Dover Science Books for Children

FUN WITH SCIENCE. 46 ENTERTAINING DEMONSTRATIONS, George Barr. (0-486-28000-4)

SCIENCE RESEARCH EXPERIMENTS FOR YOUNG PEOPLE, George Barr. (0-486-26111-5)

ENTERTAINING SCIENCE EXPERIMENTS WITH EVERYDAY OBJECTS, Martin Gardner. (0-486-24201-3)

EXPERIMENTING WITH WATER, Robert Gardner. (0-486-43400-1)

SAFE AND SIMPLE ELECTRICAL EXPERIMENTS,

Rudolf F. Graf. (0-486-22950-5)

HUMAN ANATOMY IN FULL COLOR, John Green. (0-486-29065-4)

BIOLOGY EXPERIMENTS FOR CHILDREN, Ethel Hanauer (0-486-22032-X)

PHYSICS EXPERIMENTS FOR CHILDREN, Muriel Mandell. (0-486-22033-8)

HUMAN ANATOMY COLORING BOOK, Margaret Matt and Joe Ziemian. (0-486-24138-6)

CHFMISTRY EXPERIMENTS FOR CHILDREN, Virginia L. Mullin. (0-486-22031-1)

47 EASY-TO-DO CLASSIC SCIENCE EXPERIMENTS, Eugene F. Provenzo, Jr., and Asterie Baker Provenzo. (0-486-25856-4)

SCIENCE MAGIC TRICKS, Nathan Shalit. (0-486-40042-5)

CUP AND SAUCER CHEMISTRY, Nathan Shalit. (0-486-25997-8)

LIFE IN A TIDAL POOL, Alvin Silverstein and Virginia Silverstein. Illustrated by Pamela and Walter Carroll. (0-486-44592-5)

A WORLD IN A DROP OF WATER: EXPLORING WITH A MICROSCOPE, Alvin and Virginia Silverstein. (0-486-40381-5)

NATURES CHAMPIONS: THE BIGGEST, THE FASTEST, THE BEST, Alvin and Virginia Silverstein. (0-486-42888-5)

THE CODE OF LIFE, Alvin and Virginia Silverstein. (0-486-43944-5)

LIFE IN A BUCKET OF SOIL, Alvin and Virginia Silverstein. (0-486-41057-9)

SCIENCE EXPERIMENTS AND AMUSEMENTS FOR CHILDREN, Charles Vivian. (0-486-21856-2)

MY FIRST HUMAN BODY BOOK, Donald M. Silver and Patricia J Wynne. (0-486-46821-6)

See every Dover book in print at www.doverpublications.com

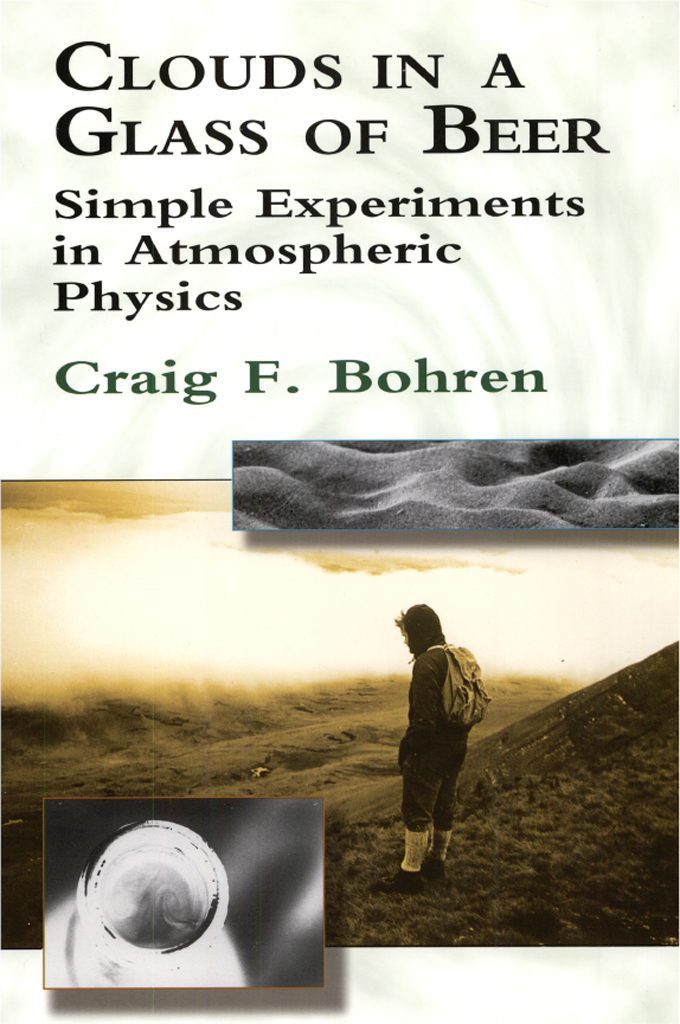

CLOUDS IN A GLASS OF BEER

CLOUDS IN A GLASS OF BEER

Simple Experiments in Atmospheric Physics

Craig F. Bohren

Foreword by

Jearl Walker

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Mineola, New York

Permissions

Bohren, Craig, Nonrandom Bubbles, Science, Vol. 216, #4547, p. 682 (Letters section), 14 May 1982. Copyright 1982 by the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Weather, Vol. 15, p. 245 (1960). Royal Meteorological Society, James Glaisher House, Grenville Place, Bracknell, Berkshire RG12 1BX.

