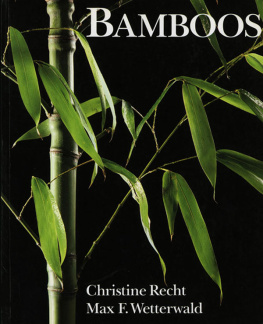

BAMBOOS

BAMBOOS

Christine Recht and Max F. Wetterwald

edited by David Crampton

translated from the German by Martin Walters

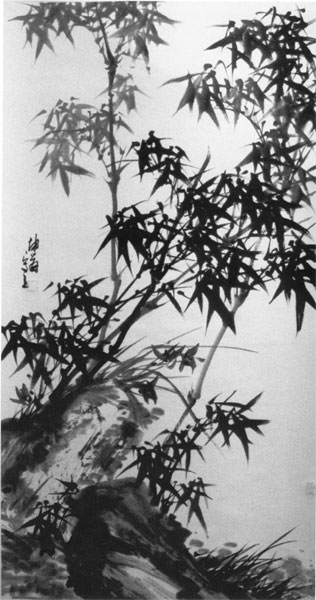

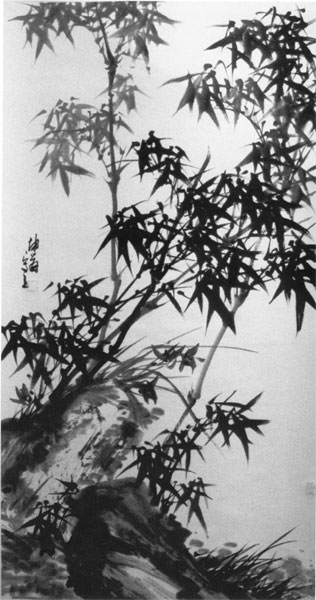

Frontispiece:

Grass, bamboos, orchids and rocks,

Chinese fabric-drawing, Lu Kunfeng (1980)

Published as eBook in the United Kingdom in 2015

First published in 1992

Reprinted 1993/1994/1995/1996/1998/1999/2000

First published in paperback 2001, reprinted 2002

Translation B.T. Batsford Ltd 1992

German edition 1988 by

Eugen Ulmer GmbH & Co.,

Stuttgart, Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

Batsford

1 Gower Street

London WC1E 6HD

An imprint of Pavilion Books Company Ltd

eISBN 9781849942133

Foreword

Bamboos are fascinating plants fascinating in their beauty and elegance, in their varied shapes and in their unusual qualities. Bamboos are simultaneously hard and soft, their stems are straight and yet flexible, their leaves graceful and green all year. Small wonder that these plants, which are already in vogue in America, are getting more and more popular in Europe.

Most bamboos come from Asia. There they are important in everyday life. All kinds of use is made of them their shoots are eaten and bamboo groves are a feature of the natural landscape. Bamboos also influence the art and culture of many Asian people. In China they are seen as the embodiment of the Chinese way of life: yielding, yet always victorious.

In Europe, bamboo is mainly a decorative plant, an exotic that survives our climate and fits into the landscape. Many species are frost-tolerant and decorate our gardens in winter with their soft foliage. Bamboos can be used in so many different ways, like scarcely any other group of plants. They fit into both small and large gardens, where they can grow in groves, as a hedge, and also as individual plants. They can therefore be used both in a supporting role and as a main performer in the garden. They are effective on terraces, balconies, in conservatories, and even on roofs.

More and more nurseries offer container-grown bamboos. Some outlets have specialized in bamboo propagation and now have a hundred or more different species available. Bamboos are very beautiful but until recently we have not known how to deal with them effectively. Fascination with bamboos has led many gardeners to buy them, but ignorance of their requirements has often brought frustration and despair.

This book will therefore help all bamboo enthusiasts. It will explain how to treat these magical plants and point out which sites suit particular bamboo species well and where they look best. It will increase understanding of these fine plants and enable gardeners to succeed with them by understanding their particular requirements.

When writing about bamboos one feels rather like the bamboo painters of ancient China who said: If you want to paint a bamboo you have to become one of their kind. It is particularly difficult to write a book about bamboos in Germany and to collect together the basic information, because there are so few experts.

