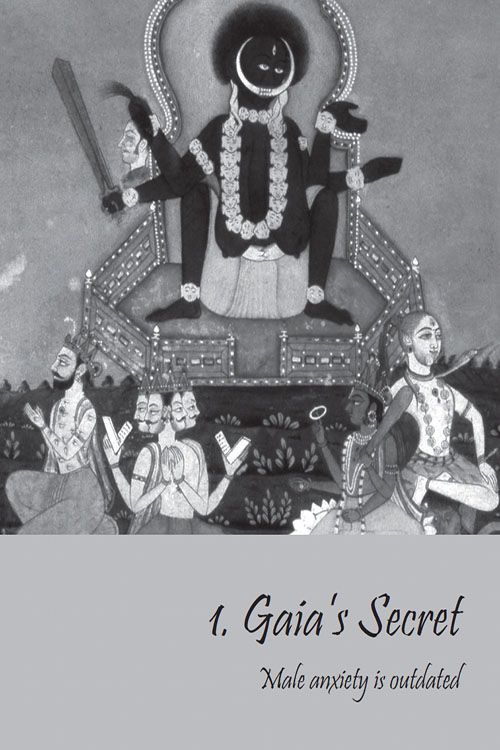

Secrets of the

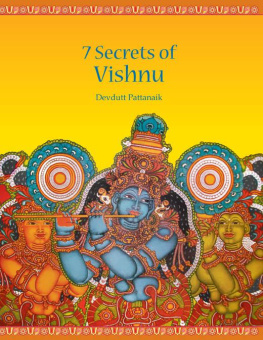

goddess Devdutt Pattanaik is a medical doctor by education , a leadership consultant by profession, and a mythologist by passion. He writes and lectures extensively on the relevance of stories, symbols and rituals in modern life. He has written over twenty-five books which include 7 Secrets of Hindu Calendar Art (Westland), 7 Secrets of Shiva (Westland) and 7 Secrets of Vishnu (Westland). To know more visit devdutt.com 7 Secrets of the

Goddess Devdutt Pattanaik

westland ltd 61 Silverline, 2nd Floor, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095 No. 38/10 (New No.5), Raghava Nagar, New Timber Yard Layout, Bengaluru 560 026 93, 1st floor, Sham Lal Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110002 First published by westland ltd 2014 Copyright Devdutt Pattanaik 2014 All rights reserved First ebook edition: 2014 ISBN: 978-93-84030-58-2 Typeset and designed by Special Effects, Mumbai This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, circulated, and no reproduction in any form, in whole or in part (except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews) may be made without written permission of the publishers. I humbly and most respectfully dedicate this book to those

hundreds of artists, artisans and photographers who

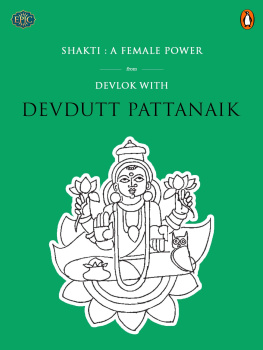

made sacred art so easily accessible to the common man Contents Authors Note On Reality and Representation L akshm i mas sages Vishnus feet. Is this male domination? Kali stands on Shivas chest. Is this female domination? Shiva is half a woman. Is this gender equality? Why then is Shakti never half a man? Taken literally, stories, symbols and rituals of Hindu mythology have much to say about gender relationships. Taken symbolically, they reveal many more things about humanity and nature. Which is the correct reading? Who knows? Within infinite myths lies an eternal truth Who knows it all? Varuna has but a thousand eyes Indra, a hundred You and I, only two. On Capitalisation C apitalisation is found in the English script but not in Indic scripts. So we need to clarify the difference between shakti and Shakti, maya and Maya, devi and Devi, goddess and Goddess. We may not always be successful. Shakti is a proper noun, the name of the Goddess. It is also a common noun, shakti, meaning power. Likewise, maya means delusion, and Maya is another name of the Goddess. The word devi, spelt without capitalisation, refers to any goddess, while Devi, spelt with capitalisation, refers to the supreme Goddess. Often Mahadevi is used for the proper noun instead of Devi. Shiva may be Mahadeva, who is maha-deva, greater than all devas; similarly Shakti is Mahadevi, who is maha-devi, greater than all devis. Without capitalisation, devi/goddess may also refer to limited forms of the female divine, while limitless ideas are referred to as Goddess/Devi using capitalisation. Ganga is devi, goddess of a river, while Gauri is Devi, Goddess embodying domesticated nature. Context needs always to be considered. Kali is goddess in early Puranas, where she is one of the divine feminine collective; later she is Goddess embodying untamed nature. Saraswati seen alone is Goddess, but when visualised next to Durga, who is Devi, she becomes the daughter, hence goddess.

