HIDES & SKINS

AND THE

MANUFACTURE OF LEATHER

A LAYMANS VIEW

OF THE INDUSTRY

BY

JAMES PAUL WARBURG

Assistant Cashier

The First National Bank of Boston

Copyright 2013 Read Books Ltd.

This book is copyright and may not be reproduced or copied in any way without the express permission of the publisher in writing

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Leather Crafting

Leather is a durable and flexible material created by the tanning of animal rawhide and skin, often catde hide. It can be produced through manufacturing processes ranging from cottage industry to heavy industry, and has formed a central part of the dress and useful accessories of many cultures around the world. Leather has played an important role in the development of civilisation from prehistoric times to the present, and people have used the skins of animals to satisfy fundamental (as well as not so essential!) needs such as clothing, shelter, carpets and even decorative attire. As a result of this importance, decorating leather has become a large past time. Leather crafting or simply leathercraft is the practice of making leather into craft objects or works of art, using shaping techniques, colouring techniques or both. Today, it is a global past time.

Some of the main techniques of leather crafting include:

Dyeing - which usually involves the use of spirit- or alcohol-based dyes where alcohol quickly gets absorbed into moistened leather, carrying the pigment deep into the surface. 'Hi-liters' and 'Antiquing' stains can be used to add more definition to patterns. These have pigments that will break away from the higher points of a tooled piece and so pooling in the background areas give nice contrasts. This leaves parts unstained and also provides a type of contrast.

Painting - This differs from leather dyeing, in that paint remains only on the surface whilst dyes are absorbed into the leather. Due to this difference, leather painting techniques are generally not used on items that can or must bend, nor on items that receive friction, such as belts and wallets - as under these conditions, the paint is likely to crack and flake off. However, latex paints can be used to paint flexible leather items. In the main though, a flat piece of leather, backed with a stiff board is ideal and common, though three-dimensional forms are possible so long as the painted surface remains secured. Unlike photographs, leather paintings are displayed without a glass cover, to prevent mould.

Stamping - Leather stamping involves the use of shaped implements (stamps) to create an imprint onto a leather surface, often by striking the stamps with a mallet. Commercial stamps are available in various designs, typically geometric or representative of animals. Most stamping is performed on vegetable tanned leather that has been dampened with water, as the water makes the leather softer and able to be compressed with the design. After the leather has been stamped, the design stays on the leather as it dries out, but it can fade if the leather becomes wet and is flexed. To make the impressions last longer, the leather is conditioned with oils and fats to make it waterproof and prevent the fibres from deforming.

Molding and shaping - Leather shaping or molding consists of soaking a piece of leather in hot or room temperature water to greatly increase pliability and then shaping it by hand or with the use of objects or even molds as forms. As the leather dries it stiffens and holds its shape. Carving and stamping may be done prior to molding. Dying however, must take place after molding, as the water soak will remove much of the colour. This mode of leather crafting has become incredibly popular among hobbyists whose crafts are related to fantasy, goth / steampunk culture and cosplay.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

