CONTENTS

Introduction

by Twigs Way

The One & All Garden Books were produced by the London branch of the Agricultural and Horticultural Association in the first decade of the twentieth century, and sold for a penny. Edited by the social reformer Edward Owen Greening (1836 1923), they arose out of the working class cooperative movements that sought to better the life of the rural and urban labourer and his family. The association originally founded in the mid-nineteenth century, and counting the art critic John Ruskin amongst its founders claimed to circulate three million publications every year, and to sell, at a minimal profit, fifteen million packets of cheap reliable seeds, bearing clear cultural directions. What profits were made were invested back into schemes for public benefit, including the founding of local horticultural associations. Greening, who was himself a Fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society, commissioned the foremost garden writers of the period to pen a series of booklets on the most popular gardening topics of the period. Starting with Sweet Peas, at the time perhaps the most popular garden flower of the working classes, the series grew to include forty booklets ranging across topics from allotments and antirrhinums to weather and window gardens. Each booklet was sold for one penny or, for five shillings a year, a subscriber could be sent all the publications as well as samples of seeds, fertilisers etc, which were also produced and sold by the Association. The popularity of the series is attested by the reprinting of several editions of some of the topics Perennials (booklet No. 5), for example, went to at least five editions, and Asters reached six editions, indicating sales of both in the region of 200,000 copies (around 40,000 copies were generally made of a first edition).

Topics covered by the booklets give an insight into both the central concerns of the Association and the social and horticultural context of the period, as well as reflecting the fashion in plants and planting styles. Food production for the family runs through several of the booklets, whether on the allotment or in the garden, and as well as individual booklets on these subjects a special two-part booklet dealt with the planting and cropping of allotments generally. Reference was made to the allotment movement that was still at that date trying to ensure provision for all, as well as provision of allotment plots for gardeners and soldiers close to barracks. Many of the booklets refer to the growing urbanisation of the early twentieth century: tackling problems with small gardens, shady lawns, small greenhouses (an aspiration for many) or, for the most restricted, window gardens, indoor gardens, and even the growing of mushrooms in cellars. From 1893 onwards Greening himself lived in Lewisham (South London), and he brought to bear his own experience in several of the topics. Shady Gardens, for example, included an image of the editors garden, although rather larger in scale than the narrow back garden of a terraced house shown on the previous page in the same publication.

The coming of the electric trams allowing people to move away from the slums, the creation of pretty garden suburbs for the middle classes, and to a lesser extent garden cities for labourers at the new manufactories, were all cited as playing their part in the rise of gardening for all. Into the small spaces allotted to the working- and even middle-class gardener were packed the most popular flowers of the day, often planted not only for their cheering influence but also for competition in the popular shows that sprung up in both rural and urban areas. Phlox, pansies, carnations, annual or China asters, antirrhinums, stocks, and sweet peas each had a booklet to themselves, whilst other more general booklets dealt with annuals (popular because of their cheapness), climbers and perennials. For the more adventurous rockeries, ferneries and even grottoes, could be created, and hints were given on layout and design.

In the pages of the One & All Garden Books gardening was to be societys salvation and Englands triumph. The English lawn is described as having a superiority which will ever remain unchallenged, the raising of perennials from seed as a hobby with ample room for the enterprising spirit, and the blossoming of window gardens an important act of local patriotism. The phraseology and approach are redolent of that moment in time when Victorian aspirations met with Edwardian achievement, that golden period before the First World War when the flower garden was to be cast aside and the growing of the nations food became a matter of heroism rather than an innocent hobby.

