Build a Bluebird Trgail

Dale Evva Gelfand

Introduction

Two thoughts spring immediately to mind when hearing the words bluebird trail: What is a bluebird trail? And why is one necessary?

The Peterson bluebird box is one of the most popular designs used on bluebird trails.

A bluebird trail is simply a series of nesting boxes set some 300 feet (91.5 m) apart along a prescribed route from a couple to thousands of them. Many of the naturally occurring cavities in which bluebirds prefer to nest in standing dead trees and wooden fence posts have been destroyed. And while bluebirds have made a significant comeback in many areas, their continued survival depends, ironically, on their worst enemy: humans.

A Little History

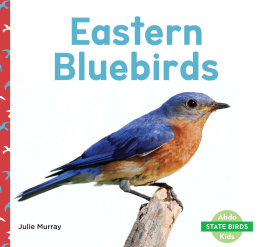

Bluebirds are members of the thrush (Turdidae) family. Across North America there are three species: the Eastern Bluebird, the Mountain Bluebird, and the Western Bluebird. During the 1700s and 1800s, bluebirds were at their peak of abundance. Small family farms were a combination of pastures, orchards, and woodlots ideal bluebird habitat. Bluebirds are cavity nesters, but unlike woodpeckers they cant drill their own holes, so they have to take advantage of existing cavities, either in trees living, dying, and standing dead ones (snags) or in fence posts.

Around the turn of the 20th century, all three species of bluebirds began suffering a drastic decline, with the Eastern Bluebird suffering most (enduring a 90 percent decrease, according to some experts, from about midcentury onward). This precipitous reduction was the direct result of the loss of suitable nesting sites caused by several factors: Many small family farms were relinquished, and the farmland either reverted to forest, was bought up by developers who routinely destroyed habitat, or was purchased by large agribusinesses whose operations required plowing expansive fields with no hedgerows whose bushes and trees were good both for nesting and for winter berries. Then woodstoves came into widespread use, and many of the snags that contained prime tree holes were harvested for firewood. Also, metal fence posts replaced wooden ones, eliminating even more nesting cavities.

Compounding the problem of insufficient nesting sites was the introduction in the late 1800s of two nonnative species: House Sparrows and European Starlings. These ubiquitous aliens directly compete for nesting sites with bluebirds, over which they unfortunately have a distinct edge. Because it is nonmigratory, the House Sparrow can claim nesting sites before bluebirds return in spring. And the aggressive behavior of both of these interlopers especially the House Sparrow puts bluebirds at risk at all stages of their lives: When a House Sparrow finds a bluebird nest, it will eliminate the bluebirds by breaking open eggs or pecking nestlings to death, and then drive off even kill any adults that attempt to defend their nest. Adding insult to literal injury, the invaders then build a new nest atop the bluebird nest, leaving the bluebird pair without a nesting site.

Two of the most aggressive competitors for bluebirds are the House Sparrow (left) and the European Starling (right).

Food shortages have also contributed to bluebird decline. During the summer bluebirds feed primarily on insects, but in winter they depend on wild berries and fruits for sustenance, and the same widespread development that has eliminated nesting sites has also eliminated food supplies. What little remains is often quickly stripped by flocks of European Starlings, which devour fruits and berries in early autumn and leave little for wintering bluebirds. And pesticides especially those used in orchards directly poison bluebirds as well as destroy the insects that the birds would normally eat. This is especially ironic because bluebirds consume great quantities of grasshoppers and cutworms, which are exceedingly damaging agricultural pests.

A Population on the Upswing

A number of years ago caring individuals and conservation groups throughout North America decided to improve the plight of these beautiful birds by setting up bluebird trails and providing artificial nesting cavities. The bluebird-trail concept started in 1934, when Thomas Musselman of Illinois, recognizing that bluebirds were losing the battle of the nesting sites to House Sparrows and starlings, began placing man-made bird boxes along rural roads until he had more than a thousand of them dotting Adams County. A Kentucky counterpart, William Duncan, also set up bluebird trails, using an excellent nesting box of his own design. Fortunately, bluebirds readily adapt to using man-made nesting boxes and in some cases even prefer the artificial cavities to the real thing. (One project that was started in 1959 by a junior birders group in Manitoba eventually extended 2,500 miles, or 4,000 km. Some 5,000 Eastern Bluebirds plus 10,000 Tree Swallows now fledge annually along this trail.)

A major bluebird upswing began with the formation in 1978 of the North American Bluebird Society (NABS). Its efforts in educating the public about the importance of sustaining bluebirds in their native habitat have resulted in a dramatic resurgence in the bluebird population, and bluebirds are now nesting where they havent been seen for decades. Thanks to the efforts of thousands of people, the bluebird comeback story can be counted as a conservation victory.

This booklet will assist you in doing your part in a nationwide network of dedicated conservationists by setting up your own bluebird trail. You can take pleasure in knowing you are helping sustain the beautiful creature that Henry Thoreau, in his impeccable wisdom, called His Most Serene Birdship.

A Summer in the Life of a Bluebird

The bluebird His Most Serene Birdship

Bluebirds are basically monogamous, at least through one breeding season, although some pairs breed together for more than one season. Males usually arrive several days to a week before the females to immediately search for suitable nesting sites. Once a male has established his territory which is often the same one in which he has previously bred he will defend it from other male bluebirds. A male bluebird can usually defend his territory without a fight, but sometimes he is driven off by his challenger.

When territorial ownership has been established, the males next imperative is to pair with a female. This is no problem, of course, for those pairs that arrive together. Otherwise, though, the male begins a round of courtship song to attract a female. When hes been successful, he leads his mate to several potential nesting sites that she can inspect and select from. She may, in fact, start to build a nest in more than one site, but eventually she chooses one and begins nest building in earnest. Now the pair strenuously defend their nesting territory. Theyre usually successful against other bluebirds, but may be less so defending against other cavity nesters.

Nest building, which typically takes four to six days, is done entirely by the female. Although the male bluebird may carry some of the nest-building material to the nesting site, and he does sing to the female while she gathers the bulk of the nesting material, he is primarily occupied with guarding her, ensuring that she doesnt go off and mate with another male.