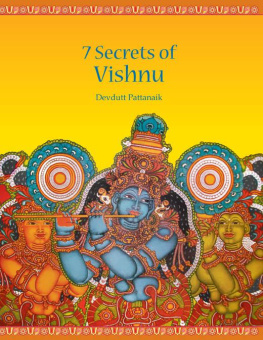

7 S ECRETS OF

S HIVA

Devdutt Pattanaik is a medical doctor by education, a leadership consultant by profession, and a mythologist by passion. He writes and lectures extensively on the relevance of stories, symbols and rituals in modern life. He has written over fifteen books which include 7 Secrets of Hindu Calendar Art (Westland), Myth=Mithya: A Handbook of Hindu Mythology (Penguin), Book of Ram (Penguin), Jaya: An Illustrated Retelling of the Mahabharata (Penguin).

To know more visit devdutt.com

westland ltd

Venkat Towers, 165, P.H. Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600 095

No. 38/10 (New No.5), Raghava Nagar, New Timber Yard Layout, Bangalore 560 026

Survey No. A - 9, II Floor, Moula Ali Industrial Area, Moula Ali, Hyderabad 500 040

23/181, Anand Nagar, Nehru Road, Santacruz East, Mumbai 400 055

4322/3, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002

First published by westland ltd 2011

Copyright Devdutt Pattanaik 2011

All Rights Reserved

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN: 978-93-80658-63-6

Typeset and designed by Special Effects, Mumbai

Printed at Thomson Press (India) Ltd.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, circulated, and no reproduction in any form, in whole or in part (except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews) may be made without written permission of the publishers.

I humbly and most respectfully dedicate this book to

those hundreds of artists and artisans who made

sacred art so easily accessible to the common man

Contents

Authors Note

On Context and Structure

I magine a Western scholar. He, or she, is typically from Europe or America. All his life, he has been exposed to Judaism, Christianity or Islam, religions that frown upon any overt display of sexuality. To him, sexuality is almost always an act of rebellion, an expression of defiance against the establishment. It is seen as being modern.

So imagine his surprise when he comes to India and encounters temples embellished with images of men and women in erotic embrace. Imagine his bewilderment when he finds Hindus worshipping an image shaped like a phallus called Shiva-linga. This is what his ancestors, a hundred years ago, also encountered, and condemned as pre-modern, licentious and savage. The scholar finds them vicariously liberating. Keen to study and understand these images, he hunts for a suitable academy. He finds none in India. So he enrols in a Western institution, where he is guided by Western academicians and is expected to follow methodologies developed and approved in the West. He starts reading texts as he would read the Bible, not realising that texts do not serve the same purpose in Hinduism. He decodes scriptures and images using his own cultural frameworks as the template. His conclusions are published in respected academic papers that win him accolades from Western academia, but they discomfort, even horrify, the average Hindu devotee.

Most Hindus become defensive and, like their 19th-century ancestors, go out of their way to strip Hinduism of its sexual heritage. A few, especially those with political leanings, react violently, outraged by the conclusions. Accused of cultural insensitivity, Western scholars strike back saying that Hindus do not know their own heritage and are still viewing Hinduism through the archaic Victorian lens. Battle lines are drawn. They are still drawn. Who is right, the arrogant academician or the stubborn devotee? It is in this context that I write this book.

I have noticed that the divide between Western academicians and Hindu devotees exists in their relative attention to form and thought. Form is tangible and objective, thought is intangible and subjective. Western scholars have been spellbound by the sexual form but pay scant regard to the metaphysical thought. In other words, they prefer the literal to the symbolic. Hindu devotees, in contrast, are so focused on the metaphysical thought that they ignore, or simply deny, the sexual form. The Western preference for form over thought stems from their cultural preference for the objective over the subjective. Hindus, on the other hand, are very comfortable with the subjective, hence can easily overlook form and focus on thought. This book seeks to bridge this wide gap between academics and practice.