I should like to thank all those who have helped me with their knowledge, experience and passion for bamboos: Werner Simon, Marktheidenfeld, who as co-author collated and described all the species that can be cultivated in Germany; Albrecht Wei from Seeheim-Jungenheim, who put his extensive knowledge and long experience of bamboos at my disposal and who also infected me with his enthusiasm, as did Ullrich Willumeit, Darmstadt. Thanks also to Dr. Warda of the New Botanic Garden, Hamburg where Max Wetter-wald was able to photograph bamboos, and to Wolfgang Eberts, Baden-Baden, who always knew the answers to particular problems as well as the most beautiful bamboo gardens to photograph.

Christine Recht

Bamboos in Asiatic Culture

Bamboo is my brother, so goes a Vietnamese proverb. This demonstrates precisely the relationship of almost all Asiatic people, even today, with this plant. From China to India, from the moist, primeval forests to the cool mountain foothills, bamboo is such a natural partner to humans in all walks of life that to live without it is scarcely imaginable. It is quite possible not to eat meat, but not to be without bamboo, so said Su Dongpo (10361101), the greatest poet and artist of the Song Dynasty. It goes deeper than this, however. In ancient China people identified with bamboo, the symbol of the Chinese way of life. Bamboo stands for elasticity, endurance and tenacity. Bamboo bends in the breeze, but does not break. The leaves are moved by the wind, but do not fall. Bamboo therefore survives and conquers.

In Japan this characteristic is still known as a bamboo mentality: to make compromise, to yield, and eventually to go forward unbroken from all contests. In Asia bamboo embodies the ideas of Taoism, laid down mainly by Laotse. These ideas describe the art of survival as yielding and then coming back again.

Religion and symbolism

In all Asiatic countries religion is closely connected with nature. The gods, of which there were and still are countless numbers, lived in the rocks, in the water, woods, and hedgerows. Individual stones, rivers and trees were also held to be holy, although not in the European sense of the word. Water, mountains, plants and animals were seen not as inferior to humans but as part of a whole, to which people also belong. The belief that humanity cannot exist without nature, and that we must live by its laws in order to survive is still held in modern Asia. With this appreciation of the unity of humanity and nature one can understand why in Asia bamboo is considered as a friend, or a travelling companion.

It is not only bamboo that plays a leading role in Asiatic religion, philosophy and art; pine, willow, plum, lotus flower and chrysanthemum are also important. But of all these symbolic and revered plants, it is the bamboo alone that is put to practical use, be it as building material, food, or for making thousands of objects in daily use. Bamboo is of special significance in Asiatic, and particularly Chinese, symbolic language. It droops its leaves because its inner self (that is its heart) is empty. An empty heart in China means modesty, so bamboo is a symbol for this virtue. Bamboo is evergreen and does not change its appearance with the seasons. It is therefore held as a symbol of age. The Chinese character for bamboo is similar to that for laughter, because the Chinese believe that the bamboo plants bends when it hears laughter. In Chinese, the words for bamboo, prayer and wish all sound the same. The reason is as follows: sticks of bamboo explode if placed in a fire, with a loud crack. The bamboo firework was supposed to drive away demons and ensure that the gods heard prayers and wishes for peace and tranquillity.

In Asian art bamboo is often illustrated together with orchids or plum blossom. The flowers embody woman or yin, the female element, bamboo the man or yang, the male element.

Because bamboo plays such an important role in peoples lives in Asia, in philosophy as well as in everyday practical life, it has become a part of legend, belief and superstition. There are countless fairy-tales and legends in Asia concerning bamboos. Here is an example: When a Japanese farmer was cutting bamboo he found a tiny girl inside a bamboo culm. He took her home and brought her up as his own child. She grew up to be one of the most beautiful and charming girls in the whole country. The emperor of Japan heard about her and wanted to marry her. However, the girl wrote him a letter saying that it was too great an honour for her and she decided to return to the bamboo. The emperor sent all his soldiers to find her, but without success, and in sadness at losing the bamboo girl he burned her letter on top of the mountain, Fujiyama, where the fire still burns to this day.

Next page