M ary F. Irish is a garden writer, speaker, and consultant in desert horticulturein Scottsdale, Arizona. She is coauthor, with her husband, Gary, of Agaves, Yuccasand Related Plants. She has also written numerous articles on desert plants and desertgardening for local, regional, and national publications and has been involved inthe electronic media in the Phoenix area, hosting the radio program Arizona Gardenerand playing an instrumental role in public television specials on desert gardening.She has taught classes and workshops and lectured on desert gardening both locallyand throughout the region. Ms. Irish was the Director of Public Horticulture forthe Desert Botanical Garden for 11 years, and during that time she managed the Gardensplant sales, plant introduction program, and public horticulture program.

1 Conditions of Desert Gardening

M y mother is still trying to figure out what I see in this place. As we drive aroundthe area, she cannot resist exulting, Oh, good, there is something green! or Oh,doesnt that green look good! whenever possible. She is not alone in this feeling.Countless new residents arrive in the low desert, thinking of thrusting their handsinto the dirt to create a new garden in their new home, and are chagrined to learnthat nothing seems to grow for them here. Failure piles up on failure; old favoritesburn up in the heat; trees and shrubs fail to thrive; annuals planted during benevolentMarch turn to dust by May; dirt more nearly resembles construction material; andthe sky never seems to cloud over and rain.

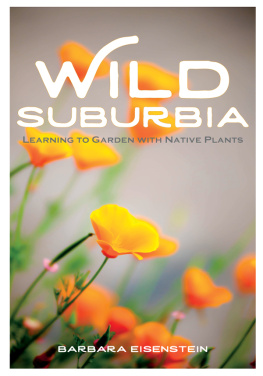

Amid such frustrating foreignness, new gardeners become increasingly disheartened.Many return to familiar habits and apply copious amounts of water to grow the gardensthey desire. But nostalgic lawns and garden magazine annuals do not fit the lookof a desert city and require shocking amounts of water. Other immigrants to the deserteschew intense watering in favor of sere, flat, gravel-covered yards with a solitarycactus, a lonely mesquite, and a few small boulders. This type of yard is certainlywater efficient, but it fails to reflect the rich possibilities of desert flora andis neither inviting nor comfortable.

Where are the flavor and form of the Moorish gardens that achieved exquisite successin similar climates hundreds of years ago? Where are the echoes of the great Spanish-Mexicancultural blend so evident in food and architecture but so weakly acknowledged inour gardens? In a climate so hospitable to outdoor living, why are gardens so severeand unfriendly? Is it that difficult to garden in the desert or to grow desert plants?

No, it is not. I think the key to more satisfying and rewarding gardening in a desertenvironment lies in selecting garden plants from the vast array of species nativeto the deserts and semiarid regions of the world rather than relying on plants frommilder, wetter, and more temperate climes. Desert and semiarid species have provedtheir ability to thrive in rigorous conditions. The gardener sacrifices nothing infunction, form, or beauty by using these plants; in fact, they are some of the mostluscious bloomers and have the most graceful forms and outstanding performance availableto gardeners anywhere. In addition, the diversity of desert plants is rapidly increasingas more plants from arid regions of the world are becoming available.

