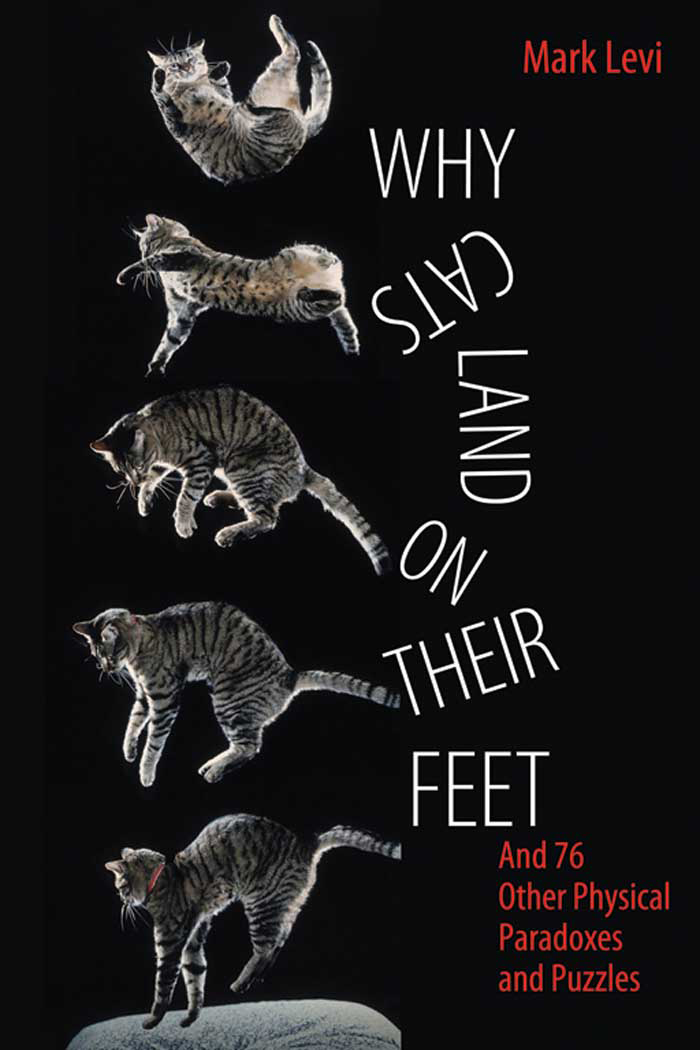

WHY CATS LAND ON THEIR FEET

Paradox: a seemingly contradictory statement

that may nonetheless be true.

Online dictionary

Puzzle: verb: to confound; noun: a toy

contrived to test ones ingenuity.

Online dictionary

Mark Levi

WHY

CATS

LAND

ON

THEIR

FEET

And 76 Other Physical

Paradoxes and Puzzles

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2012 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Levi, Mark, 1951

Why cats land on their feet, and 76 other physical paradoxes

and puzzles / Mark Levi.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-691-14854-0 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. ScienceMiscellanea. I. Title.

Q173.L545 2012

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Times

Printed on acid-free paper

Typeset by S R Nova Pvt Ltd, Bangalore, India

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

TO

Olga,

Kyra,

Eric,

Max,

Nika,

Vicki,

Jose,

and

Ryan

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to Paul Nahin for several very useful comments, in particular for pointing out the references to the Braess paradox, to Carole Schwager for numerous improvements of the exposition, and to Vickie Kearn, whose encouragement kept me going. I gratefully acknowledge support by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1009130.

WHY CATS LAND ON THEIR FEET

1

FUN WITH PHYSICAL PARADOXES, PUZZLES, AND PROBLEMS

1.1 Introduction

A good physical paradox is (1) a surprise, (2) a puzzle, and (3) a lesson, rolled into one fun package. A paradox often involves a very convincing argument leading to a wrong conclusion that seems right, or to a right conclusion that seems wrong or surprising. The challenge to find the mistakeor explain the surprisemay be hard to resist. A joke heard back in the Cold War years claimed that the West could impede Soviet military R&D efforts by scattering leaflets containing puzzlers and brainteasers over the secret Siberian weapons research facilities. Times have changed, and these same brainteasers now are used in hiring interviews. As a Soviet propagandist would have said: either way, they are a capitalist tool.

