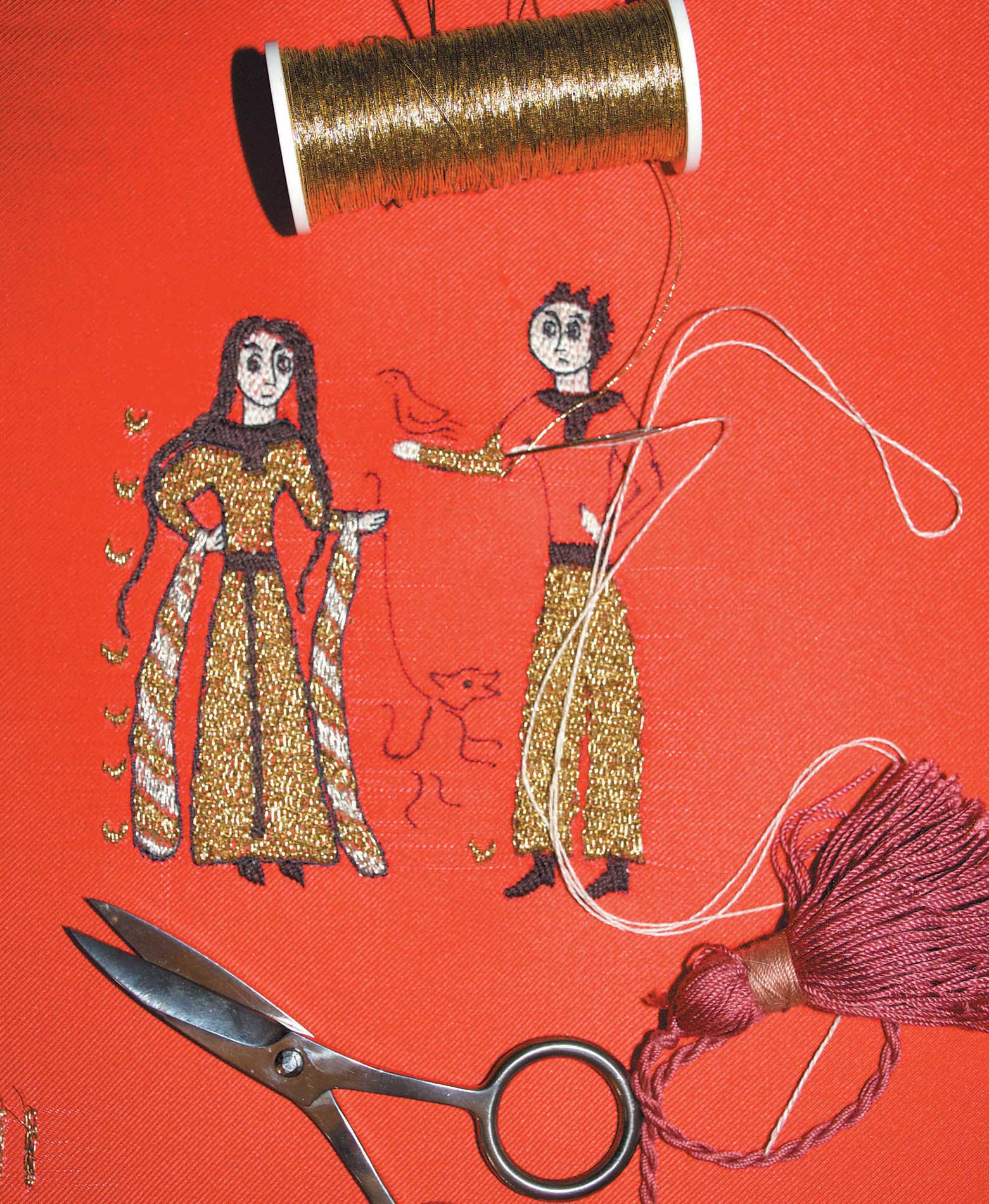

This is a close-up of a single layer of the ramie fabric used for the examples and projects throughout this book. The translucency of this fabric is apparent.

We will explore the characteristics and uses of various silk thread types and other thread types in and subsequent chapters.

TOOLS

I dont use many fancy tools and materials: the following items are about all that I need, in addition to the silk thread for stitching and the fabric upon which to stitch.

These are the main tools that I need for working opus (from left to right): good linen thread; beeswax, for conditioning the linen thread; a stiletto, for making holes in things, especially the canvas, and for poking; small scissors (I dont buy expensive ones, just lots of pairs of brightly coloured, cheap ones); and a permanent fabric-marking pen.

Some people like to use a magnifier when working opus, but, to be honest, I find that a good light source is of more use. Get something bright that can be directed to where you need to see.

Transferring designs

The ramie that I use is quite translucent: if you photocopy your design and hold it against the back of the fabric (prop this fabricphotocopy sandwich up against the pages of a thick book or two, so that the fabric is pressed against the design), you can trace the design lines easily. You can get really good A4 LED light boxes quite cheaply, which are great for tracing, and some people insist on taping the design and overlying fabric to a window for tracing. I always prefer to have the fabric laced on to the frame before transferring the design; this way, the canvas cant move around under the pen, and you get a more accurate drawing.

The prick-and-pounce technique is really only practical if you want to work a particular design more than once, or if you have repeated elements, otherwise it is an awful lot of work for something that you want to mark only once. I have always suspected that professional medieval workshops kept a selection of stock designs, and probably complicated shapes like the lobed quatrefoils used in the Syon Cope, marked out on vellum for prick and pounce but that more-bespoke designs were done as a one-off and always drawn freehand.

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1