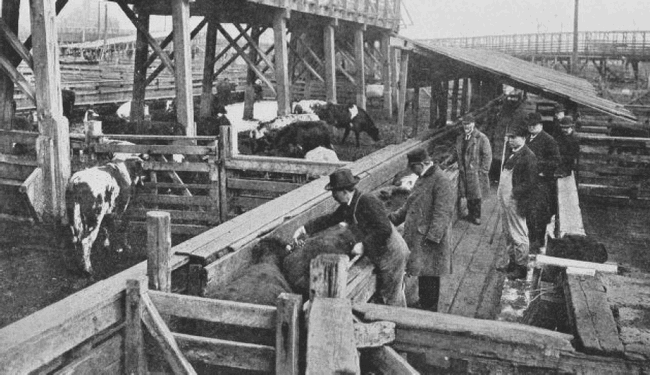

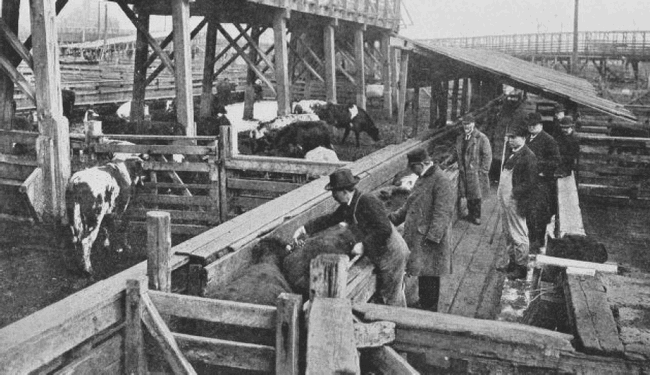

FRONTISPIECE

Inspection of Cattle before Killing

FOREWORD

THE EVOLUTION OF THE INDUSTRY

Probably every man who has ever seen leather knows it to be derived from the skin of various animals; but probably not one in ten even thinks that he understands just what has happened to the raw skin to make it leather; and, as a matter of fact, scientists are to this day divided in their opinions as to whether the change caused by tanning is chemical, or physical, or both. The twofold object of all tanning processes is to render the skin imputrescible and more or less elastic. The origin of how this was first accomplished cannot be traced, for the attempt to preserve the skins of animals dates back far beyond recorded history into the time of primitive savages. Specimens of ancient Egyptian leather, said to have been manufactured at least a thousand years before the birth of Christ, are still to be seen in a museum in Europe, and it is probable that the inhabitants of the Nile delta at that time were fully as versed in the art of tanning as were our ancestors in the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

We may picture to ourselves an early savage, wearing a dried pelt of some animal as a cloak. We may think of him at first surprised, and then considerably annoyed to find that the softness of the skin entirely disappeared as soon as it was thoroughly dry, giving place to an exceedingly disagreeable horniness. His first reaction would be to soak the skin in water in an attempt to render it once more supple. It was probably in this way that the natives of Japan discovered that the waters of certain streams had a softening and preservative effect upon skins, for they flowed over a bed-rock of alum. Until very recently Japanese white leather was produced in this primitive manner.

Failing such a fortunate freak of nature, our savage would find to his chagrin that as soon as his pelt had dried, it became once more hard, and furthermore began to show signs of decay. We may picture him then trying the effect of animal fats, or perhaps of smoke, or in some way discovering the preservative effect of twigs and pieces of bark. In any one of these ways, provided it were continued long enough, he might obtain a rudimentary tannage. To be sure, he would be far from producing a leather that could be made into a modern shoe, but nevertheless he would possess a skin practically immune from decay, and softened to a certain degree.

The progress in the development of leather manufacture until mediaeval times was comparatively negligible, and historical data are lacking by which to trace its course. We know, however, that by the end of the sixteenth century the manufacture of curried leather was well established in Hungary, and that Spain was at that time producing a fair quality of morocco. Gradually the industry spread over Europe, America, and other parts of the world; machinery was slowly perfected to take the place of manual operations; new finishes, such as waxed calf and alum-tanned kid, were added to the old Spanish crup and cordovan leathers; and finally, about thirty years ago, scientific chemistry evolved the chroming process, by which it is estimated that ninety per cent, of the worlds upper shoe leather is made to-day.

The remarkable feature of the industry, even now, remains the fact that it rests primarily on an empirical basis, far more so than any other of our primary industries. While it is probably true that medicinal herbs constituted the first chemical discovery of man, it may well be claimed that industrial chemistry, to which our present civilization owes so many of its material adjuncts, originated in the preservation of animal skins.

Besides the usage of leather for boot soles and uppers, there are an infinite number of purposes to which it has been adapted, some of which it will be impossible to treat here in even a cursory manner. It is not intended by these omissions in any way to belittle the importance of the subjects which the author has felt to lie beyond the scope of this pamphlet. Furthermore, in order to avoid duplication, the arbitrary expedient has been adopted of discussing in Part Two only the vegetable tannage of sole leather, and in Part Three only the chrome process for making upper boot leather. In this manner each method of tanning is taken up in detail in the field where it finds its greatest application, but it must not be inferred by the lay reader that sole leather is never chromed, or that no upper leather is made by the vegetable processes. While this fact is brought out later on, it cannot be too strongly emphasized at the outset.

Next page