Table of Contents

To Ann, again

PREFACE

I am frequently asked by students and friends: Do you ever write novels? I have always taken it as a compliment, as a recognition that what I do with literature has some kinship with fiction itself, rather than being straightforward literary criticism. But I have always answered: No, I dont write novels. And I sometimes add, by way of confession: My relation to art is parasitic I take from it, I feed on it, but I dont create it. This usually concludes the conversation.

I always said no, because I understood the question in relation to my biography: childhood in Memphis, Tennessee, in the forties and fifties, college and graduate school at Princeton and Harvard, study in France and Germany, marriage to a Swedish woman, career at Brown University, making of a family of children, and now grandchildren, over the long years. Those are the facts of my life. No, I have not elected to write directly, or even indirectly, about that, to transpose that into fiction. I am a professor, not a novelist.

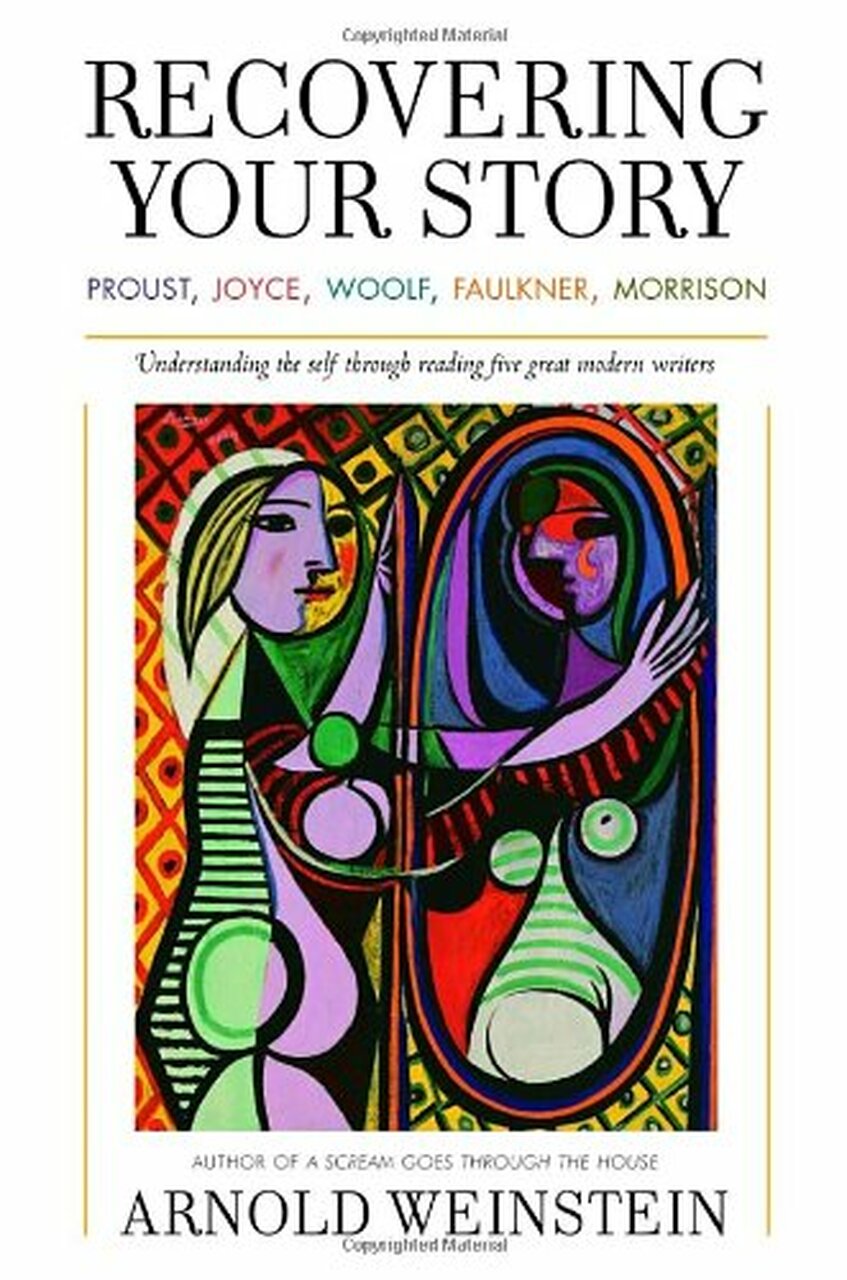

But are things this simple? It occurs to mevery late in the game, reflecting on this book Ive written, and close to the end of my careerthat perhaps I do write novels, that Recovering Your Story is, in ways I neither foresaw nor intended, a novel, my novel, my story. I need great books, have always needed them, for it is in these novels (that I read and teach and write about) that I find my own voice.