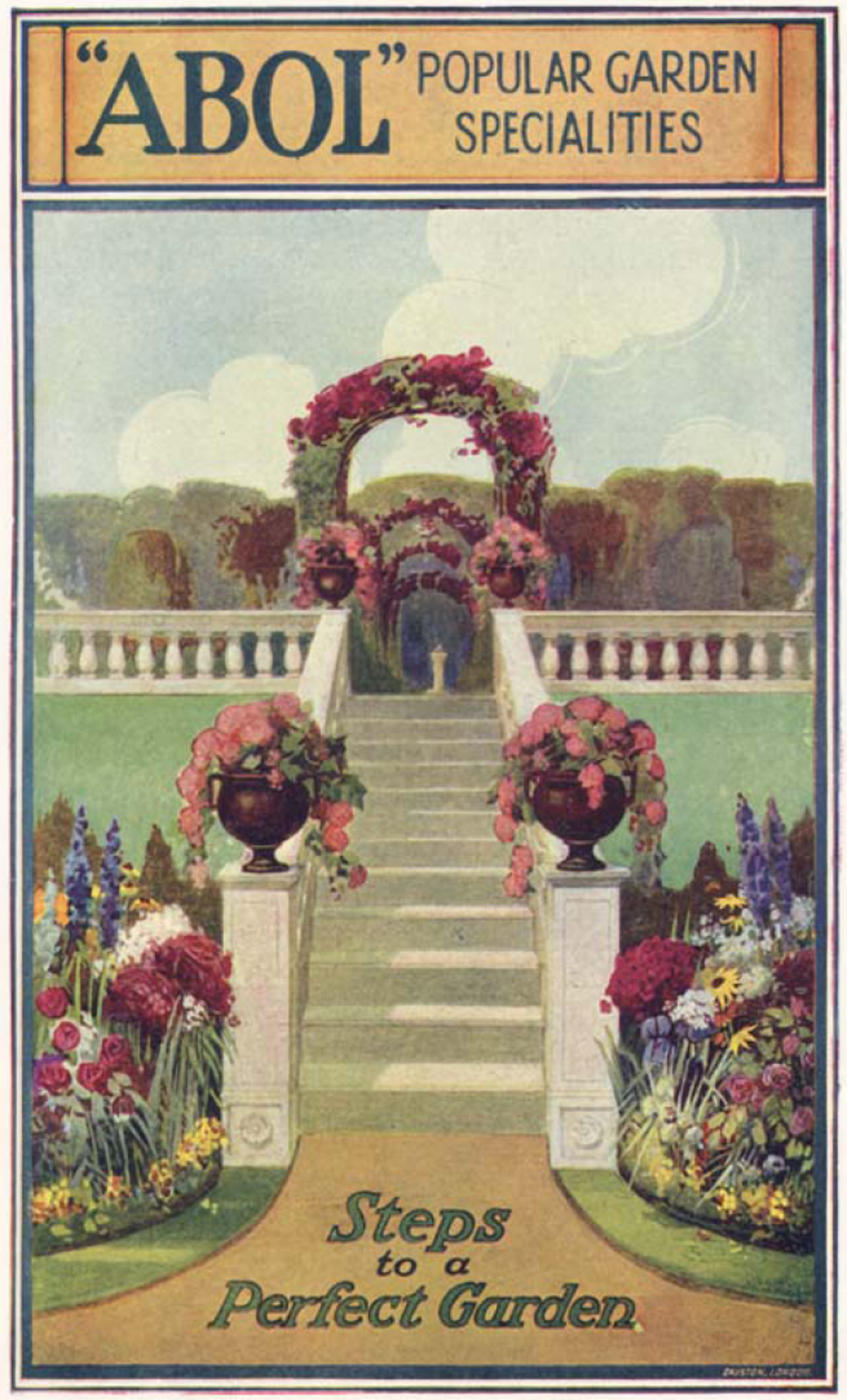

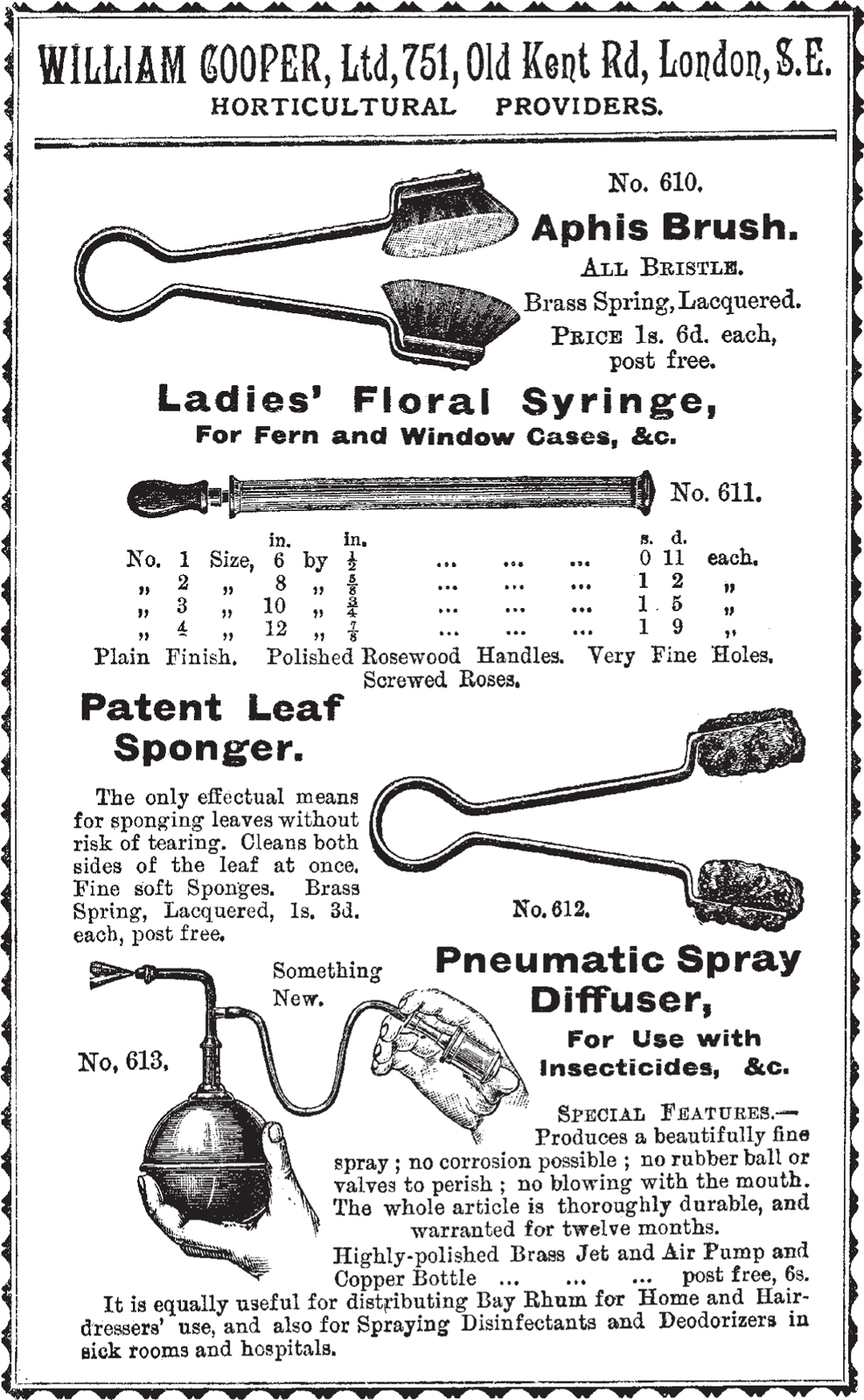

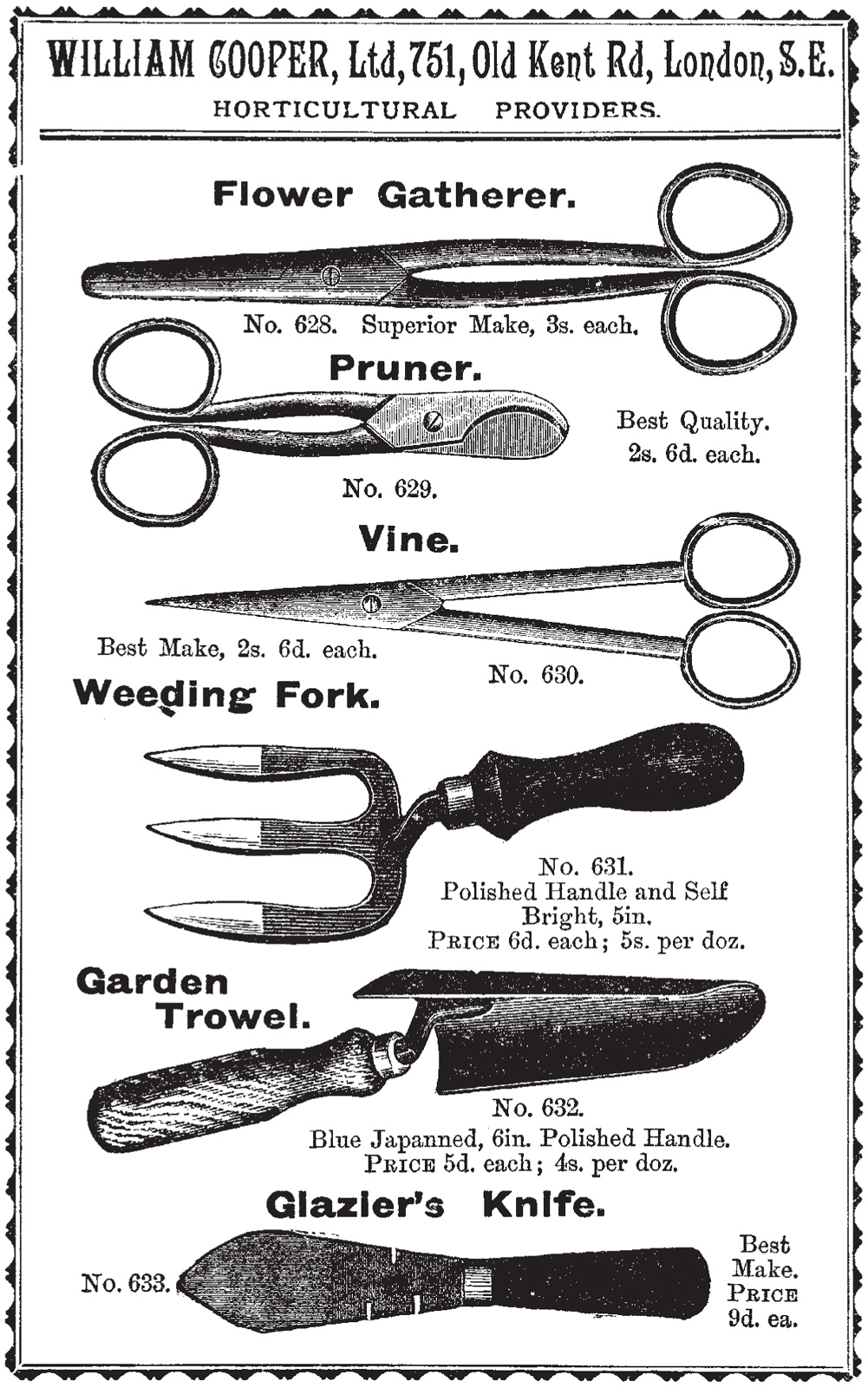

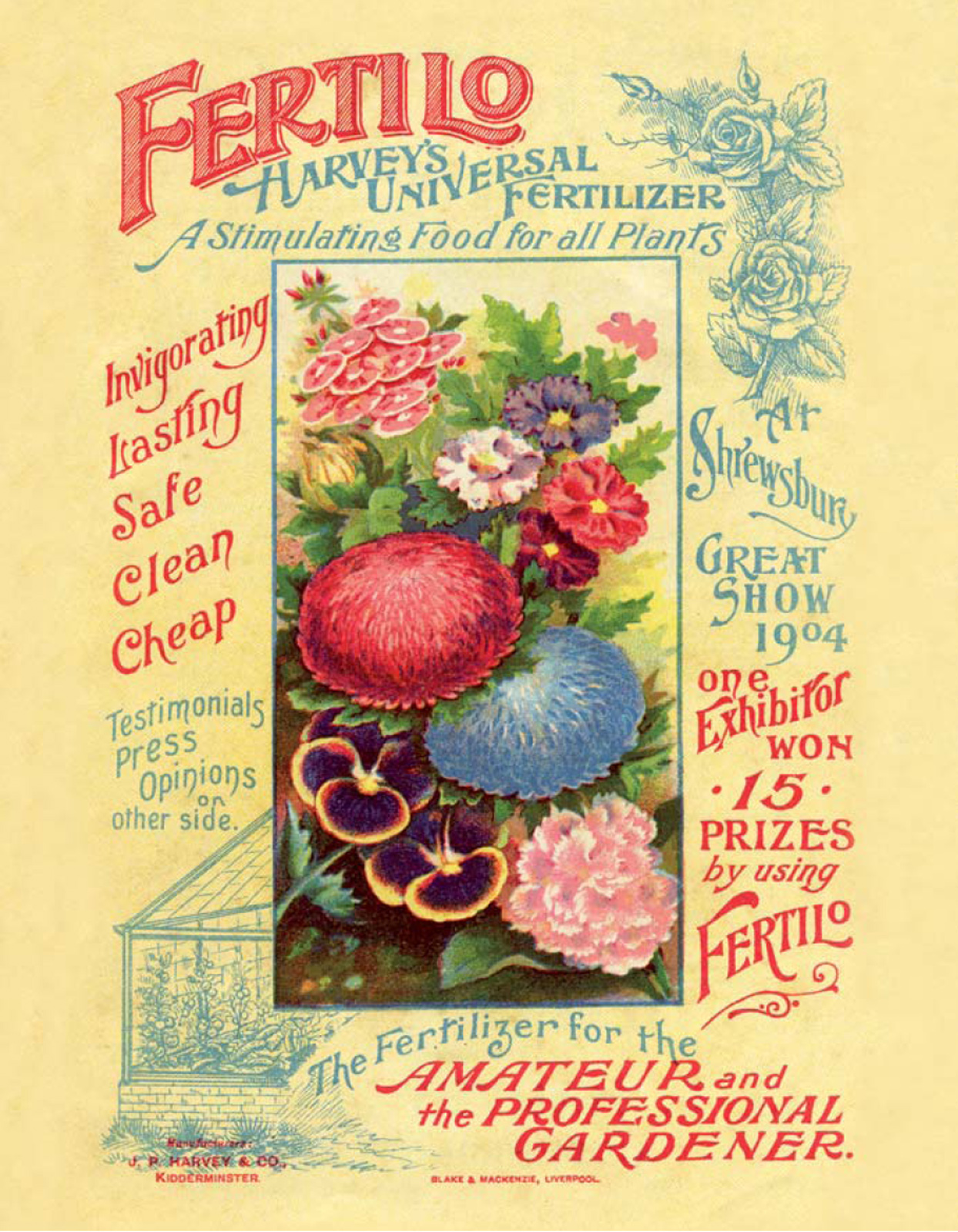

There is much that is familiar in the pages reproduced here from the original One & All booklets. Concern with soil preparation, planting times, the discouragement and extermination of pests, and the constant striving for the best of gardens despite the unpredictability of the English weather. But there is also much that is of the past. The use of soil fumigant to rid the lawn of worms by wholesale slaughter, the promotion of the popular Wardian case to enable fern culture in the gloomiest of early Edwardian living rooms, the ongoing fight for the right to an allotment, and of course the ease with which horse manure might be obtained by merely going out onto a busy street. Advertisements too evoke a world at once similar and strange: grass seed and plant labels, Bordeaux Mix, Pears Soap and Jeyes Fluid share pages with exhortations to take up fretwork as a fascinating evening