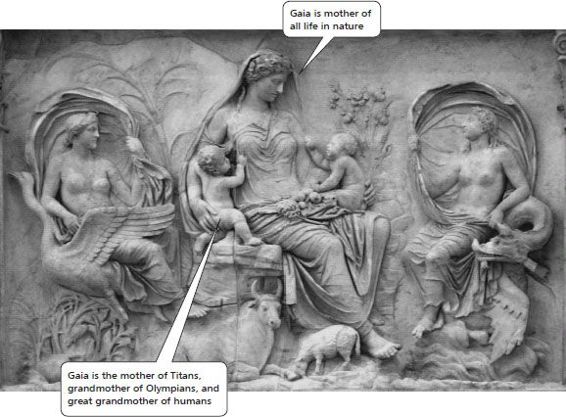

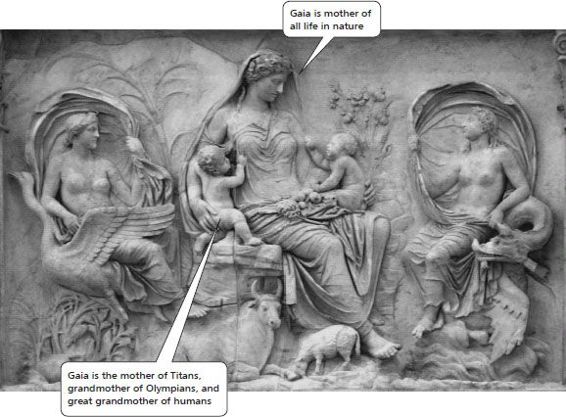

Greek mythology: Gaia, the earth-mother G aia is the earth-mother in Greek mythology. Her mate Uranus, the starry-sky, clung to her intimately and gave her no space. The only way her son, Cronus, could leave Gaias womb was by castrating his father. From the blood drops arose Aphrodite, goddess of love, and the Erinyes, the goddesses of retribution, who were fiercely protective of the mother. Cronus then declared himself king, and, to the horror of the Gaia, ate his own children to prevent them from overpowering him as he overpowered his father. Gaia saves one son, Zeus, from the brutality of Cronus, raises him in secret, and eventually Zeus attacks and kills Cronus. In triumph, Zeus declares himself father of gods of men, takes residence atop Mount Olympus that reaches into the sky. Gaia remains the earth-mother, respected but distant. This idea of a primal female deity, first adored, then brutally side-lined by a male deity is a consistent theme in mythologies around the world. The Inuit (eskimo) tribes of the Arctic region tell the story of one Sedna, who unhappy with her marriage to a seagull, begs her father to take her back home in his boat. But, as they make their way, they are attacked by a flock of seagulls. To save himself, Sednas father casts her overboard. When she tries to climb back, he cuts off her fingers. As she struggles to get back in with her mutilated hands, he cuts her arms too. So she sinks to the bottom of the ocean, her dismembered limbs transforming into fish, seals, whales, and all of the other sea mammals. Those who wish to hunt her children for food need to appease her through shamans who speak soothing words.

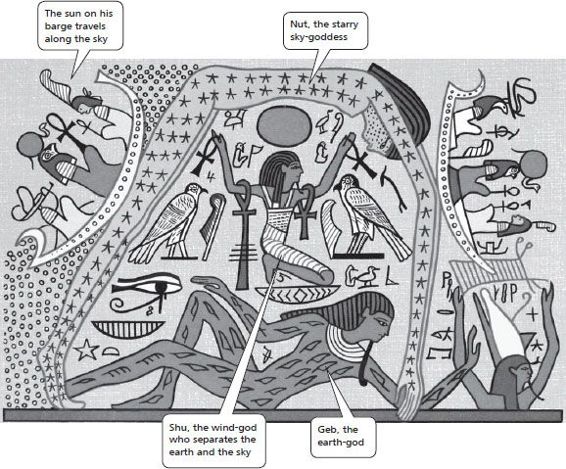

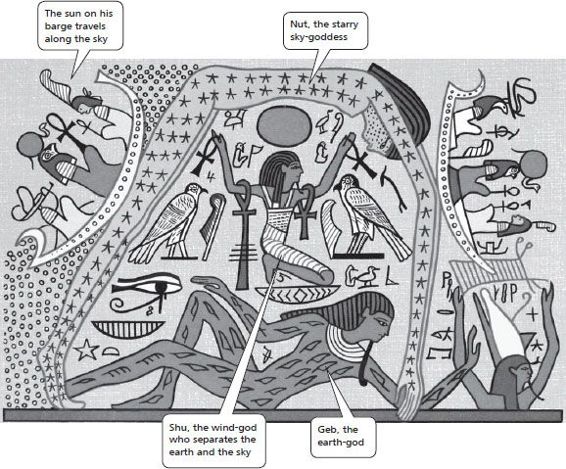

Egyptian mythology: Nut, the sky-mother The Tantrik tradition of India speaks of the primal one, Adya, who took the form of a bird and laid three unfertilised eggs from which were born Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. Adya then sought to unite with the three male gods. Brahma refused as he saw Adya as his mother; Adya cursed him that there will be no temples in his honour. Adya found Vishnu too shifty and shrewd, so she turned to the rather stern Shiva who, advised by Vishnu, agreed to be her lover provided she gave him her third eye. She did, and he used it to release a missile of fire that set her aflame and turned her into ash. From the ash came three goddesses, Saraswati, Lakshmi and Gauri who became wives of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. Also from the ash came the grama-devis, goddesses of every human settlement. Egyptian mythology acknowledges a time before gender. Then there was Atum, the Great He-She, who brought forth the god of air Shu and the goddess of dew Tefnut who separated Geb, the earth-god, from Nut, the sky-goddess, who gave birth to Isis and Osiris, the first queen and king of human civilisation. Then Seth killed Osiris and declared himself king, until Isis gave birth to Horus and contested his claim. In these stories from around the world, the male deities compete for the female prize. This can be traced to nature, where all wombs are precious but not all sperms. So the males have to compete for the female. In many bird species, the female chooses the male with the most colourful feathers, the best voice or the best song, or with the capability of building the best nest. In many animal species, such as the walrus and the lion, the alpha male keeps all the females for himself; thus there are always remainder males who do not get the female. This selection of only the best males creates anxiety amongst the not-so-good males and translates into the fear of invalidation in the human species. To cope with this fear of invalidation, social structures such as marriage laws and inheritance rights come into being, often at the cost of the female. |