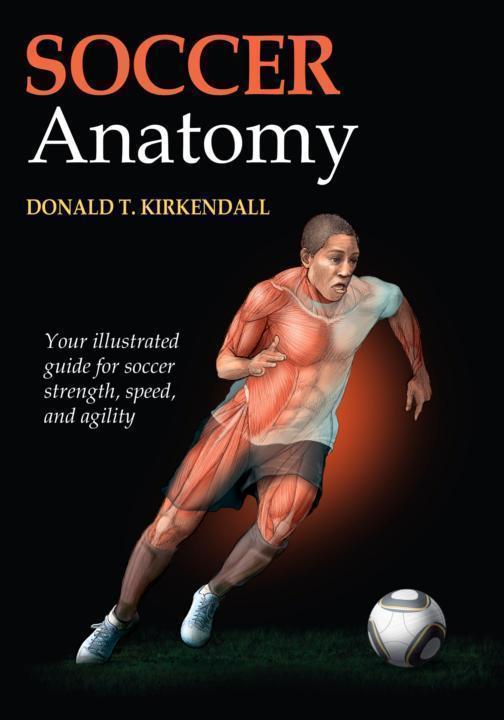

Donald T. Kirkendall, PhD

Preface v

CHAPTER

............ 1

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

............... 41

CHAPTER

........... 59

CHAPTER

............... 85

CHAPTER

..... 101

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

CHAPTER

.. 167

CHAPTER

........ 189

Then there is tactical brilliance. How about the 25-pass sequence to a goal by Argentina against Serbia in the 2006 FIFA World Cup, or the lightning-fast length-of-the-field counterattack for a goal by the United States against Brazil in the 2009 FIFA Confederations Cup final? Brazil's fourth goal against Italy in the 1970 World Cup is still considered a masterful display of teamwork, skill, and guile.

The objective of soccer is the same as in any other team sport: Score more than the opponent. This simple philosophy is enormously complicated. To be successful, a team must be able to present a physical, technical, tactical, and psychological display that is superior to the opponent's. When these elements work in concert, soccer is indeed a beautiful game. But when one aspect is not in sync with the rest, a team can be masterful and still lose. The British say, They played well and died in beauty."

Soccer, like baseball, has suffered under some historical inertia: "We've never done that before and won. Why change?" or "I never did that stuff when I played." That attitude is doomed to limit the development of teams and players as the physical and tactical demands of the game advance.

And oh how the game has advanced. For example, the first reports on running distance during a match noted English professionals of the mid 1970s (Everton FC) averaged about 8,500 meters (5.5 miles). Today, most distances average between 10,000 and 14,000 meters (6 and 8.5 miles). There are reports that females, with their smaller hearts, lower hemoglobin levels, and smaller muscle mass, can cover the 6 miles attributed to men. The distance and number of runs at high speed have also increased as the pace of the game has become more ballistic and powerful. To those of us who have followed the game over the years, the pros sure do seem to strike the ball a lot harder now.

But the benefits of soccer extend beyond the competitive game. Emerging evidence shows that regular participation in soccer by adults is as effective as traditional aerobic exercise such as jogging for general health and for treating certain chronic conditions. For example, people with hypertension can see reductions in blood pressure similar to that seen in joggers. Blood fats can be reduced. Increased insulin sensitivity means those with type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome should see benefits. Regular soccer helps people, youths or adults, who are attempting to lose weight. A host of benefits are possible, all from playing an enjoyable game. An interesting sidenote is that when those studies were concluded, a lot of joggers just quit, but soccer players looked at each other and said, "Great. Can we go play now?"

The game is not as embedded in American culture as it is in other countries. Around the world, families, neighbors, and friends play the game whenever they can. In the United States, this neverending exposure to soccer is not as evident, so upon joining a team, an American child does not possess the beginnings of a skill set obtained from free play with family and friends. The coach may well be the child's only exposure to the game, requiring almost all coaching to be focused on the ball, which may neglect some basic motor skills and supplementary aspects of fitness.

In particular, the soccer community-and not just in the United States-has viewed supplemental strength training with skepticism. In addition, soccer players tend to view any running that is longer than the length of a field as unnecessary, and they avoid training that does not involve the ball. But give them a ball and they will run all day. The problem is many coaches apply the principle of specificity of training too literally ("if you want to be a better soccer player, play soccer") and end up denying players training benefits that are proven to improve physical performance and prevent injury.

This book is about supplemental strength training for soccer. When developed properly, increased strength will allow players to run faster, resist challenges, be stronger in the tackle, jump higher, avoid fatigue, and prevent injury. Most soccer players have a negative attitude toward strength training because it is done in a weight room and does not involve the ball. These attitudes were taken into consideration when the exercises in this book were selected. Many can be done on the field during routine training, and some involve the ball.

When a player or coach does favor some strength training, the primary focus is usually the legs. But as any strength and conditioning specialist will tell you, a balance must be struck up and down the body because the body is a link of segments, chains if you will, and the most prepared player will have addressed each link of the chain, not just an isolated link or two. Furthermore, those same specialists will say that while one group of muscles may be important within a sport, to address that group alone and neglect the opposite group of muscles will result in an imbalance around that movement or joint. Imbalances are known to raise the risk of injury. It has been known for years that strong quadriceps and weak hamstrings increase the risk of knee injury, but it is also known that athletes with a history of hamstring injury not only have weak hamstrings but also have poor function in the gluteal muscles. Weak hamstrings are also implicated in low back issues.