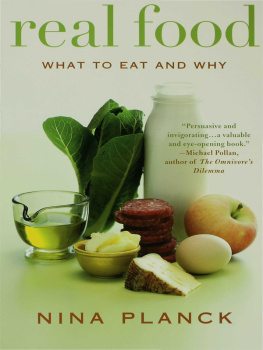

real food

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Farmers'Market Cookbook

real food

WHAT TO EAT AND WHY

NINA PLANCK

BLOOMSBURY

Copyright 2006 by Nina Planck

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bloomsbury USA, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, New York Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

The ideas and suggestions in this book are not intended to replace the services of a health professional. The reader is advised to take professional advice before making significant changes in diet.

All papers used by Bloomsbury USA are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE HARDCOVER EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Planck, Nina, 1971- Real food: what to eat and why / Nina Planck.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN-13: 978-1-59691-144-4 (hardcover) ISBN-10: 1-59691-144-1 (hardcover) 1. Nutrition United States. 2. Diet United States. I. Title.

TX360.U6P63 2006

613.20973 dc22

2005033624

First published in the United States by Bloomsbury in 2006 This paperback edition published 2007

Paperback eISBN: 978-1-59691-342-4

10 9 8 7 6 5 4

Typeset by Palimpsest Book Production Ltd, Grangemouth, Stirlingshire Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor World Fairfield

Contents

WHEN I WAS GROWING UP on a vegetable farm in Loudoun County, Virginia, we ate what I now think of as real food. Just about everything at our table was local, seasonal, and homemade. Eating our own fresh vegetables certainly made me proud; they tasted better than the supermarket vegetables other people ate. But I regarded homemade granola, whole wheat bread, and chicken livers not to mention the notable lack of store-bought processed foods in brightly colored boxes in our kitchen as uncool. Today, my embarrassment over the simple American meals we ate is long gone, and I regard the food I grew up on as the very best. It's true that in certain quarters these days, sauted chicken livers are fashionable, but I don't care about that; I prefer real food because it's delicious and it's healthy.

What is real food} My rough definition has two parts. First, real foods are old. These are foods we've been eating for a long time in the case of meat, fish, and eggs, for millions of years. Some real foods, such as butter, are more recent. It's not absolutely clear when regular dairy farming began, but we've been eating butterfat for at least ten thousand years, perhaps as many as forty thousand. By contrast, margarine hydrogenated vegetable oil made solid and dyed yellow to resemble traditional butter is a modern invention, merely a century old. Margarine is not a real food.

Consider the soybean. Asians have been eating foods made from fermented soybeans, such as miso, tofu, and soy sauce, for about five thousand years. Without fermentation, the soybean isn't ideal for human consumption. But most of the modern soy products Americans eat are not traditional soy foods. The main ingredient in modern soy foods and many processed foods, such as low-carbohydrate snack bars, is "isolated soy protein," a by-product of the industrial soybean oil industry. This unfermented, defatted soy protein is not real food.

Second, real foods are traditional. To me, traditional means "the way we used to eat them." That means different things for different ingredients: fruits and vegetables are best when they're local and seasonal; grains should be whole; fats and oils unrefined. From the farm to the factory to the kitchen, real food is produced and prepared the old-fashioned way but not out of mere nostalgia. In each of these examples of real food, the traditional method of farming, processing, preparing, and cooking enhances nutrition and flavor, while the industrial method diminishes both.

Real beef is raised on grass (not soybeans) and aged properly.

Real milk is grass-fed, raw, and unhomogenized, with the cream on top.

Real eggs come from hens that eat grass, grubs, and bugs not "vegetarian" hens.

Real lard is never hydrogenated, as industrial lard is.

Real olive oil is cold-pressed, leaving vitamin E and antioxidants intact.

Real tofu is made from fermented soybeans, which are more digestible.

Real bread is made with yeast and allowed to rise, a form of fermentation.

Real grits are stone-ground from whole corn and soaked with soda before cooking.

Industrial food is the opposite of real food. Real food is old and traditional, while industrial food is recent and synthetic. The impersonation of real food by industrial food, by the way, is neither accidental nor hidden. Industrial food like margarine is intended to be a replica of a traditional food butter. Real food is fundamentally conservative; it doesn't change, while industrial food, by contrast, is under great pressure to be novel. The food industry is highly competitive and relentlessly innovative, producing thousands of new food products every year. Most of these "new" foods are merely new combinations of old ingredients dressed in a new shape (individually wrapped cheese slices instead of the traditional wheel of pressed cheese) or new packaging (whipped cream in an aerosol can). Or the new recipe has been tweaked to ride the latest food craze (cholesterol-free cheese, low-carbohydrate bagels). Real food, on the other hand, doesn't change because it doesn't have to. My morning yogurt is a masterfully simple recipe for cultured milk, passed down for thousands of years.

So that's my custom definition of real food: it's old, and it's traditional. To lexicographers, sticklers, and nitpickers (you know who you are), it's no doubt hopelessly imprecise and incomplete, but I hope it's clear enough for our purposes.

People everywhere love traditional foods. They're fond of a nice steak, the crispy skin of roast chicken, or mashed potatoes made with plenty of milk and butter. But they're afraid that eating these things might make them fat or, worse, give them a heart attack. So they do as they're told by the experts: they drink skim milk and order egg white omelets. Their favorite foods become a guilty pleasure. I believe the experts are wrong; the real culprits in heart disease are not traditional foods but industrial ones, such as margarine, powdered eggs, refined corn oil, and sugar. Real food is good for you.

Does that mean you should enjoy real bacon and butter not because they're tasty but because they're actually healthy} In a word, yes. Some might mock this as a characteristically American case for real food call it the Virtue Defense. Gina Mallet, an Anglo-American "food explorer" who defends real foods, including beef and raw milk cheese, in Last Chance to Eat: The Fate of Taste in a Fast FoodWorld, calls the modish philosophy healthism and her intent is not to flatter. As scientists began to blame the diseases of civilization on diet, Mallet writes, "a new philosophy emerged, based on the notion that death could be delayed, perhaps even cheated, if a person monitored every single piece of food she ate." I'm concerned about nutrition, but I wouldn't call myself a healthist. For one thing, living forever doesn't interest me, and for another, flavor does.

Someone else a French chef perhaps might take a different approach in defense of real food. Less interested in health, he might champion pleasure for its own sake. Great I'm all for pleasure. If the sheer sensual joy of eating shirred eggs or homemade ice cream is enough for you to shed your guilt, throw away phony industrial foods, and return to eating real foods, all the better. I'll leave the nature of taste and satisfaction, guilt and pleasure to the cultural critics and moral philosophers.

Next page