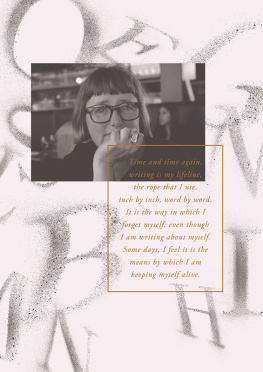

The

Iceberg

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2014 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Marion Coutts, 2014

The moral right of Marion Coutts to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 9781782393504

E-book ISBN: 9781782393511

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Let it Go by William Empson reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown Group Ltd, London on behalf of The Estate of William Empson. Copyright William Empson 1949.

Let It Go

It is this deep blankness is the real thing strange.

The more things happen to you the more you cant

Tell or remember even what they were.

The contradictions cover such a range.

The talk would talk and go so far aslant.

You dont want madhouse and the whole thing there.

William Empson

Contents

SECTION 1

1.1

A book about the future must be written in advance. Later I wont have the energy to speak. So I will do it now.

The others are near. I can touch them, call them to me and they are here. We are all here, Tom, my husband, and Ev, our child. Tom is his real name and Ev is not really called Ev but Ev means him. He is eighteen months old and still so fluid that to identify him is futile. We will all be changed by this. He the most.

The home is the arena for our tri-part drama: the set for everything that occurs in the main. We go out, in fact all the time, yet this is where we are most relaxed. This is the place where you will find us most ourselves.

Something has happened. A piece of news. We have had a diagnosis that has the status of an event. The news makes a rupture with what went before: clean, complete and total save in one respect. It seems that after the event, the decision we make is to remain. Our unit stands. This alone will not save us but whenever we look, it is the case. The decision is joint and tacit and I am surprised to realise this. Though we talked about countless things talk is all we ever do we did not address it directly. So not a decision then, more a mode, arrived at together.

The news is given verbally. We learn something. We are mortal. You might say you know this but you dont. The news falls neatly between one moment and another. You would not think there was a gap for such a thing. You would not think there was room. The threat has two aspects: a current fact and an obscure outcome the manifestation of the fact. The first is immediate and the second talks of duration. The fact has coherent force and nothing, no person or thought or thing, escapes its shift. It is as if a new physical law has been described for us bespoke: absolute as all the others are, yet terrifyingly casual. It is a law of perception. It says, You will lose everything that catches your eye. Under this illumination there is no downtime and no off-gaze. For its duration, looking can never be idle. Seeing is active: it is an action like aiming or hitting.

Yet afterwards more strangeness we carry on in many ways as before, but crosswise to what might be expected, we are not plunged into night. It is still day, but the light is unnatural. The glare on daily life is blinding. Everything is equally illumined, without shade.

These are early days. Our house becomes porous. I am high and bleached and whited out. We are air and the walls are air. On hearing the news, our instinct is to tell it. Once known it cannot be unlearned; once told, not rescinded. So we start to speak, and the family, we three, are dissolved in fluid and drunk up by others. People appear, they come and go. They are always to hand. Ev is in his element and we are in ours. As I say, these are early days. Maybe it will always be like this.

1.2

It is Evs first day at the childminders. I arrive at nine, anxious and grave and trying not to show it. This is our first official separation. The mother of one is a volatile mix of niche knowledge and inexperience. I am a zealot. I have rolls of data to proclaim about his protocols: his beaker, when he likes to nap, his poo, his play, his pleasures, the snacks that are allowed and the snacks that are forbidden. I am not going to let anything stop me.

The childminder lives around the corner. She is much younger than me and canny. She has heard all this before. She knows to be patient and let me play myself out. When I am done, she will take the child. I eye her up and scan the house for flaws as I recite my speech. Is that a very sharp edge? That stair-gate looks shaky. The kitchen could be tidier. I know she has dogs; where are they? Why am I putting him in a house with dogs? We both understand that my rhetoric is symbolic, the words a verse-chorus lament to mark the movement of the child out of my orbit and into another: out of the home and into the world.

In mid-song I am interrupted. Tom arrives. I am surprised to see him and pleased. Lately we have been seriously upended. A week ago, while we were staying at the house of friends, he had a fit. We dont know why. He never had one before and the shock took us straight into hospital in the night. In the wake of this we have been unnerved, though slowly calming as he has been fine since and anyway, there is Ev to think about. Soon we expect some test results from the hospital. I imagine a letter about high blood pressure or diet, some readily managed condition, normal, nothing beyond us, nothing outwith the stretch of mid-life or span of circumstance. If you were to ask me, thats what I would say. But really I am not imagining anything. I am thinking about Ev.

Tom greets me directly and takes my sleeve, pulling Ev and me out of the yard away from the toys and into the street. Its good he is here. He recognises the importance of my mission and is come in solidarity to support me. I am an airship on its maiden voyage packed with mother adrenalin. The band is playing. Ascent is the most dangerous moment. I have already left the ground, my skin taut with the child and his real and imagined needs. The three of us cluster a couple of doors down alongside a white house with a low lilac wall. Number 36. Alpines, succulents and tiny sedum rooted in the shallowest scattering of earth are planted in gaps along its brickwork. Ev wriggles in my arms and I am still talking. Ev is so relaxed. He likes her. He will be happy here. Tom stops me. He says he has had a phone call. He has a brain tumour. It is very likely malignant.

Did I understand it before I heard it or did he finish the sentence before I understood? Conflagration: my ship is exploded. A fireball. Tears fall as burning fuel. There is no time for anything to be saved. There is no time for anything to sink in. There is no time. The word is the deed. The deed is done before knowledge can release its meaning. It is the quickest poison.

Next page