DENNIS THE MENACE used by permission of Hank Ketcham and by North America Syndicate.

Laurens van der Post, Venture to the Interior, William Morrow & Co:, 105 Madison Ave, New York NY 10016.

Sydney Smith, Mostly Murder, first published in Great Britain 1959 by Harrap Ltd., 19-23 Ludgate Hill, London EC4M 7PD.

Copyright

Copyright 1987 by Craig F. Bohren

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2001, is an unabridged reprint of the 1987 edition published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bohren, Craig R, 1940-F.,

Clouds in a glass of beer : simple experiments in atmospheric physics / Craig F. Bohren ; foreword by Jearl Walker.Dover ed.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York : John Wiley & Sons, 1987.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-41738-7 (pbk.)

ISBN-10: 0-486-41738-7 (pbk.)

1. Atmospheric physics. 2. Atmospheric physicsExperiments. I. Title.

QC861.2.B64 2001

551.51dc21

2001028308

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

41738704

www.doverpublications.com

Dedicated to the memory of

Louis J. Battan.

This book would not have been written

had our paths never crossed.

Foreword

Suppose you had the opportunity of peering over the shoulder of Sherlock Holmes during an investigation. Imagine him examining what appears to be an ordinary scene. You and he see the same things, yet only he spots the clue that unravels the mystery.

Bohren is like Holmes in that he perceives mystery and puzzlement in what most of us would think is a common, uninteresting setting. You and he see the same things, but he notes the curious feature that unlocks some marvelous demonstration of scientific principles. This book gives you the opportunity of peering over Bohrens shoulder as he explores the world. He will take you from tavern to countryside and from a greenhouse to a murder scene, all the while teasing you into recognizing the curious clues along the way.

The experience will be rewarding and lasting. From now on, every time you see a rainbow, notice the darkening of wet sand, discover your bathroom mirror covered with drops, or note the coloring of the sky during sunset, you will recall this book. Once exposed to Bohrens investigative skills, you will be unable to take the world for granted. The steam rising from a bowl of hot soup, the freezing of a country pond, and the bobbing of a toy duck will return you to Bohrens teachings. And every time you overhear someone rattling off, Well, that happens only once in a blue moon, you will remember how the moon might indeed turn blue.

Bohren has a second purpose here. He greatly enjoys tilting with the legends and blatant falsehoods that have crept into our casual descriptions of the physical world. Does warm air really hold more water vapor than cool air? Does a greenhouse actually grow warm because it traps infrared radiation? Does frost fail to develop on the grass beneath a tree because the tree shields the grass? Does sunlight actually heat the air around us? These and other questions have been answered wrongly countless times. Bohren sets us straight on the answers, taking care that we understand the principles sufficiently so that we never repeat the mistakes.

The content of the book runs the spectrum from serious to playful. However, throughout, it rings with a unifying tone: the science of the everyday physical world is fun. And so is this book.

Jearl Walker

Physics Department,

Cleveland State University

author of The Flying Circus of Physics

and The Amateur Scientist, monthly in Scientific American

Preface

It is strange that I find myself writing this book. When I was younger I fancied myself as a theoretical physicist, that is, a manipulator of cabalistic symbols. Toward the middle of 1978, however, I found myself in somewhat of a bind. I was about to end three years as an expatriate in Wales and return to the United States, where my prospects seemed bleak.

But on a brief visit to the University of Arizona I happened to run into Louis Battan, the late director of the Institute of Atmospheric Physics. When in the course of our conversation he learned that one of the purposes of my visit was to find work, he asked me if I would like to teach elementary meteorology in the fall. I said that I didnt know anything about meteorology. Thats all right, he responded without flinching, neither do the students. And so it was that in September I found myself hearing for the first time about meteorologyfrom my own mouth.

My students were nonscience majors, although anti-science would perhaps be closer to the mark. It didnt take me long to realize that I could not reach them by the kinds of arguments and approaches that appealed to me. The merest whiff of an equation would stampede them to the deans office to complain about cruel and unusual punishment. Carefully crafted syllogisms moved them about as much as it would have moved a team of sled dogs. What did move them, I discovered, were things they could see and hear and touch. So I began trying to devise simple demonstrations to help convey physical ideas. I made a point of always bringing some objecta glass of water, an iron barto class with which to punctuate my lectures. The success of each demonstration stimulated me to devise more.

Next page