Praise for Astroquizzical

A wonderful jaunt through the universe at every scale, and a great way to fill in every gap in knowledge you have about astronomy.

Zach Weinersmith, co-author of the New York Times bestseller, Soonish

Astroquizzical is a superb astronomy book, written with a distinctive tone which is both pragmatic and poetic at the same time. [Jillian Scudder] brings the perfect blend of fact and fascination to help us feel a greater sense of our place within the clockwork of the universe.

Jon Culshaw

Scudders mission is to provide the lay reader with a thorough grounding in the basics of astronomical knowledge. The writing is fluid and direct with the subject material brought vibrantly to life. For astro novices this book will bring a welcome depth to their appreciation of the night sky and the wonders it holds.

BBC Sky at Night magazine

Genuinely entertaining [with] an excellent balance of enthusiasm and facts. This is the kind of book that would be excellent to get either a teenage reader or an adult with limited exposure to astronomy interested in the field. Its a cosmic journey that I enjoyed.

Brian Clegg, popularscience.co.uk

ii The narrative form that Scudder employs is an imaginary cosmic journey that begins on our home planet and takes us in seven steps to the furthest galaxies. This simple format has been tried countless times before by big-name astronomers. Whats different here is an intense level of engagement between writer and reader. Vivid storytelling explains the physics without equations. Her aim is to get people to think issues through for themselves, and that works. The clarity of Scudders writing is impressive.

Simon Mitton, Times Higher Education

[This] excellent debut book is all about making complex concepts, if not exactly easy to understand, then at least a little easier to grasp. In her enthralling cosmic journey through space and time, astrophysicist Jillian Scudder discusses our home planets place in the universe. Beyond the flawless presentation of known facts and current thinking, Scudder explores further by positing counterfactuals and thought experiments. The real triumph of Scudders Astroquizzical is that it brings high-altitude, notionally abstract ideas to the general reader, presented in an entertaining and accessible way.

Engineering & Technology magazine

Astroquizzical approaches astronomy at a unique angle. It begins by stating that we are all distantly related to the stars; everything were made of can be traced back to when they explode. By making this comparison at the start of the book, you instantly become intrigued and involved and from then on, the author Jillian Scudder does a fine job of covering a variety of topics and interests in space science.

All About Space

CONTENTS

I have often introduced myself to students on the first day of class by saying I have three main interests in life: space, dinosaurs, and volcanoes. I am delighted to let you know that this book has all three, though of course its heavy on the space. But then, my life is also heavy on the space bit; my profession is teaching physics and astronomy. Whether my class is current events in astronomy, a general overview course of outer space for non-science students, or upper level astrophysics, I really enjoy the process of teaching people whats out there, how we know it, and all the things we still dont understand.