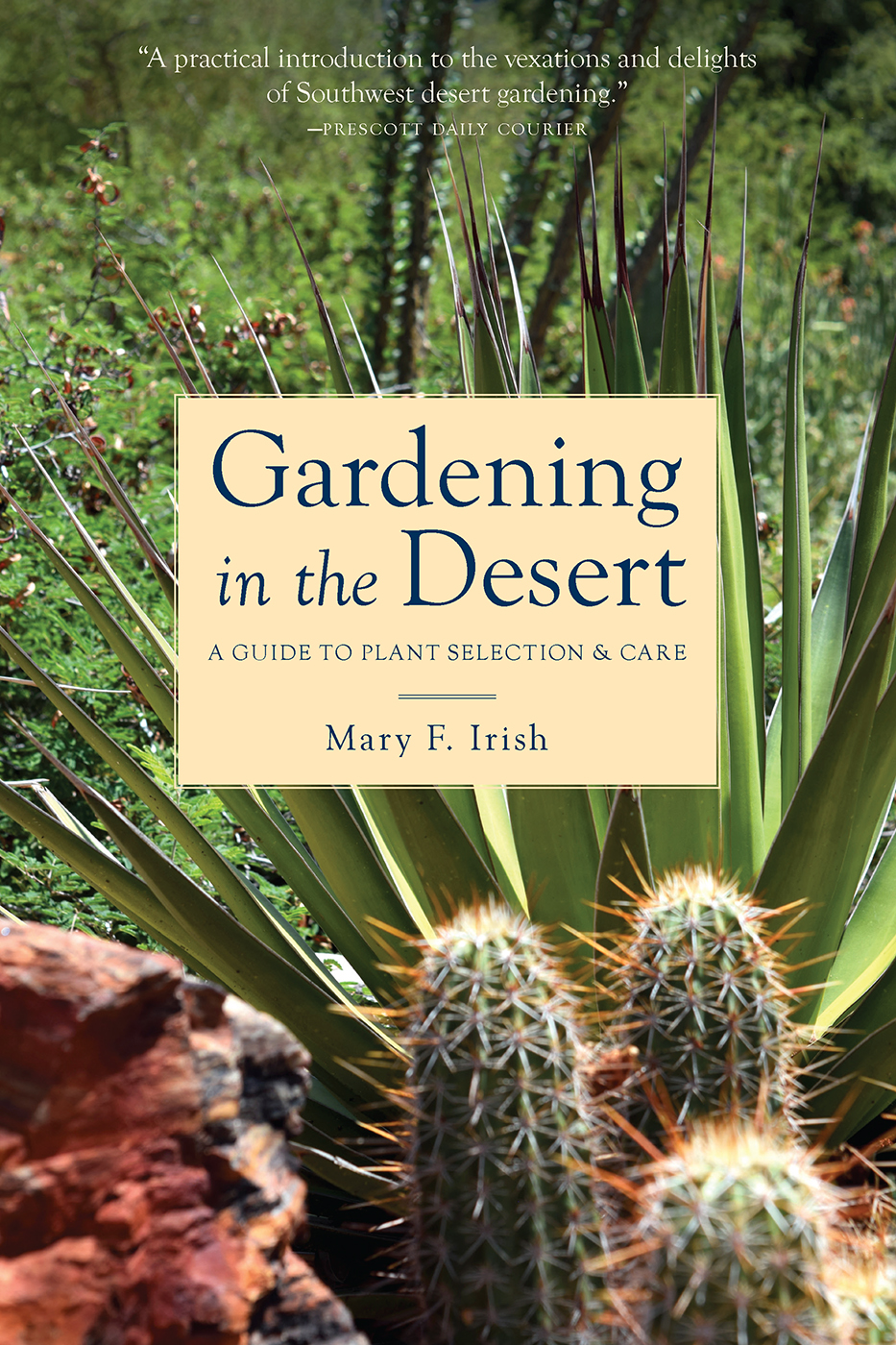

The increasing use of desert plants in the American Southwest is building a new traditionin desert gardening and a strong regional style. The use of diverse succulents givesthe arid garden a character, form, and substance quite different from that of thefrothy, leaf-dominated gardens of the eastern United States. The sharp, hard edgesof yuccas and agaves, with their intense symmetry, strong colors, and unexpectedor vivid color combinations, lend a wide range of styles and forms to the desertgarden.

In the low desert, gardening is a year-round activity, not so seasonally drivenas temperate zone gardening. Spring regales the area with a magnificent, althoughshort, bloom season, followed by the sensational late-spring bloom of cacti. Thena glorious fall bloom, especially among Chihuahuan shrubs, is followed by the longwinter bloom of various South African species. And regardless of how desperatelyhot and dry, summer is a feast of blooming plants.

Rocks should play a large role in the desert garden because they form the very architectureof our region. Distant, gargantuan mountains of rock outline the horizon; closer,they define a stream or the side of a hill. The intermittent placement of rocks ina garden provides dozens of tiny microclimates, which in turn make for greater speciesdiversity. I had a fine friend who grew the most perfect agaves. He maintained thathis success came from surrounding the base of the plants with rocks, which cooledthe roots below. Looking at his results, I believed him.

Gardening in the arid West is far different from gardening in all other regions ofthis country. Generally, the advice and information given in national magazines,seed catalogs, and books are ineffective in this region. Following those guidelinesoften leads to failure, frustration, and the conclusion that there can be no satisfactorygardening in the desert. Nothing could be further from the truth. Just as easternAmerican gardeners once struggled to release the firm bonds of English gardeningtraditions that did not work here, so, too, must western, and especially desert,gardeners free themselves from the expectations and routines determined by the conditionsof the eastern United States and discover the delights and joys of the gardens thatare possible in the arid West.

So I urge everyone who begins gardening here to start with an understanding of theconditions incumbent in the low desert regions of the American Southwest. They are:

a long growing season highlighted by a long, hot summer

a long growing season highlighted by a long, hot summer

soils that are low in organic content and highly alkaline

soils that are low in organic content and highly alkaline

meager annual rainfall with long periods of time between rains

meager annual rainfall with long periods of time between rains

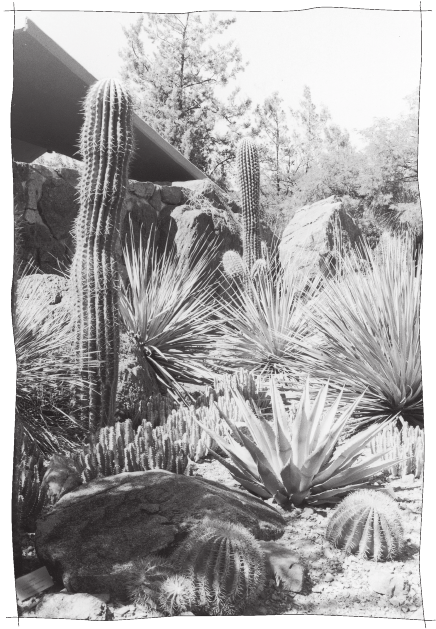

Desert garden scene GARY IRISH

These conditions dictate new ground rules for gardening:

The seasons are different here than elsewhere.

The seasons are different here than elsewhere.

Shade is highly desirable.

Shade is highly desirable.

Plants of desert origin already have the necessary adaptations to live successfullyin these conditions.

Plants of desert origin already have the necessary adaptations to live successfullyin these conditions.

Supplemental irrigation, at least to some extent, is a way of life.

Supplemental irrigation, at least to some extent, is a way of life.

Weather

I vividly remember the first time I stepped into the Arizona sunshine. I had beenconsidering a move here, and this was the trip to see if I liked it. It was MemorialDay, and when I walked off the plane and onto the tarmac at Sky Harbor Airport inPhoenix, the sheer brilliance of the light overwhelmed me. Colors were deep and intense,the air was sharp, edges were crisp and detailed, and it was quite hot. I did notknow until later that this experience encapsulated the nature and style of heatin the desert.

a long growing season highlighted by a long, hot summer

a long growing season highlighted by a long, hot summer soils that are low in organic content and highly alkaline

soils that are low in organic content and highly alkaline meager annual rainfall with long periods of time between rains

meager annual rainfall with long periods of time between rains