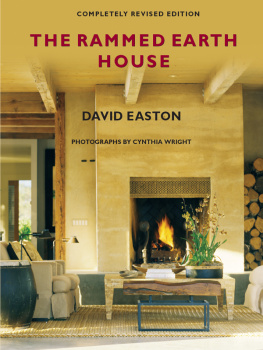

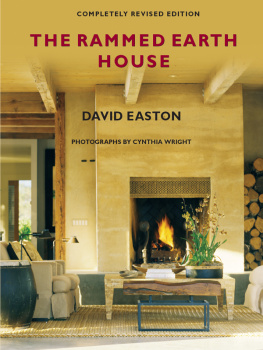

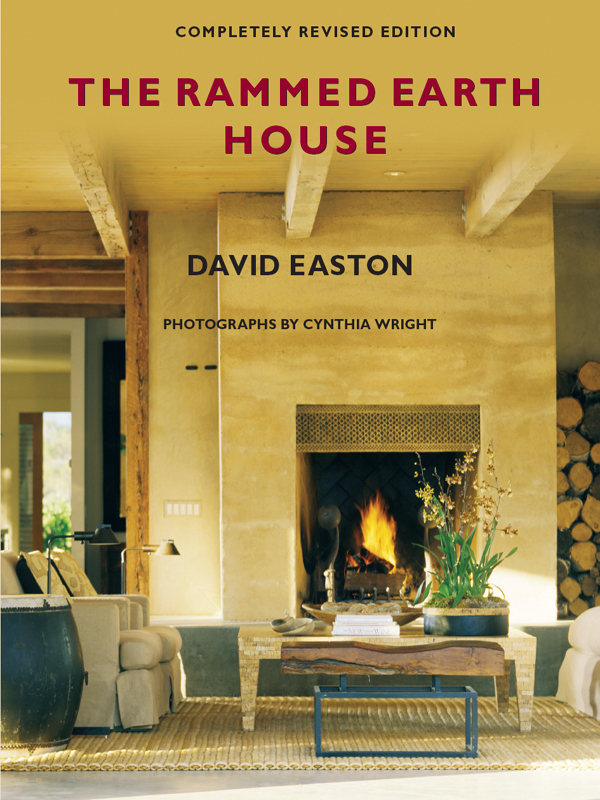

THE RAMMED EARTH HOUSE

THE RAMMED EARTHHOUSE

Revised Edition

David Easton

Photographs by Cynthia Wright

Chelsea Green Publishing CompanyWhite River Junction, Vermont

Copyright 2007 David Easton. Unless otherwise credited, photographs Cynthia Wright. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be transmitted or reproduced in any form by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

Editor: John Barstow

Copyeditor: Cannon Labrie

Proofreader: Collette Leonard

Designer: Robert A. Yerks, Sterling Hill Productions

Design Assistant: Abrah Griggs, Sterling Hill Productions

Printed in the United States

First printing, May 2007

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Chelsea Green sees publishing as a tool for cultural change and ecological stewardship. We strive to align our book manufacturing practices with our editorial mission and to reduce the impact of our business enterprise on the environment. We print our books and catalogs on chlorine-free recycled paper, using soy-based inks, whenever possible. Chelsea Green is a member of the Green Press Initiative (www.greenpressinitiative.org,) a nonprofit coalition of publishers, manufacturers, and authors working to protect the worlds endangered forests and conserve natural resources.

Rammed Earth House was printed on New Life Opaque, a 30 percent post-consumer-waste recycled, old-growth- forest-free paper supplied by R.R. DonnelleyWillard, OH.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Easton, David, 1948

The Rammed earth house / David Easton ; photographs by Cynthia Wright. -- Rev. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eBook ISBN: 978-1-603581-59-2

1. Earth houses--Design and construction. 2. Pis. I. Title.

TH4818.A3E27 2007

693.2--dc22

2007003504

Chelsea Green Publishing Company Post Office Box 428 White River Junction, VT 05001 (800) 639-4099 www.chelseagreen.com

This contribution to the expanding body of knowledge of rammed earth has been enhanced by the artful hand of Jeff Reed and the view of earth through the lens of Cynthia Wright. To my friend and to my wife I am forever grateful.