- The first chapter looks at the meaning of the Shiva-linga beyond the conventional titillation offered by a phallic symbol

- The second chapter focuses on Shivas violent disdain for territorial behaviour amongst humans

- The third and fourth chapters deal with how the Goddess gets Shiva to engage with the world out of compassion

- The next two chapters revolve around Shivas two sons, Ganesha and Murugan, through whom he connects with the world

- The final chapter presents Shiva as the wise teacher who expresses wisdom through dance

This book seeks to make explicit patterns that are implicit in stories, symbols and rituals of Shiva firm in the belief that:

Within Infinite Truths lies the Eternal Truth

Who sees it all?

Varuna has but a thousand eyes

Indra, a hundred

And I, only two

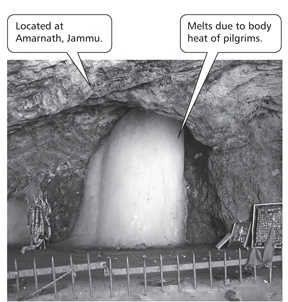

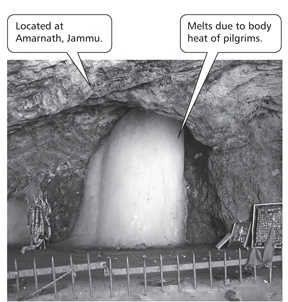

Icicle Shiva-linga

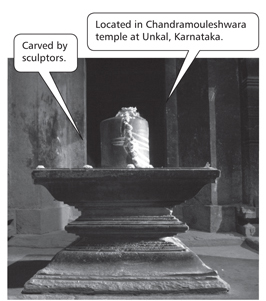

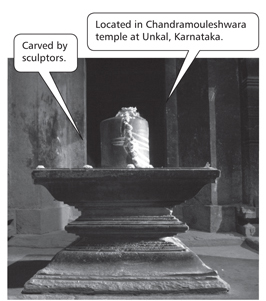

Carved Shiva-linga

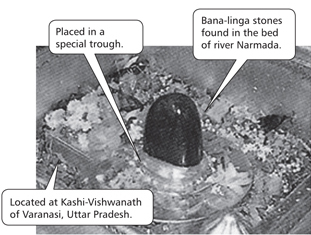

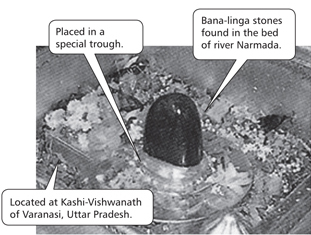

River stone Shiva-linga

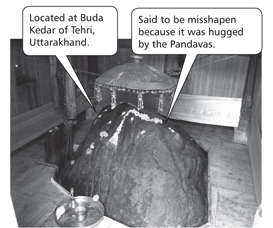

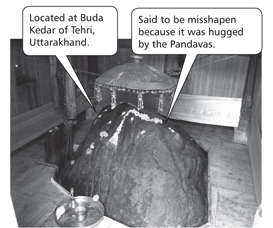

Natural rock formation Shiva-linga

O ne day a sculptor was given a rock and asked to carve an image of God. He tried to imagine a form that would best encapsulate God. If he carved a plant, he would exclude animals and humans. If he carved an animal, he would exclude humans and plants. If he carved a human, he would exclude plants and animals. If he carved a male, he would exclude the female. If he carved a female, he would exclude all males. God, he believed, was the container of all forms. And the only way to create this container was by creating no form. Or maybe God is beyond all forms, but a form is needed to access even this idea. Overwhelmed by these thoughts, the sculptor left the stone as it was and bowed before it. This was the linga, the container of infinity, the form of the formless, the tangible that provokes insight into the intangible.

The name given to God was Shiva, which means the pure one, purified of all forms. Shiva means that which is transcendent. Shiva means God who cannot be contained by space or time, God who needs no form.

Shiva has been visualised as an icicle in a cave in Amarnath, Jammu; as a natural rock formation rising up from the earth, as in Buda Kedar at Tehri, Uttarakhand or Lingaraja, Bhubaneswar, Orissa; as a smooth oval stone from the river bed of Narmada placed in a metal trough as in Kashi-Vishwanath, Varanasi; or a sculpture of a smooth cylindrical free standing pillar rising up from a leaf-shaped base as in Brihadeshwara, Tanjore or the Chandramouleshwara temple at Unkal, Karnataka.

Next page