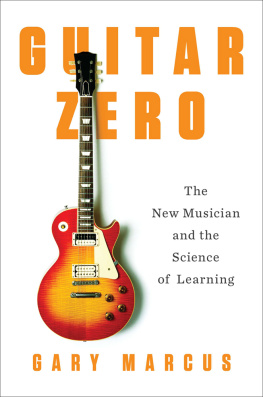

GUITAR

ZERO

ALSO BY GARY MARCUS

The Algebraic Mind

The Birth of the Mind

Kluge

The Norton Psychology Reader

(editor)

GUITAR

ZERO

The New Musician

and the Science

of Learning

GARY MARCUS

THE PENGUIN PRESS

NEW YORK

2012

THE PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)  Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL,

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL,

England  Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of

Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)  Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India  Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive,

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive,

Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2012 by The Penguin Press,

a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright Gary Marcus, 2012

All rights reserved

Illustration credits:

Pages 41 and 205: Athena Vouloumanos

Page 140: Gary Marcus

Pages 18 and 218: Meighan Cavanaugh based on sketches by the author.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Marcus, Gary F. (Gary Fred)

Guitar zero : the new musician and the science of learning / Gary Marcus.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

EISBN: 9781101552285

1. Musical ability. 2. Music Psychological aspects. I. Title.

ML3838.M44 2012

153.9 dc23

2011029941

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Designed by Meighan Cavanaugh

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the authors rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

For David and Elaine

Ive been obsessed with the guitar since I was twelve. In many ways my life has been one long conversation about the guitar, interrupted only by the countless hours of deep pleasure I have playing the darn things, as well as some less pleasant time spent doing what needs to be done so that I can get back to playing and chatting about them.

Perry Beekman, jazz guitarist

First you learn your instrument, then you learn the music, and then you forget all that s**t and just play.

Charlie Parker

CONTENTS

TUNING UP

What Does It Take to Become Musical?

A re musicians born or made?

All my life I wanted to become musical, but I always assumed that I never had a chance. My ears are dodgy, my fingers too clumsy. I have no natural sense of rhythm and a lousy sense of pitch. I have always loved music but could never sing, let alone play an instrument; in school I came to believe that I was destined to be a spectator, rather than a participant, no matter how hard I tried.

As I grew older, I figured my chances only diminished. Our lives, once we finish school, tend to focus on execution rather than enrichment. Whether we are breadwinners or caretakers, our success is measured by outcomes. The work it takes to achieve those outcomes, we are meant to understand, is something that should happen quickly and behind closed doors. If the conventional wisdom is right, by the time we are adults its too late to learn anything new. Children may be able to learn anything, but if you wanted to learn French, you should have started when you were six.

Until recently, science supported this theory. Virtually everybody in developmental psychology was a firm believer in critical periods of learning. The idea is that there are particular time windows in which complex skills can be learned; if you dont learn them by the time the window shuts, you never will. Case closed.

But the evidence for critical periods is surprisingly weak. Consider, for example, the often-cited case of Genie, an unfortunate girl who was locked in a silent room for many years. When Genie escaped at the age of thirteen, she was exposed to language for the first time, and she was never able to become fluent. Her vocabulary was good enough to get her started, but her grammar was a mess, filled with utterances like Spot chew glove and Applesauce buy store. Does this mean that Genies critical period for language had passed? Most people interpret her case that way, but another explanation, less often considered, is that Genies inability to learn language may have come in part from the emotional trauma (and perhaps malnutrition) she had suffered early on. Her case is consistent with the critical period hypothesis, but it certainly doesnt prove it.

The more people have actually studied critical periods, the shakier the data have become. Although adults rarely achieve the same level of fluency that children do, the scientific research suggests that differences typically pertain more to accent than to grammar. Meanwhile, contrary to popular belief, theres no magical window that slams shut the moment puberty begins. In fact, in recent years scientists have identified a number of people who have managed to learn second languages with near-native fluency, even though they only started as adults.

If critical periods arent quite so firm as people once believed, a world of possibility emerges for the many adults who harbor secret dreams whether to learn a language, to become a pastry chef, or to pilot a small plane. And quests like these, no matter how quixotic they may seem, and whether they succeed in the end or not, could bring unanticipated benefits, not just for their ultimate goals but for the journey itself. Exercising our brains helps maintain them, by preserving plasticity (the capacity of the nervous system to learn new things), warding off degeneration, and literally keeping the blood flowing. Beyond the potential benefits for our brains, there are benefits for our emotional well-being, too. There may be no better way to achieve lasting happiness as opposed to mere fleeting pleasure than pursuing a goal that helps us broaden our horizons.

Next page