Growing Herbs in Containers

excerpted fromThe Herbal Palate Cookbook

Maggie Oster and Sal Gilbertie

Introduction

Herb gardening in containers enjoys a long history. Early records show that the ancient Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians grew bay, myrtle, and other herbs in clay pots. The Moors of southern Spain were known for their lavish use of containers in courtyard gardens, while the classicism of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Italian gardens greatly relied on ornate stone and lead planters. With industrialization, Victorian and Edwardian gardeners had a plethora of elaborate containers from which to choose, ranging from cast-iron urns to those made of stone, lead, and terra-cotta. Planted with an ever-expanding array of tender plants, the conservatories and pristine lawns of these eras were brightened with exuberant pots of colorful flowers.

Today, container gardening is once more in the throes of a renaissance. For some, this is due to the limitations of space in high-rises and condominiums; for others, it may be due to the ease and accessibility of gardening in containers. Ultimately, people simply appreciate what has been known since antiquity: Pots overflowing with plants add beauty and dimension to the landscape. Best of all, container gardening is an ideal way to easily grow all the herbs you might want for cooking.

If you need to move your larger containers, place them on wheeled stands for easy transport.

Herb Gardening Preparations

In terms of herb gardening, container gardening is a method that truly goes hand-in-trowel. All of the many pages written on the growing of herbs can be reduced to three major factors that most herbs need to grow well: lots of sunlight, plenty of air circulation, and well-drained soil that is kept a little on the dry side. Growing herbs in containers and small raised beds readily meets these criteria. As a result, herbs grown in containers often do much better than those grown in the garden.

Preparing the Soil Mix

After sun, air, and soil moisture, the most important single element necessary for the success of container gardening is the soil mix. Plants grow best when their root systems are able to spread easily through the soil, getting the right balance of water, air, and nutrients. Too much or too little of any one will result in unhealthy or dead plants. The following is a recommended soil mix based on equal parts of four ingredients: topsoil, coarse perlite, peat moss, and coarse sand. Each of these items can be purchased at most garden supply stores.

The topsoil should be of good quality either from your own garden or, preferably, sterilized topsoil available in bags at garden centers. Perlite is volcanic pumice. It loosens the soil and keeps it from becoming compacted. Be sure to buy coarse perlite. Do not substitute vermiculite for the perlite, as herbs do not grow well in it. Peat moss adds humus to the soil. Alternatives to peat moss include expandable blocks of coconut fiber and homemade or purchased compost. The final ingredient is coarse sand or fine gravel, which ensures good drainage and soil aeration. Chicken or turkey grit can be substituted.

Fertilizers and pH

You may have read that herbs grow in poor soil, but the reality is that they respond well to some fertilization. A simple organic method of feeding is to use dehydrated cow manure and bonemeal. Both are widely available at garden centers. To one bushel of standard potting soil, add a generous cupful each of manure and bonemeal; mix it in thoroughly. Worth seeking out is either worm (see box below) or cricket compost if you can find it, use one of these composts instead of the cow manure. Alternatively, consider using one of the various complete organic or natural fertilizers that are commercially available. Use at the manufacturers recommended rate.

Because container plantings are watered frequently, the nutrients get washed away from the roots more quickly than in the garden. It is advisable to feed container-grown plants at least once a week when theyre actively growing. Either scratch granular organic fertilizer into the soil surface or water with a soluble organic fertilizer, if desired. With either method, follow the manufacturers recommendations. The easiest method is to choose what is called a complete fertilizer one that contains nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, as indicated by the three numbers on the bag. You can also mix your own from individual components.

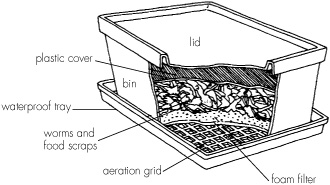

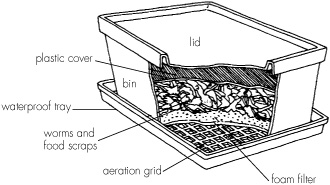

Worm Compost

You can recycle plant-matter and kitchen scraps by feeding them to worms to make worm compost. Mail-order sources carry special bins, starter worms, and a how-to book for producing this nutritious soil amendment and fertilizer in your basement or garage. So if you dont have space for a compost pile, you still can recycle and have a source for a healthy, organic soil amendment.

Fertilizers containing kelp or other seaweed and fish emulsion seem to particularly benefit plants; good mixes include enzymes, vitamins and minerals, liquid humus, marine algae, and chelating agents (which make minerals more readily available to plants).

The pH of a soil reflects the hydrogen ion concentration and affects nutrient uptake. The pH is based on a scale of 1 to 14, with 7 being neutral; numbers below 7 indicate an increasingly acidic soil and numbers above 7 indicate an increasingly alkaline soil. Most herbs grow in a pH range of 6 to 7, which is provided with the recommended soil mixture described above. If you want to be sure, you can check the soil pH before planting and then occasionally throughout the growing season. Inexpensive test kits or pH meters are available at garden centers. To make a soil more alkaline, thoroughly mix in some dolomitic lime; to make a soil more acidic, mix in some elemental sulfur powder.

Choosing Containers

The range of containers available, either commercially or from found objects, is staggering. Of these, the best materials for growing herbs are those that are porous. Porous containers allow the roots more access to air, and also allow soil to dry out more quickly (in general, herbs hate having wet feet). This narrows the range to containers made of terra-cotta and wood. Although plastic and fiber-glass pots are lightweight, their nonporous nature causes them to dry out more slowly than porous containers. If you want to experiment with nonporous containers, go ahead, but put most of your money and effort into wood and terra-cotta.

Advantages of Terra-cotta

Although terra-cotta pots are generally preferred for herbs, they have several disadvantages. Besides their cost and weight, these common, reddish clay pots are likely to crack and break in freezing weather. To prevent this, they must either be emptied and turned upside down before cold weather or stored in a garage or basement over the winter.

Another problem with clay is that, in the heat of summer, a terra-cotta pot can get very hot and dry out very quickly, especially if it is set on brick, stone, concrete, or asphalt. Because plant roots grow to the outside of the root ball, the heat and dry conditions can damage them. To alleviate this problem, raise the pot several inches above the surface or double-pot by inserting one container inside another and filling in between with long-fibered sphagnum moss.