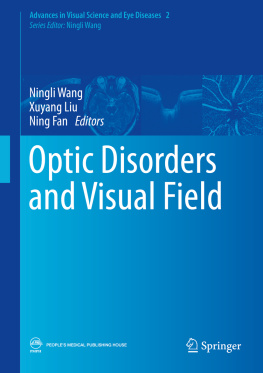

Visual Ecology

Visual Ecology

Thomas W. Cronin, Snke Johnsen,

N. Justin Marshall, and Eric J. Warrant

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2014 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

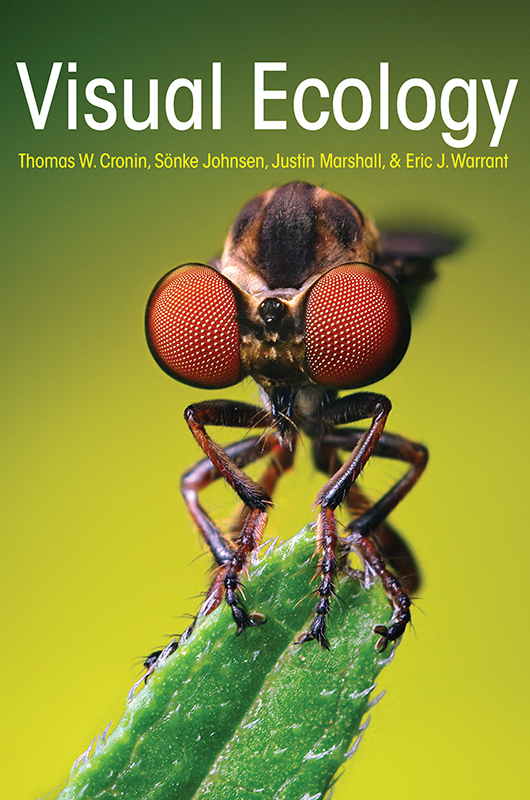

Photograph of robber fly (Holcocephala sp.) Thomas Shahan

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cronin, Thomas W., 1945

Visual ecology / Thomas W. Cronin, Sonke Johnsen, N. Justin Marshall, and Eric J. Warrant.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15184-7 (hardcover)

1. Vision. 2. Animal ecology. 3. Physiology, Comparative. 4. EyeEvolution. I. Title.

QP475.C76 2014

612.8'4dc23

2014002359

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To John Lythgoe and William Mac McFarland,

two greatly missed pioneers in visual ecology

Contents

Illustrations

Preface

We humans are visual creatures. We are also introspective and curious, a combination that makes us all by nature amateur visual ecologists (even if we dont know it). Because our world is dominated by visual sensations, we naturally wonder how other animals see their particular worlds. When a cat is entranced by images of fish on a television screen, does it see their colors? Does it think they are real fish? What is it experiencing? When a wasp flies up and stares us in the face, just what is it seeing? These questions have probably been asked for as long as our species has been around. The third-century Roman philosopher Plotinus stated the fundamental principle of visual ecology nearly two millennia ago: To any vision must be brought an eye adapted to what is to be seen, and bearing some likeness to it.

Still, the study of visual ecology didnt come into its own until near the end of the twentieth century. Researchers such as John Lythgoe in England and Bill Mac McFarland in the United States, to whom we have dedicated this book, first used the term visual ecology to describe their research on animal visual systems in nature. In 1979, Lythgoe published a smallish book titled The Ecology of Vision. The book introduced a new way of thinking about animal vision, relating the huge evolutionary diversity of visual systems to the environments inhabited by particular animals. Lythgoe presented unifying principles that involved several fieldsvisual optics, environmental radiometry, retinal physiology, visual aspects of behavior, and numerous othersthat had historically been considered as separate.

Lythgoe, McFarland, and a few others like them made up the scientific generation who seeded the field, and the authors of this book were inspired as graduate students and young scientists by their elegant work and their personal charm. The four of us typify the field. Were international. Our home laboratories are in the United States, Sweden, and Australia, but we all consider the planet our field site and the animal kingdom our model organism. We spend time on ships, in woods and rainforests, in deserts, and in marshes, muddy waters, and coral reefs; we work in daylight, moonlight, starlight, and in the black depths of the worlds oceans; our field sites cover six of the seven continents (and we envy the lucky few visual ecologists who have made it to Antarctica!).

