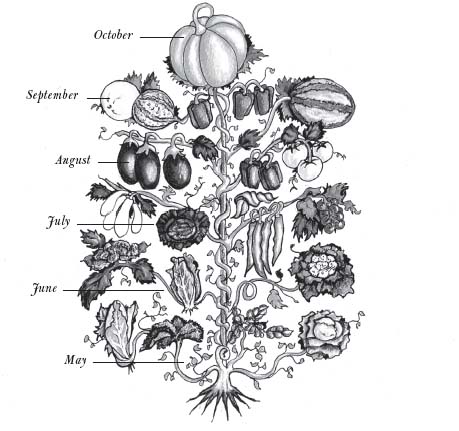

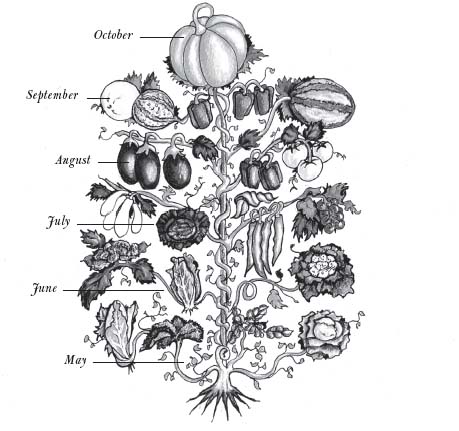

Picture a single imaginary plant, bearing throughout one season all the different vegetables we harvestwell call it a vegetannual.

This story about good food begins in a quick-stop convenience market. It was our familys last day in Arizona, where Id lived half my life and raised two kids for the whole of theirs. Now we were moving away forever, taking our nostalgic inventory of the things we would never see again: the bush where the roadrunner built a nest and fed lizards to her weird-looking babies; the tree Camille crashed into learning to ride a bike; the exact spot where Lily touched a dead snake. Our driveway was just the first tributary on a memory river sweeping us out.

One persons picture postcard is someone elses normal. This was the landscape whose every face we knew: giant saguaro cacti, coyotes, mountains, the wicked sun reflecting off bare gravel. We were leaving it now in one of its uglier moments, which made good-bye easier, but also seemed like a cheap shotlike ending a romance right when your partner has really bad bed hair. The desert that day looked like a nasty case of prickly heat caught in a long, naked wince.

This was the end of May. Our rainfall since Thanksgiving had measured less than one inch. The cacti, denizens of deprivation, looked ready to pull up roots and hitch a ride out if they could. The prickly pears waved good-bye with puckered, grayish pads. The tall, dehydrated saguaros stood around all teetery and sucked-in like very prickly supermodels. Even in the best of times desert creatures live on the edge of survival, getting by mostly on vapor and their own life savings. Now, as the southerntier of U.S. states came into a third consecutive year of drought, people elsewhere debated how seriously they should take global warming. We were staring it in the face.

Away went our little family, like rats leaping off the burning ship. It hurt to think about everything at once: our friends, our desert, old home, new home. We felt giddy and tragic as we pulled up at a little gas-and-go market on the outside edge of Tucson. Before we set off to seek our fortunes we had to gas up, of course, and buy snacks for the road. We did have a cooler in the back seat packed with respectable lunch fare. But we had more than two thousand miles to go. Before we crossed a few state lines wed need to give our car a salt treatment and indulge in some things that go crunch.

This was the trip of our lives. We were ending our existence outside the city limits of Tucson, Arizona, to begin a rural one in southern Appalachia. Wed sold our house and stuffed the car with the most crucial things: birth certificates, books-on-tape, and a dog on drugs. (Just for the trip, I swear.) All other stuff would come in the moving van. For better or worse, we would soon be living on a farm.

For twenty years Steven had owned a piece of land in the southern Appalachians with a farmhouse, barn, orchards and fields, and a tax zoning known as farm use. He was living there when I met him, teaching college and fixing up his old house one salvaged window at a time. Id come as a visiting writer, recently divorced, with something of a fixer-upper life. We proceeded to wreck our agendas in the predictable fashion by falling in love. My young daughter and I were attached to our community in Tucson; Steven was just as attached to his own green pastures and the birdsong chorus of deciduous eastern woodlands. My father-in-law to be, upon hearing the exciting news about us, asked Steven, Couldnt you find one closer?

Apparently not. We held on to the farm by renting the farmhouse to another family, and maintained marital happiness by migrating like birds: for the school year we lived in Tucson, but every summer headed back to our rich foraging grounds, the farm. For three months a year we lived in a tiny, extremely crooked log cabin in the woods behind the farmhouse, listening to wood thrushes, growing our own food. The girls (for another child came along shortly) loved playing in the creek, catching turtles, experiencing real mud. I liked working the land, and increasingly came to think of this place as my home too. When all of us were ready, we decided, wed go there for keeps.

We had many conventional reasons for relocation, including extended family. My Kingsolver ancestors came from that county in Virginia; Id grown up only a few hours away, over the Kentucky line. Returning now would allow my kids more than just a hit-and-run, holiday acquaintance with grandparents and cousins. In my adult life Id hardly shared a phone book with anyone else using my last name. Now I could spend Memorial Day decorating my ancestors graves with peonies from my backyard. Tucson had opened my eyes to the world and given me a writing career, legions of friends, and a taste for the sensory extravagance of red hot chiles and five-alarm sunsets. But after twenty-five years in the desert, Id been called home.

There is another reason the move felt right to us, and its the purview of this book. We wanted to live in a place that could feed us: where rain falls, crops grow, and drinking water bubbles right up out of the ground. This might seem an abstract reason for leaving beloved friends and one of the most idyllic destination cities in the United States. But it was real to us. As it closes in on the million-souls mark, Tucsons charms have made it one of this countrys fastest-growing cities. It keeps its people serviced across the wide, wide spectrum of daily human wants, with its banks, shops, symphonies, colleges, art galleries, city parks, and more golf courses than you can shake a stick at. By all accounts its a bountiful source of everything on the human-need checklist, save for just the one thingthe stuff we put in our mouths every few hours to keep us alive. Like many other modern U.S. cities, it might as well be a space station where human sustenance is concerned. Virtually every unit of food consumed there moves into town in a refrigerated module from somewhere far away. Every ounce of the citys drinking, washing, and goldfish-bowl-filling water is pumped from a nonrenewable sourcea fossil aquifer that is dropping so fast, sometimes the ground crumbles. In a more recent development, some city water now arrives via a three-hundred-mile-long open canal across the desert from the Colorado River, whichowing to our thirstsis a river that no longer reaches the ocean, but peters out in a sand flat near the Mexican border.

If it crosses your mind that water running through hundreds of miles of open ditch in a desert will evaporate and end up full of concentrated salts and muck, then let me just tell you, that kind of negative thinking will never get you elected to public office in the state of Arizona. When this giant new tap turned on, developers drew up plans to roll pink stucco subdivisions across the desert in all directions. The rest of us were supposed to rejoice as the new flow rushed into our pipes, even as the city warned us this water was kind of special. They said it was okay to drink, but dont put it in an aquarium because it would kill the fish.