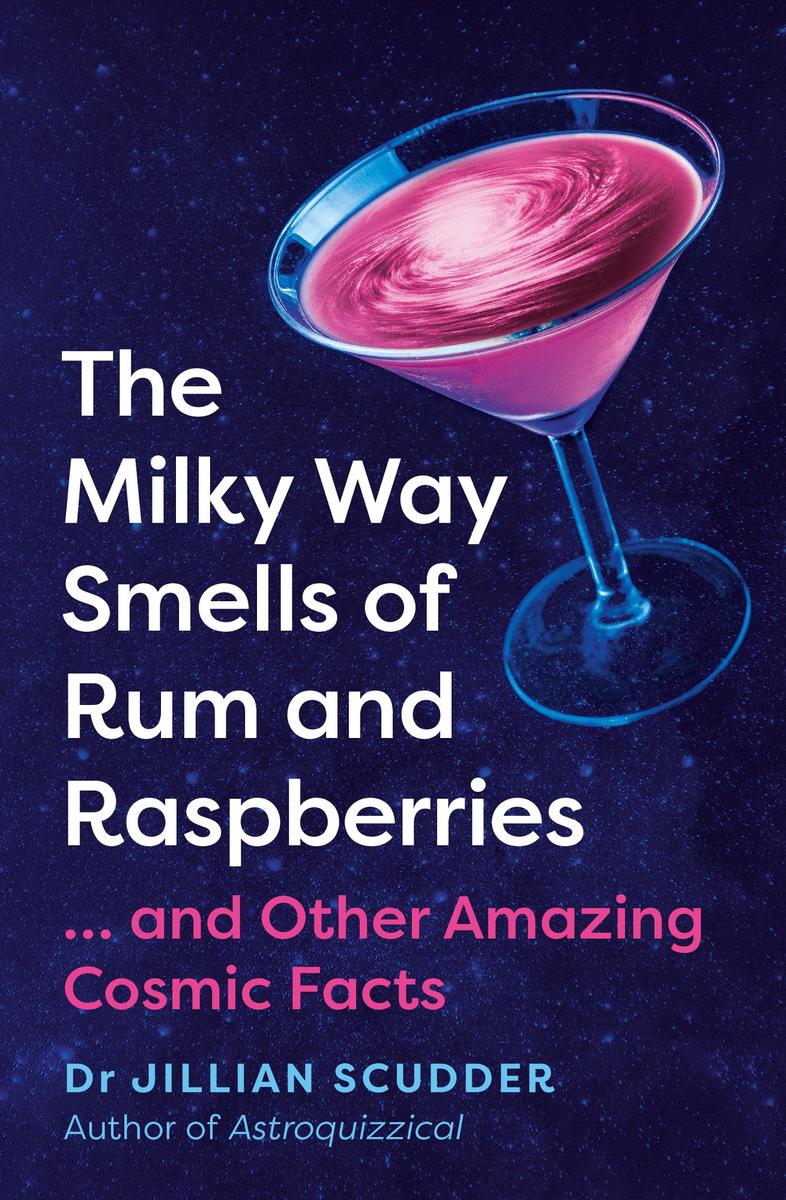

Astronomers have learned a lot about the Universe over the years, and some of the things weve learned sound very sensible, like that there are planets around many of the stars in our own galaxy, and that our Sun is pretty average in most regards, and that a lot of things have to go just right in order to have a planet that can grow trees. And then there is a whole pile of things weve learned that just sound silly.

What kind of Universe comes with explosive moon volcanoes, planets as black as tar, and galaxies shaped like jellyfish, anyway? (Ours does.)

This book is a light-hearted tour through some of the more nonsensical things we know about outer space. As absurd as these may sound, everything here is extensively sourced to peer-reviewed publications; full details can be found at the back xiv of the book, for those who want to know more, with a clear link back to let you know what part of the text they belong to.

I have done my best to summarize our current understandings of the topics discussed here. But, as with all science, these topics will be refined and re-examined over the years to come. Our interpretations of the observations may change. This doesnt mean that the observations we had before were wrong, but that we have more information now, and so the context for those measurements has altered. A great example of how dramatically interpretations can change in some circumstances: a planet we once thought might be diamond, we now think is probably lava. In other cases, our interpretations have remained stable, and barring some unexpected new piece of information are likely to stand the test of time.

In any case, as of the time of writing, this is the current state of affairs, and no matter what, this will stay true:

Space is weird, full of volcanoes, and it can kill you in many very creative ways.

Given the number of stars in our night sky, it might come as a surprise to learn that the Universe hasnt been this dark in a long, long time many billions of years.

Ten billion years ago, the galaxies in our Universe were forming a tremendous number of new stars a number which has never been matched, before or since. When new stars are formed, they are produced in all sizes, from tiny, dim, red, and practically immortal, to the enormous, bright blue stars which live for approximately no time at all. This difference in lifetime means that while you can see red stars for a long time, blue stars, due to their almost instantaneous deaths, flag a galaxy which is actively churning new stars into existence. And 10 billion years ago, there were more of these blue stars than at any other time in cosmic history.

To reflect this boom in star formation, this time period 10 billion years ago has been dubbed cosmic noon. Which means that the time following cosmic noon can be (and sometimes has been) called cosmic afternoon, and so we can easily extrapolate that we will be proceeding onwards to cosmic evening and eventually cosmic night, which would presumably be when galaxies more or less stop forming new stars.

If we take a census of all the galaxies we can find, and then order those galaxies by how far away they are from us (which is an easy way of putting them in age order, as well see below), the typical number of stars formed in a galaxy every year has done nothing but decline for the past 10 billion years. Its not a small drop, either its about a factor of ten. Meaning that every galaxy, typically, is forming ten times fewer stars than it was about 10 billion years ago. There are exceptions to every rule, of course, and there are still galaxies very near us forming ten times the number of stars that a normal galaxy nowadays would produce, but there are star-forming overachievers in every era. Ten billion years ago, there were still galaxies forming an above-average number of stars; its the average thats changed.