Shrabani Basu is a journalist and author. Her books include

For King and Another Country, Indian Soldiers on the Western Front 191418, Victoria & Abdul, The True Story of the Queens Closest Confidant, Spy Princess, The Life of Noor Inayat Khan and Curry: the Story of Britains Favourite Dish. She has edited

Reimagine: IndiaUK Cultural Relations in the Twenty-First Century. She writes regularly for the Indian newspapers

ABP and the

Telegraph and has contributed to the

Daily Express, Mail on Sunday and other publications. She is founder and chair of the Noor Inayat Khan Memorial Trust. Lee Hall was born in Newcastle in 1966.

He started writing for radio in 1995, winning awards for I Luv You Jimmy Spud, Spoonface Steinberg and Blood Sugar, all of which made the journey to other media. His screenplay for Billy Elliot was nominated for an Oscar and was adapted into the multi-award-winning stage musical. The Pitmen Painters received the Evening Standard Best Play Award and TMA Best New Play Award. Our Ladies of Perpetual Succour premiered at the Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh, in 2015 and transferred to the National Theatre, London, the following year. The play won the Olivier Award for Best New Comedy and transferred to the Duke of Yorks, London, in 2017. He has worked as writer-in-residence for Live Theatre, Newcastle, and the Royal Shakespeare Company, and has adapted many plays for the stage, including Goldonis A Servant to Two Masters (Young Vic/RSC), Brechts Mr Puntila and His Man Matti (Right Size/Almeida) and Heijermans The Good Hope (National).

BILLY ELLIOT: THE SCREENPLAY

THE PITMEN PAINTERS

OUR LADIES OF PERPETUAL SUCCOUR

SHAKESPEARE IN LOVE (based on the screenplay by Marc Norman and Tom Stoppard) published by BBC Books SPOONFACE STEINBERG AND OTHER PLAYS published by Methuen PLAYS: ONE

PLAYS: TWO

THE ADVENTURES OF PINOCCHIO

COOKING WITH ELVIS & BOLLOCKS

THE GOOD HOPE

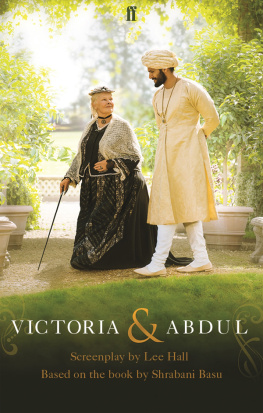

A SERVANT TO TWO MASTERS Lee Hall Based on the book VICTORIA & ABDUL: THE TRUE STORY

OF THE QUEENS CLOSEST CONFIDANT by Shrabani Basu

CONTENTS

First published in the UK in 2017

by Faber & Faber Ltd

Bloomsbury House

7477 Great Russell Street

London WC1B 3DA This ebook edition first published in 2017 All rights reserved

Cross Street Films (Trading) Limited, 2017 Cover design by Faber

Image credits 2017 Focus Features LLC All rights reserved. The rights of Lee Hall to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights whatsoever in this work are strictly reserved. Applications for permissions for any use whatsoever, including performance and/or music rights must be made in advance, prior to any such propsed use to Judy Daish, Associates Limited, 2 St Charles Place, London W10 6EG. No performance may be given unless a licence has first been obtained. This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly ISBN 9780571342235

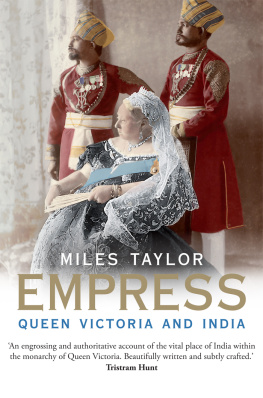

Driving down the Holloway Road in London mindlessly listening to someone on the radio talking about curry, I was jolted out of my reverie when I thought I heard them say that the first person to cook a curry for Queen Victoria, Empress of India, was an Indian Muslim manservant who was also not only her most intimate confidant but her spiritual advisor.

Could I have heard this correctly? An Indian Muslim manservant who had been a common scrivener in an Agra gaol had become the mentor of the most powerful person on Earth, teaching her Urdu and the Koran? How was this possible? How come Id not heard of it before? I leapt out of the car and listened to the whole thing again on iPlayer, not quite believing my ears. I rather incredulously told the story to my wife, the film-maker Beeban Kidron, and a couple of days later we were sitting with Shrabani Basu, the person Id heard on the radio, who had just finished writing a book about it all. Shrabani had been researching the history of curry when she came across the story of Abduls relationship with Queen Victoria. When the Queen died, Abdul became persona non grata and was exiled from Britain. All documentary evidence of his relationship with the Queen was burned, including her thousands of letters to him. But following the story back to Agra where the unfortunate Abdul was finally forced to retreat, Shrabani discovered a number of his private journals, which hed smuggled out of Britain.

Her discovery of Abduls own writings, long thought to have been lost, gave unprecedented access to the story. Beeban persuaded Shrabani to entrust the resulting book to us, and I went off to write a script. The story is rich in so many ways: the outsider who upsets the order of things, the dying monarch, the dying Empire. But what amazed me most was that Victoria herself stood up against the profound racism and condescension of the household and her family, and championed not only the man but his religious beliefs. The fear of Islam that blights us now was no different then, and I quickly recognised this was a story as pertinent today as it ever had been. To be frank, as a convinced republican I knew very little about Victoria, but the more I found out the more fascinated I became.

The ironies and absurdities were just so delicious. The fact that the Queen was made Empress of India after the Mutiny yet could never visit because shed be assassinated astonished me. The descriptions of the gargantuan meals she was expected to consume were equally amazing. Almost everybody who came into close contact with her wrote a memoir at some point and reports of her indecorous table manners made me laugh out loud. I realised the whole thing was grand comedy. Abdul was pilloried in almost all contemporary commentaries for being some kind of usurper: a self-interested Svengali out to dupe the Queen.

But it was clear to me that the Queen was no fool and the story becomes much more interesting when you take Abdul as seriously as Victoria did. Far from being an Indian Tartuffe, Abdul seemed more like an innocent abroad. If anything he was an Uncle Tom who received rather rough justice for misjudging the institutional racism and malevolence at the core of the Empire. Yet at the heart of it all is a love story between an eighty-year-old woman who happened to be the richest and most powerful person on earth and a young Indian nobody. It seemed to speak about all the contradictions of power. When one examined it carefully it became less and less clear who was the master and who the slave.

Ultimately India gained independence and, certainly in my version of events, the Queen receives some liberatory transcendence because of Abduls good offices. So although this is in part a sad tale of racism and an indictment of empire it is also, potentially, a hopeful one where simple kindness and love can disrupt some of that manifest iniquity. Beeban introduced me to Stephen Frears, whose beady eye for the preposterousness of any convention and his generally wicked sense of irony was a perfect match for my subaltern take on the pretensions of empire. He immediately announced that the film was impossible to make without Judi Dench, which rather put the kibosh on everything as Judi had already played Queen Vic and is famously disinclined to revisit old roles. Undeterred Stephen went off to visit Judi and came back with the news that shed read the script and was officially on board. Judi is every writers dream.