hobby, invest in Canary Guano, smoke Players Cigarettes or spray concentrated nicotine through the greenhouse. The past may be a foreign country but for the gardener it is in many ways an instantly recognisable one.

NOTE: Some of the plants and chemicals recommended in the One & All books are no longer in use. Particular notice is drawn to the fact that it is illegal to plant (or spread in any way) Polygonum cuspidatum (Japanese Knotweed) and Impatiens glandulifera (Himalayan balsam). In addition, arsenic, nicotine sprays, and uncontrolled garden/allotment use of Jeyes Fluid, once all common pest control methods, are now illegal.

PART I

Types of Garden

PART I

Types of Garden

In the modern imagination the Edwardian garden is one of expansive lawns, overflowing borders and rich shrubberies. But in reality the vast majority of gardens were small, belonging to the newly suburbanised middle and working classes. In the booklet on Small Gardens (No. 26 in the series) these are defined as anything from 10 feet wide and 20-30 feet long up to the rarer quarter of an acre. In these gardens flower borders had to be crimped to between a foot long and four foot wide, and the confining fences and walls formed a constant backdrop. Strict economy dictated use of clinker or flints as edging, with larger broken bricks for paths or a simple rockery. Despite these restrictions a mix of annuals and perennials (all grown from the One & All seed supplies) could create a suburban paradise, supplemented with hanging baskets, window boxes and trellises. Shade was no limiter of such endeavours, with recommendations for suitable plants, including the ever-popular ferny grot and more invasive garden plants, such as Japanese knotweed (now banned). Lawns were only suitable for the medium sized garden, but here lavish attention was paid to their cultivation. A lawn mowing machine was only used after good growth had been established, and previous to that the old-fashioned scythe was still recommended. Rolling should be frequent and ill weeds had no place on an English lawn! Perhaps the most fascinating in this section however are the recommendations and illustrations for the window gardens and indoor gardens which were so beloved in an age when backyards had frequently to be given over to the coal house and the outdoor privy. These gardens also had a special meaning for the indwellers of the house: in the words of Greening, the wife and daughters, tied much indoors by the endless engrossing cares of house duties, or the invalid, trapped in a sunless room. Even a pot of ivy in the hearth, or an acorn grown in a bottle, would bring cheer. The lack of sunlight in such rooms must in some cases have been brought about by the effusive window boxes, the scale and magnificence of which threatened to totally obscure the actual window. Trailing nasturtium combined with tall stocks, bushy pelargonium, petunias and the popular tropaeolum created masses of foliage, which not only added beauty to the dwellings and pleasure to the inhabitants but, as the writer optimistically claimed, led to increased commercial prosperity of entire areas.

CONTENTS

CONTENTS