Resolving a paradox is not only fun; it also trains intuition, logic, and critical thinking. One becomes a better lie detector by resolving paradoxes. A good paradox also teaches caution and humility by showing us how easy it is to go wrong even in relatively simple matters of elementary physics. It is liberating to know that some very smart people offering even more room for mistakes there. In addition, some mistakes can be beneficial, at least temporarily.

My main reason in writing this book is to share the fun of imagining how things work. These paradoxes also teach the gist of some physics without the pain of mathematics.

The puzzles in this book deal with physicsa subject that walks on two legs, one being mathematics, and the other, physical intuition. Unfortunately, in school the subject is often presented with a severe limp.

A musical analogy. If music were taught the way physics often is taught, we would learn the notes but not the melodies they produce. For too many students of physics, the subject is reduced to a collection of formulas that must be matched to a problem at hand. Not surprisingly, many intelligent students are turned off.

Intuition should come first. Exercise of physical intuition is one practical benefit of this books puzzles. All too many physics courses give short shrift to intuition, emphasizing instead a search for the formula that fits the situation. Examples in this book go in the opposite direction: I tried for a minimum of formulas and a maximum of intuition. The discussion of the spinning top is an example, where I give a formula-free explanation of why the spinning top stays upright. It takes quite a few years of study in mathematics and physics to learn to write differential equations for the motion of a spinning top and to see how to deduce stability from these equations. And at the end of this long study few students end up with an intuitive understanding of why a spinning top stays up. The most powerful toolour physical intuitionends up unused.

1.2 Background

Much (but not all) of this book should be accessible to readers without formal background in physics. All physical concepts used are explained in the appendix. Mathematics in this book does not go beyond algebra, with a couple of exceptions where calculus is used. Even there, the reader who is willing to take a little math on trust should not be snagged by these references.

Attraction to anything surprising is a basic instinct in most living creatures, or, at least, most mammals. By driving us to explore, the instinct helps us survivewith some exceptions, such as Darwin Prize winners or the heroes of Jackass. The same instinct that drove Einstein to his great discoveries also drives a curious child to see whats inside a mechanical clock. It even drives puppies and cubs to explore. In some people this instinct is so strong it can survive the educational system.

1.3 Sources

This book grew out of a collection of puzzles I started long ago on my fathers advice, after I showed him one that it is most likely that others thought of them or of something equivalent before I was born. When I know the author or the origin of a puzzle, I make a reference.

Literature. Fortunately, much of the essence of basic physics can be understood, and enjoyed, without (m)any formulas, as some excellent popular books demonstrate. Among these are Walkers The Flying Circus of Physics, Epsteins Thinking Physics, Jargodzki and Potters Mad about Physics, and Perelmans classic Physics for Entertainment. Unfortunately, Makovetskys delightful book Smotri v koren (a loose translation: Seek the essence), which sold over a million copies in the former Soviet Union, does not seem to have been translated into English. Minnaerts The Nature of Light and Color in the Open Air, dedicated to optical phenomena in nature, will never age and will give pleasure to any curious individual lucky enough to open it.

This is not a statement on the relative difficulty of various sciences. I am simply referring to the fact that a physicist deals with much simpler objects (e.g., crystals) than a biologist (e.g., a cell).

I refer to pain" with tongue in cheekmathematics is of course indispensable and beautiful to me, at least, since its my job.

I am referring here to the sling problem on page 93 where the rock reaches infinite speed after one second.

For example, 2.1, 2.3, 2.4, 3.1, 3.2, 3.5, 3.6, 4.1, 4.2, 4.44.6, 5.35.8, 6.6, 6.7, 6.106.12, 8.2, 8.5, 8.6, 9.4, 11.1, 12.3, 13.2, 14.6, 14.8.

2

1

1