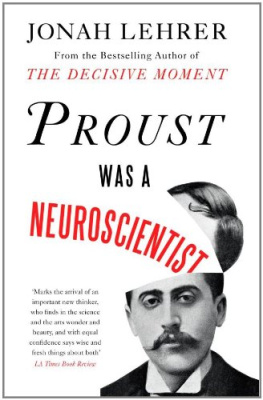

Lehrer - Proust Was a Neuroscientist

Here you can read online Lehrer - Proust Was a Neuroscientist full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Boston, year: 2008, publisher: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Proust Was a Neuroscientist: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Proust Was a Neuroscientist" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Lehrer: author's other books

Who wrote Proust Was a Neuroscientist? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Proust Was a Neuroscientist — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Proust Was a Neuroscientist" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

BOSTON NEW YORK 2007

Copyright 2007 by Jonah Lehrer

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections

from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lehrer, Jonah.

Proust was a neuroscientist / Jonah Lehrer.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN -13: 978-0-618-62010-4

ISBN -10: 0-618-62010-9

1. Neurosciences and the arts.

2. NeurosciencesHistory. I. Title.

NX 180. N 48 L 44 2007 700.1'05dc22 2007008518

Printed in the United States of America

Book design by Robert Overholtzer

MP 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PHOTO CREDITS : , Courtesy of the Oscar Lion Collection, Rare

Books Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden

Foundations; , Courtesy of the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg

Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public

Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations; , Courtesy of

Image Select/Art Resource, New York; , Courtesy Erich Lessing/Art

Resource, New York; ,

Courtesy of Muse d'Orsay/Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York;

, Courtesy of Galerie Beyeler/Bridgeman-Giraudon/Art Resource,

New York; , Courtesy Leopold Stokowski Collection of Conducting

Scores, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania;

, Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (47.106);

, Courtesy of the New York Public Library/Art Resource, New

York; , Courtesy British Library/HIP/Art Resource, New York

For Sarah and Ariella

PRELUDE

1. Walt Whitman

The Substance of Feeling

2. George Eliot

The Biology of Freedom

3. Auguste Escoffier

The Essence of Taste

4. Marcel Proust

The Method of Memory

5. Paul Czanne

The Process of Sight

6. Igor Stravinsky

The Source of Music

7. Gertrude Stein

The Structure of Language

8. Virginia Woolf

The Emergent Self

Coda

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

Reality is a product of the most august imagination.

Wallace Stevens

This systematic denial on science's part of personality

as a condition of events, this rigorous belief that in its

own essential and innermost nature our world is a strictly

impersonal world, may, conceivably, as the whirligig of

time goes round, prove to be the very defect that our

descendants will be most surprised at in our own boasted

science, the omission that to their eyes will most tend

to make it look perspectiveless and short.

William James

I used to work in a neuroscience lab. We were trying to figure out how the mind remembers, how a collection of cells can encapsulate our past. I was just a lab technician, and most of my day was spent performing the strange verbs of bench science: amplifying, vortexing, pipetting, sequencing, digesting, and so on. It was simple manual labor, but the work felt profound. Mysteries were distilled into minor questions, and if my experiments didn't fail, I ended up with an answer. The truth seemed to slowly accumulate, like dust.

At the same time, I began reading Proust. I would often bring my copy of Swann's Way into the lab and read a few pages while waiting for an experiment to finish. All I expected from Proust was a little entertainment, or perhaps an education in the art of constructing sentences. For me, his story about one man's memory was simply that: a story. It was a work of fiction, the opposite of scientific fact.

But once I got past the jarring contrast of formsmy science spoke in acronyms, while Proust preferred meandering proseI began to see a surprising convergence. The novelist had predicted my experiments. Proust and neuroscience shared a vision of how our memory works. If you listened closely, they were actually saying the same thing.

This book is about artists who anticipated the discoveries of neuroscience. It is about writers and painters and composers who discovered truths about the human mindreal, tangible truthsthat science is only now rediscovering. Their imaginations foretold the facts of the future.

Of course, this isn't the way knowledge is supposed to advance. Artists weave us pretty tales, while scientists objectively describe the universe. In the impenetrable prose of the scientific paper, we imagine a perfect reflection of reality. One day, we assume, science will solve everything.

In this book, I try to tell a different story. Although these artists witnessed the birth of modern scienceWhitman and Eliot contemplated Darwin, Proust and Woolf admired Einsteinthey never stopped believing in the necessity of art. As scientists were beginning to separate thoughts into their anatomical parts, these artists wanted to understand consciousness from the inside. Our truth, they said, must begin with us, with what reality feels like.

Each of these artists had a peculiar method. Marcel Proust spent all day in bed, ruminating on his past. Paul Czanne would stare at an apple for hours. Auguste Escoffier was just trying to please his customers. Igor Stravinsky was trying not to please his customers. Gertrude Stein liked to play with words. But despite their technical differences, all of these artists shared an abiding interest in human experience. Their creations were acts of exploration, ways of grappling with the mysteries they couldn't understand.

These artists lived in an age of anxiety. By the middle of the nineteenth century, as technology usurped romanticism, the essence of human nature was being questioned. Thanks to the distressing discoveries of science, the immortal soul was dead. Man was a monkey, not a fallen angel. In the frantic search for new kinds of expression, artists came up with a new method: they looked in the mirror. (As Ralph Waldo Emerson declared, "The mind has become aware of itself.") This inward turn created art that was exquisitely self-conscious; its subject was our psychology.

The birth of modern art was messy. The public wasn't accustomed to free-verse poems or abstract paintings or plotless novels. Art was supposed to be pretty or entertaining, preferably both. It was supposed to tell us stories about the world, to give us life as it should be, or could be. Reality was hard, and art was our escape. But the modernists refused to give us what we wanted. In a move of stunning arrogance and ambition, they tried to invent fictions that told the truth. Although their art was difficult, they aspired to transparency: in the forms and fractures of their work, they wanted us to see ourselves.

The eight artists in this book are not the only people who tried to understand the mind. I have chosen them because their art proved to be the most accurate, because they most explicitly anticipated our science. Nevertheless, the originality of these artists was influenced by a diverse range of other thinkers. Whitman was inspired by Emerson, Proust imbibed Bergson, Czanne studied Pissarro, and Woolf was emboldened by Joyce. I have attempted to sketch the intellectual atmosphere that shaped their creative process, to highlight the people and ideas from which their art emerged.

One of the most important influences on all of these artistsand the only influence they all sharedwas the science of their time. Long before C. P. Snow mourned the sad separation of our two cultures, Whitman was busy studying brain anatomy textbooks and watching gruesome surgeries, George Eliot was reading Darwin and James Clerk Maxwell, Stein was conducting psychology experiments in William James's lab, and Woolf was learning about the biology of mental illness. It is impossible to understand their art without taking into account its relationship to science.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Proust Was a Neuroscientist»

Look at similar books to Proust Was a Neuroscientist. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Proust Was a Neuroscientist and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.