Contents

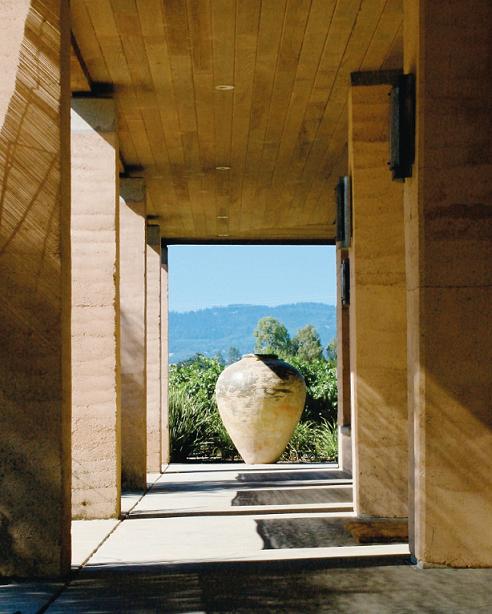

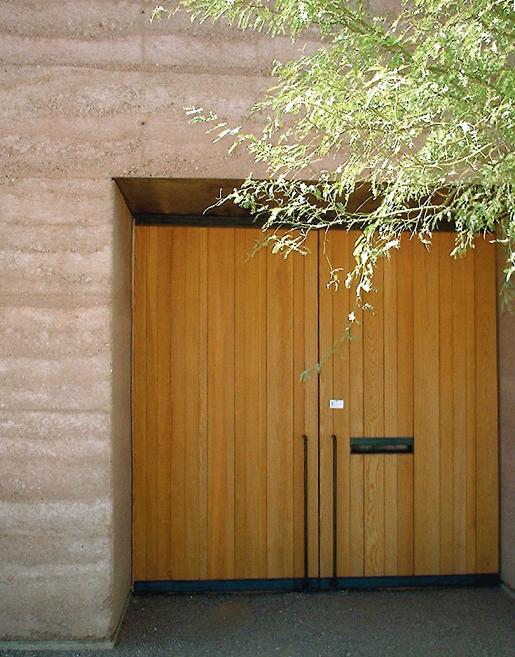

Theres a certain magic one feels inside a house with thick earthen walls. Its hard to describe, but easy to notice. Just take a step inside one on a hot summer day and youll feel it immediately. Its cool, of courseeveryone knows adobe houses are warm in the winter and cool in the summerbut theres something else to the feeling thats a little harder to name. Its quiet; the house feels solid and sturdy, calming, comfortable, timeless. Inside, you are reacting to the coolness emanating from the walls themselves and the buffering of ambient sounds, but inherently the je ne sais quoi of an earthen French country farmhouse or a California mission is actually a part of our evolutionary memory: We are hardwired to be at home in earth.

The idea of what makes a house has changed as much over the millennia as what a house is made of. Long ago, shelter was, well, shelter. Then, gradually it evolved. As human tolerance for discomfort decreased, the desire for features like warmth, spaciousness, and eventually, style, increased. At first houses were made of whatever was available, usually raw earth and raw wood. Over time, a range of manufacturing processes were developed for modifying earth and wood into other shapes and forms. Fired bricks and clay roof tiles are made of earth. Cement, concrete, stucco, and sheetrock also have their roots in earth, since each is the result of mining and processing minerals. The timber industry has progressed from hand-hewn logs to sawn boards to framing lumber and now even to wood chips glued back into the shape of boards.

Most Americans have grown up with the idea that a house is a lightweight box with walls assembled from thin sticks covered on both sides with even thinner skins. (Some societies think of this as a tent.) The floors and roofs are also built of sticks with equally thin skin coverings. As energy costs increased, builders started using an expanded petrochemical substancefiberglass insulationto fill the empty spaces inside the walls, floors, and roofs. Then as energy costs continued to increase, the industry invented another petrochemical productTyvek, a sort of plastic bagto wrap around the entire house. The fiberglass insulation and wrapping are intended to reduce heat loss through the building elements. The image this conjures up for me is of wearing a fiberglass sweater encased in clear plastic wrap. This is a far cry from the magic of thick earth walls.

Not that long ago, houses were built to last for generations. People actually lived in a house long enough to think of it as home. People died in the same house in which they were born. It made sense to invest in longevity if ones children, grandchildren, and even their grandchildren would be living there. Times have changed of course, and in our fast-paced world few of us expect to die in the same city we were born in, let alone the same house. This doesnt mean, however, that we cant still appreciate the special qualities of a house built solidly enough to last for several hundred years.

Think of the savings in natural resources that would result if todays houses were built to last longer. We could reduce the need to demolish houses and bury them in landfills, and we wouldnt need to harvest and process virgin resources to rebuild them. A structure constructed of solid materials, whether earth, brick, concrete, or stone, requires a larger investment on the front end, but as the generations roll by and stick houses roll into the landfill the environmental benefits are expressed in healthy dividends. Over time a building settles into its site, creating a sense of attachment and belonging. Trees and shrubs grow to maturity around the building. Successive occupants make their individual contributions to the personality of the house.

This book is about building a house for longevity. Its about a shift in attitude that takes into consideration the effects our choices have on future generations. Decisions about what materials to use, whom to buy them from, and how far to transport them have an impact on the long-term health of the planet. Even though you may one day move out of the house you have built and away from the garden you nurtured, the attitude of building for the future can benefit everyone.

The techniques described in this book are compiled from thirty years of experimenting with ways to build houses that grow out of their landscape. Ive been on a personal mission to reconnect people with natural materials and resources available on site. The material I am drawn to is raw earth. Most of this book deals with techniques for how to build using earth, primarily rammed earth.

In the mid-1970s, I was making plans to build my own house. Since I had far more time and energy than I had money, using a free resource, earth, for building the walls seemed logical. I had come across articles about the use of soil and cement by the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers during my studies in the civil engineering department at Stanford in the late 1960s and I had even conducted some small testing of soil cement. In terms of load-bearing walls, however, I had no knowledge of any earth-wall system other than the sun-dried adobe bricks used to build the California missions. When I was young, my family traveled to all the missions, teaching us about California history. I remember how those big, shady, cool buildings felt inside. Perhaps it was those early impressions that inspired my lifes work.

Next page