ALSO BY ARNOLD WEINSTEIN

Northern Arts

Recovering Your Story

A Scream Goes Through the House

Vision and Response in Modern Fiction

Fictions of the Self: 15501800

The Fiction of Relationship

Nobodys Home: Speech, Self, and Place in American Fiction

from Hawthorne to DeLillo

Copyright 2011 by Arnold Weinstein

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Permissions acknowledgments can be found on .

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Weinstein, Arnold L.

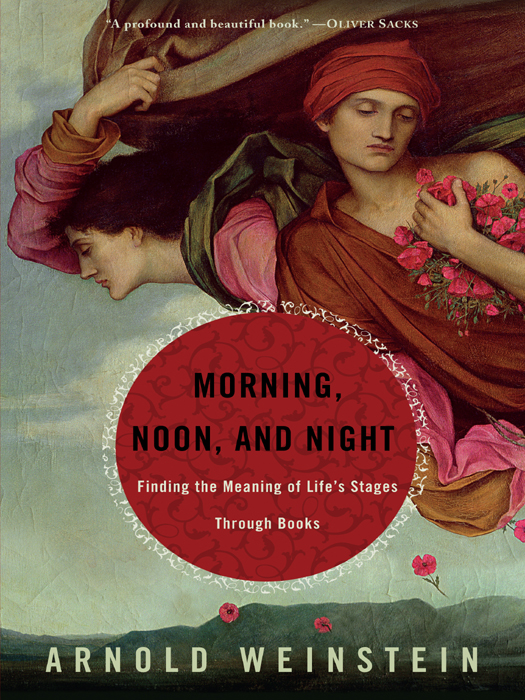

Morning, noon, and night: finding the meaning of lifes stages through books/by Arnold Weinstein.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-679-60447-1

1. Life cycle, Human, in literature. 2. Human beings in literature. 3. Maturation (Psychology) in literature. 4. Aging in literature. 5. Literature, ModernHistory and criticism. I. Title.

PN56.L52W45 2011

809.93354dc22 2010017523

www.atrandom.com

Jacket design by Susan Zucker Koski

Jacket painting: Evelyn De Morgan, Night and Sleep, 1878 ( The De Morgan Centre, London/Bridgeman ArtLibrary International)

v3.1

To Catherine and Alexander

Contents

Preface

This is the most personal book I have written, personal in ways I had not anticipated. For close to three decades I have been teaching a large undergraduate class called Rites of Passage. In this course I deal with coming-of-age narratives from medieval France up to our own moment, using a mix of famous writers such as Twain and Faulkner, along with other, less known favorites of mine, such as Tarjei Vesaass The Ice Palace. One of my chief reasons for teaching this course is to urge students to realize that their own experience of growing up issurprisingly, rewardinglymirrored in books from other times, other places. Exploring such texts with students is gratifying, for they easily see that their own college experience is itself a rite of passage.

Therefore, when I set out to write a book on two major phases of lifegrowing up and growing oldI figured it would be easy enough to make use of my teaching for the growing-up part, while finding the appropriate books about aging to use as the second part of the diptych. I had never worked with students on issues of growing olda nonstarter topic, if ever there was onebut I felt confident that I could make a judicious selection of literary materials dealing with that topic, to create a balanced study. This was going to be fun, I felt.

What I failed to realize was the impress of passing time on myself. During the several years I have spent writing this book, I have moved, at a surprising speed, into the territory of old age. And I began to realize that these literary matters were disturbingly existential for me, that I was in effect doing my own crash course in learning about the challenges, travails, surprises, and (hopefully) rewards of growing old. At the far side of this book now, I am a rather different person than I was when I first envisaged this study: closer to retirement, more aware of physical decline, more attuned to my own gathering exit from much I had taken for granted, more certain that I (like peers my age) am increasingly engaged in dodging bullets. My vision has changed. I now see growing up as something far more precious and exposed, more vulnerable and fateful, than I did in the confident, breezy courses I have taught on this topic over the years. And I now feel the awful weight of Freuds words on King Lear: making friends with the necessity of dying. There is little that is strictly literary in all this.

But literature is what I know best. And I realized that my most intimate feelings about these key matters of entry and exit nonetheless have their source in literature. And, of course, that is what I am arguing in this book: that literature shows us who we are; it never stops doing this. Ive posited this view before, but never with quite the personal conviction that youll see in the pages ahead. This (very likely valedictory) book also constitutes something of a conclusion to my career. The ground I coverfrom Sophocles and Shakespeare to Art Spiegelman and Jonathan Safran Foerrepresents pretty much a roll call of the works of literature Ive dealt with over a lifetime, but I now understand that they illuminate my own lifetime. And the personal voice Ive allowed myself throughout this book is a voice that finds both its matter and its manner, its substance and its timbre, in the books I love. I mean this quite literally: literature frees my tongue and imagination, liberates and creates my best thinking, brings to the fore whatever gift I may have, and is arguably what is most social as well as most private about me. Literature, a term derived from the Latin for letters, feeds my own letter to the world. I have lived a life of privilege in the academyworking year after year with the ever young as I move through timeand this is my way of repaying the debt I owe to the great writers of then and now. At this late stage of my life, it feels like the right thing to do.

INTRODUCTION

The Riddle of the Sphinx

What is the creature that is on four legs in the morning, two legs at noon, three legs at night? Oedipus answers, Man. He wins the prize, becomes king, and marries the queen, all because he understood the riddle. It is a story we think we too understand. Four legs means crawling infant; two legs means erect and upright at ones prime; three legs means leaning on a staff or crutch or family member in old age. Man would be the creature whose legs vary in number, whose very locomotion alters, whose hardwired metamorphoses are governed by planetary rules: a morning phase, an evening phase. Only Homo sapiens goes through these transformations. Other species grow up and grow old, but they leave no record of what they encountered.

Oedipus does not say time; he does not say story. Yet that is what the riddle actually signifies: the trip through time, the universal human voyage from morning to noon, from noon to night. Oedipuss own dark fate lies coiled, concealed, in just those passages. So, too, does our own. The human story is rich in testimony about these two central transformations, growing up and growing old, that script so much: not just our lives but our notions about education, love, maturation, wisdom. Here is the trajectory from innocence to experience, the entry/exit scheme, that frames all life. My book takes its lessons from the Sphinx, to explore these fundamental and fateful passages. How much do we actually know about these crucial chapters of our existence? Is your own story a riddle?

On the Move

Our past grows every moment we liveProust beautifully said that we live on stilts, stilts that get longer each day of our life, stilts from which we must eventually fallbut it also grows further away, seems at once haunting and unreal. We ask: Was that I? Are those scrapbook images real? I know they are accurate, would pass muster in a courtroom, but are they real? Can I still feel the pulsing life in those frozen images? Old men ought to be explorers, still and still moving, wrote T. S. Eliot. As I move toward my end stage, what purchase can I possibly have on my beginning, my formation? Prousts legendary account of a tired and depressed middle-aged man dipping a pastry, a madeleine, into a teacup and recoveringshimmering, alive, deep inside him but now rising anew, bathed in the air of long agohis childhood: this beautiful version of retrieval has eluded me personally for some time now, and I fear it may be the same for many of my readers.