Observing and

Developing Schematic

Behaviour in Young Children

A Professionals Guide for Supporting

Childrens Learning, Play and Development

Tamsin Grimmer

Jessica Kingsley Publishers

London and Philadelphia

Contents

About the Author

Tamsin Grimmer is an experienced and excellent independent consultant and trainer and one of the directors of Linden Learning. Tamsin is passionate about young childrens learning and development and is fascinated by how very young children think. She believes that all children deserve practitioners who are inspiring, dynamic, reflective and passionate about teaching them and has a keen interest in the different ways that children learn. Tamsin is particularly interested in play, schemas, active learning, promoting positive behaviour and supporting early language development. In her spare time, Tamsin is in her final year of studying for a Masters Degree in Early Childhood Education at the University of Chester.

Introduction

Tuning into childrens interests and fascinations is part of daily practice for those working with or caring for young children. We watch the children as they play, sometimes from a distance as an observer and sometimes while we participate in the play with them. Children are often engaged in play that is repetitive in nature, for example lining up their toys, or they show a particular fascination with something, for example a keen interest in wheels. It is these repeated patterns of behaviour that are often referred to as schemas.

The term schemas is not widely understood, and can be mysterious to many working within the early years sector and to the majority of parents and carers. There is almost an air of smoke and mirrors about this theme. In fact, most childcare qualifications and parenting courses do not mention schemas, yet these repeated behaviours of children continually intrigue and perplex the adults who care for them and an understanding of schemas helps to interpret this behaviour. I hope that this book will clarify the term and make schemas more accessible to those working with or looking after young children.

I have observed that there can be a very academic slant in books on schemas and schematic behaviour, with theorists using language which I view to be inaccessible to many and rather technical (e.g. forms of thought, horizontal, dynamic schemas). For the purposes of this book, I take a more practical approach. I consider the action or movement that is repeated (connection, transporting, rotation, etc.) and I have chosen the terms that are already widely used to avoid any confusion. This should provide clarity and generally make schemas and schematic behaviour better understood. Many of the case studies I discuss in this book are children who I have studied over time. I have also included a Glossary which explains key words and phrases used in this book. These words are italicised in the text the first time they appear in the text.

What is a schema? The theory

Schematic behaviour has been researched, discussed and studied over the years by many theorists. Piaget is possibly one of the earliest and most widely recognised theorists who referred to patterns of behaviour or schemas in relation to thought and action. He believed that when young children repeat actions, they are able to transfer their ideas into similar situations or generalise them into early concepts about the world around them. Theorists sometimes call this idea forms of thought, which are ways of organising our thinking to help us to make sense of the world.

Other theorists suggest schemas are like pieces of ideas or concepts. This can be compared with children doing a jigsaw. They do not yet have all of the pieces so they try to make sense of the jigsaw according to the pieces they do have. Through repeating different actions, children are able to investigate whether what they think happens will happen again. If they were right, the jigsaw piece fits; if they were wrong, they may need to rethink and get another jigsaw piece.

Chris Athey defined schema as a pattern of repeatable behaviour.

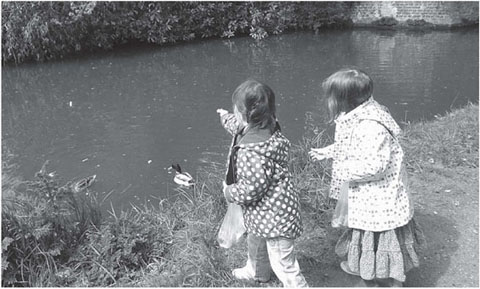

For example, when a child first learns to recognise a duck, they have made connections in their brain about the duck-ness of ducks. The repeated experience of seeing ducks confirms this. However, when introduced to a chicken for the first time, they may call it a duck, demonstrating their schema of thought and the similarities that they have noticed. The new information about chickens requires them to unlearn or rather fine-tune their earlier thinking and recognise the subtle differences between chickens and ducks.

Athey This rethinking and reframing as a result of assimilation is highlighted in the duck/chicken example above. The child needs to go through the process of accommodation and change their schematic thinking about ducks to incorporate the new information about chickens.

When children are engaging in schematic play, they are usually experimenting with what they can do unaided or independently. When we support and extend schemas, we aim to do so in Vygotskys Zone of Proximal Development , which is what children can do with additional support. Tuning into childrens language can provide an important insight into their schemas.

We can also talk to children about their learning and ask open-ended questions about what they are doing. This is engaging in sustained shared thinking with children and will support and extend childrens schematic play. Sustained shared thinking is a fairly new term that arose out of the Effective Provision in Pre-school Education (EPPE) research project and refers to when children work with an adult or more able peer to solve a problem or clarify and extend their thinking. We build on what children can do and extend their thinking by questioning, offering ideas or additional resources or through playing alongside and modelling a different approach.

It is important when questioning children that we do so in a developmentally appropriate way. Open-ended questions are the best sort to further engage children with it is better to use more concrete questions with younger children and move towards more abstract questions as children develop. For example, questions for babies and toddlers may include What is that?, What can you see? or more closed questions such as What isdoing? or Is it a? Questions for three- to four-year-olds might involve some analysis and progress to What is happening in this picture? or Find something that is and

Questions for a child aged four to five could include predictions, What will happen next?, or encourage thinking about the perspective of others, How do you think he feels? These questions are more challenging and require higher-order thinking skills as they are more abstract. Questions for children over five years old can incorporate problem solving, predictions, solutions and explanations. This requires children to use their own knowledge and thinking in order to answer the question. For example, What will happen if?, What should we do now? and, How did that happen?

Lets think about what this looks like for a child. Consider Liam, a fairly typical four-year-old boy who has an interest in wheels and things that rotate (see on rotation). We can scaffold his learning by offering him a simple problem to solve how do we attach the wheels to this car? Or extend his thinking by providing a selection of wheels to explore and investigate, for example, why do big wheels turn more slowly than small wheels? When Liam saw his grandads car stuck in the mud, he was very interested in watching the wheels spin round and round. We might ask Liam questions such as, Why do you think the wheel was spinning so fast but the car wasnt moving? and How can we help the car to move again?, which is engaging in sustained shared thinking with him. This is problem solving and cooperative thinking, when children and adults can together think deeply about a problem or puzzling scenario.

Next page