Perhaps most importantly for the writing of this book, we are friends. We have known each other for decades, visited each others home laboratories and actual homes, worked on the same teams in the field, published together, attended international meetings together, and shared long evenings in bars. Again characterizing the field as a whole, we really enjoy each others company, and despite our natural competitiveness as scientists, we readily share our ideas, data, and students. We like each other, and that has gotten us through the difficulties that necessarily arise in a multiauthor project such as writing a book like this. We got a lot of pleasure out of just sitting back in an armchair to read each others contributionsand equally much pleasure from constructively criticizing them!

Naturally, an effort like this involves many, many more souls than just the four of us. Laura Bagge, Jamie Baldwin, Nicholas Brandley, Mike Bok, Karen Carleton, Jon Cohen, Kate Feller, Yakir Gagnon, Alex Gunderson, Elizabeth Knowlton, Dan Speiser, Cynthia Tedore, Kate Thomas, and Jochen Zeil read our chapter drafts. Tammy Frank, Ron Douglas, and an anonymous reviewer read and critiqued the entire manuscript. Judy Rubin contributed to the artwork, and we benefited from the graphic and photographic contributions of dozens of colleagues and associates. The team at Princeton University Press, especially our senior editor Alison Kalett, our editorial associate Quinn Fusting, and our production editor Karen Carter helped keep us on track and calmly sorted our differences of opinion when they inevitably arose. The entire manuscript was expertly and thoroughly copyedited by Elissa Schiff. Our graduate students and the other members of our laboratories kept us motivated with their own curiosity, their drive to carry the field forward, and their interest in seeing the final product of our labors. We are particularly indebted to Marie Dacke, Almut Kelber, Mike Land, Ellis Loew, Dan-Eric Nilsson, David OCarroll, Jack Pettigrew, David Vaney, Rdiger Wehner, and Jochen Zeil for their inspiration and encouragement. Most of all, we thank our wives, Roselind, Lynn, Sue, and Sara, for support throughout the project. None of them card-carrying visual ecologists, they nevertheless stuck with us as we wrote this book and gracefully put up with our global wanderings and consuming passion for science.

Visual Ecology

Introduction

A tiny fruit fly, hardly bigger than a speck of dust, drifts along the edge of a pond in the morning sunlight, keeping a constant course and height through the unpredictable buffeting of the morning breeze. Despite its minuscule size, its silhouette against the empty sky has betrayed the flys passage to an alert predator. A dragonfly perched on the pond side rises in a buzz of wings, aims to intersect the fruit flys path, and plucks it from the air in a graceful upward swoop. Returning to its perch to enjoy its catch, the dragonfly is spotted by a hovering kestrel far above; with a blur of motion, the kestrel snatches up the dragonfly and carries it to her home not far away. As the mother kestrel settles onto the edge of her nest, two tiny babies greet her arrival by stretching their necks upward. Tempted by her nestlings colorful, bobbing mouths, she tears up their breakfast and shoves a piece into each one.

Each of these creatures was guided by its eyes as it carried out its accustomed behaviorsthe fruit fly heading steadily toward its chosen destination; the dragonfly as it sighted the fly, computed its course, and snatched it from the sky; the kestrel as it picked out the dragonfly against the tangle of pondside vegetation and unerringly plucked it from its perch; the nestlings as they spotted their mothers familiar shape descending from the sky; and the kestrel again as it responded to their irresistible opened mouths. Each animals eyes allowed it to execute the behavior necessary for its survival (although, admittedly, not all survived this quiet morning). How do these various visual systems function? How is it that the fruit fly was so beautifully adapted for visual control of flight in air that buffeted its minuscule body? What allowed the dragonfly to see such a tiny spot in the sky, to recognize it as nearby prey and not a bird passing far above, and to derive the geometry required to intercept it? How could the kestrel see a blue, toothpick-sized form against masses of green vegetation from so far above? Why were its babies mouths so attractive? For that matter, how was it that the fruit fly never spotted the approaching dragonfly, and what allowed the dragonfly to see the speck of a passing fly while missing the predatory stoop of the kestrel? These are the kinds of questions that are addressed in the field of visual ecology.

Next page