In one sense, this has to do with my central argument in the pages ahead. At the center of this long book about long books is a simple truth: We want to recover our story. The simple part is: our storythe melody of our felt lifeis what most eludes us, since it is not to be found in mirrors or scrapbooks or diaries or rsums or even in our immediate thoughts. So, where is it? In novels, I claim, especially in Modernist fiction. These groundbreaking narratives seek to uncover the actual shape and texture of a life: its temporal strata of past and present and conditional, its spatial parameters that chart person and place, but alsocruciallyits inside testimony of consciousness, as the inner noise we make while going through the world and processing life.

These matters are, however, no longer simple at all; in fact they can only be transcribed or conveyed or created by a writing that is attuned to both psyche and event, to private landscape and public stage. Such is the writing in Proust, Joyce, Woolf, Faulkner, and Morrison; it stuns and dazzles us with its vistas and purview, with its mixed levels of reality, with its radical break from traditional notation. These five authors reinvent the novel by exploding our sense of what we are. I want my book to send you into theirs.

But my book plays by the rules (which theirs break). It is a guidebook of sorts, a personal tour of these rich and varied fictional worlds, and it is meant to open them up, to make you realize how intimate and hospitable and mirrorlike they arerather than how daunting or inaccessible they may appear. Needless to say, then, my own prose could hardly be as emancipated and glorious as that of the books we are discussing.

And yet, in looking back at what I have writtenthat is what prefaces do: They are the authors last word, even if they are your first wordsI find that I have indeed limned my own story in this book. In some instances this is quite evident: I do not step back from personal commentary (is there any other kind?), and I occasionally speak of the events of my own life as I first read these authors, or as I now see them. I find myself a player in this book.

Thus, the readings you will encounter are themselves longitudinal, and in ways I had not fully anticipated. I have graphed, quite unintentionally, my own four and a half decades of conversance with Proust, Joyce, Woolf, and Faulkner, as well as a briefer but still substantial involvement with Morrison covering close to twenty years. The sheer number of hours I have spent in their company, when I actually go about tallying it, is enough to give me serious pause concerning my priorities. What I never imagined was the human curve and consequences of this literary acquaintanceship.

You will of course see these pages as unfurling commentary, taking place on one plane. But I see them as a history, as an almost lifelong series of relationships, arguably among the deepest and most nuanced relationships that I know how to create and sustain and enjoy. It is not merely that I reflect back on my various readings of these wonderful books, but rather the opposite: These books send me back to my earlier engagements with them, to earlier selves, to an entire conversation evolving over time, consisting of thirty-five years of lecturing on these figures, as well as positions I have taken on them, in print, from college essays to my doctoral thesis to articles and books I have written. Not to mention the vast amount of mental and emotional noise about these five writers, still sounding in my brain. Faulkners Quentin Compson describes himself as a barracks filled with stubborn... ghosts, and I suspect that these books inhabit me along just those vampirish lines.

But this is my novel for other, perhaps deeper reasons. I realize ever more clearly that these novels tell my story as much as I tell theirs. My life and my thinkingas professor, as person, as sentient beingare inextricably, even frighteningly intertwined with their work. Their views about life and death and love and memory and the purposes of art are threaded into my existence, far beyond my capacity to sort it all out. In delving as deeply as I knew how, throughout my adult life as well as during the writing of this book, into the rich work of Proust, Joyce, Woolf, Faulkner, and Morrison, I have been stealing riches for a lifetime, stealing them by dint of internalizing them and furnishing my own mind and heart with their words and visions.

Let me rephrase this: If you ask what is on the inside and the central claim of my study is that these great writers depict our inner life as no one else has ever donemy own answer, at least in part, is these books. I grasp life through the prisms and lenses offered by these books (and, yes, others), prisms and lenses that I have quite simply adopted and incorporated into my way of seeing. None of this was done intentionally, but that means it was done even more profoundly and invisibly. Writing about them now has brought the extent of this poaching to visibility. I make no apologies. On the contrary, I am proud to have rifled and pilfered and taken from their work. But I now recognize that they have stocked my house, fed my mind, nourished my heart, etched my vision, and layered my words in ways far more profound than I ever imagined.

A motif that comes up in my discussion of Morrisons Beloved is that of an umbilical cord, a vital conduit that connects us to our loved ones, existing well beyond the moment of birth and the apparent severing of the cord; it is clear to me that these five authors live in me in that fashion. How, then, can I be surprised that these writers speak me every bit as much as I speak them? In writing this book, in reflecting consciously on the personal hold these novels have on me, I have wanted to make that special conversation between them and me, between book and readeraudible. Books live in this way. Better still, writing this book has been my way of continuing the exchange, of perhaps giving back something of my own after having taken so much.

Next page