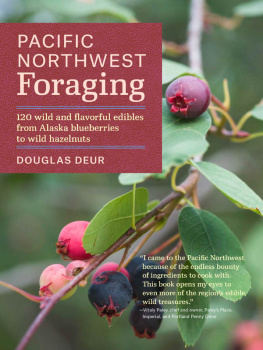

PACIFIC NORTHWEST

Foraging

120 wild and flavorful edibles from Alaska blueberries to wild hazelnuts

DOUGLAS DEUR

TIMBER PRESS

Portland.London

Frontispiece: Wildflower fields of biscuitroot yellow and camas blue sprawl across undisturbed lands in the interior Northwest, their sweet and flavorful roots lying just below the ground.

The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without guarantee on the part of the author or Timber Press. The author and publisher disclaim any liability in connection with the use of this information. In particular, eating wild plants is inherently risky. Plants can be easily mistaken and individuals vary in their physiological reactions to plants that are touched or consumed.

Photography credits appear on page 278.

Copyright 2014 by Douglas Deur.

All rights reserved.

Published in 2014 by Timber Press, Inc.

The Haseltine Building

133 S.W. Second Avenue, Suite 450

Portland, Oregon 97204-3527

timberpress.com

6a Lonsdale Road

London NW6 6RD

timberpress.co.uk

Text and cover design by Benjamin Shaykin

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Deur, Douglas, 1969

Pacific Northwest foraging: 120 wild and flavorful edibles from Alaska blueberries to wild hazelnuts/Douglas Deur.1st ed.

p. cm.

120 wild and flavorful edibles from Alaska blueberries to wild hazelnuts

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-60469-615-8

1. Wild plants, EdibleHarvestingNorthwest, Pacific. I. Title. II. Title: 120 wild and flavorful edibles from Alaska blueberries to wild hazelnuts.

QK98.5.U6D485 2014

581.63209795dc23

2013040722

To my teachers and their teachers before them.

Contents

Preface

Growing up between Portlands exurban fringe and Oregons wind-beaten north coast, I experienced a childhood that played out alongside the deep green backdrop of Northwestern native plants. My earliest memories involve crawling through patches of wild strawberries that my mother had transplanted and tended into a robust backyard groundcover. When, as a toddler, I needed to nap but resisted, my mother walked me through the Douglas-fir and cedar forest behind our home, asking me to identify each plant by name until fatigue set in and I drifted off to sleep, with visions of Oregon grape and wild lilies dancing in my head. We cut trails into the blackberry thicket tangles in summertime to find the biggest and juiciest berries. We scaled mountains, where we gathered wild onions and ate handfuls of huckleberries as we watched ravens and red-tailed hawks ride the thermals below. Academic confirmation of these landscape lessons came from unique venues: special wild food programs sponsored by the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry and other regional organizations, taught by retired professors and earnest hippy biologists. Cumulatively, these experiences were the cornerstones of my early education and gave me insights that I still draw from as a professor and researcher today. I sincerely hope that future generations of children will be so fortunate as to experience this kind of hands-on learning upon the land and, through that process, gain a profound love and understanding of this verdant home of ours. If this book helps a parent usher even one child along a similar journey, I will consider the entire writing project a great success.

As I entered adulthood, though, I was disappointed to learn that the landscapes and plants that I valued so much were seen as an anonymous tangle to many Northwesterners, just so much green noise scarcely noticed as they motored past or bulldozed through. I increasingly sensed the nagging truth behind Lewis Mumfords admonition that our national flower had become the concrete cloverleaf of the highway interchange, even here in the Pacific Northwest. Perhaps it is the fact that we Americans mostly descend from immigrant peoples, with relatively shallow histories in this far-flung corner of the continent. Perhaps it is the fact that we are largely children of an urbanized, industrial age, which has undervalued those resources that are local, wild, and free in exchange for those that are universal, interchangeable, and revenue-producing. Whatever the reason, I have long felt that there was a need to address our chronic dissociation from the landscape. A deeper appreciation of useful plants might help us to see that landscape anew and with greater interest and investment. Certainly, edible plants are all around us, a rich source of food, beauty, entertainment, enlightenment, and many other pleasures, if only we pay attention. Ironically, we are all inheritors of a great prosperity of which most of us know very little.

Eating red huckleberries along a forest path.

Well-intentioned people have sometimes called out in alarm when they have seen my children eat even the most common edible berries, astonished, grasping for their cell phones, unsure if they should first call a poison control center or child protective services. I appreciate their concern. Fortunately, the times are changing, and people are tentatively reconnecting to plants and places in myriad ways, with welcome energy and experimentation. Workshops, field trips, blogs, and any number of other venues are emerging, celebrating native foods as a solution to many of the economic, nutritional, and ecological challenges of the age. Perhaps, in time, those well-intentioned people with the cell phones and the angst will put down their phones, pick up a berry bucket, and harvest merrily alongside my kids. We will all be better for it.

Chief Kwaxistalla Adam Dick, a highly trained Kwakwakawakw clan chief, sharing his knowledge of plant gathering traditions.

In my quest to understand these matters, I had the opportunity to work with some of the best teachers available, both in the world of academia and among the Northwests Native American cultural leaders. I worked with outstanding biogeographers and ethnobotanists in universities in Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and beyond, seeking an understanding of the natural history of the Northwest and the consequences of human activities on regional ecologies. I was also able to work with many great Native teachersKwakwakawakw (Kwakiutl), Tlingit, Coast Salish, Klamath, and many othersseeking to comprehend and help document their exceedingly rich repertoire of cultural knowledge related to plants. In time, I was adopted by more than one tribe, but most relevant here by the Kawakadillika clan of the Kwakwakawakw. Their chief, Kwaxistalla Adam Dick, has instructed me over the years with a mixture of chiefly generosity and paternal patience. Sequestered from the non-Native world as a child, Adam received from the elders of his day unique and focused training in all aspects of traditional resource management, from the mechanics of plant harvesting to the philosophical foundations of plant cultivation and associated rituals. These elders gave him this training, motivated by prophecies that through such an urgent educational undertaking they might ensure that their cultural knowledge survived into the modern day. I consider myself an enormously fortunate beneficiary of their efforts. So, too, readers of this book are beneficiaries, indirectly, of the labors of these elders hailing from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In this book, I have had to strike a balance, presenting what is common knowledge among traditional harvesters, while steering clear of the medicines, ceremonial uses, and other highly sensitive and proprietary forms of knowledge. There are no state secrets contained herein, but the content and perspectives of this book clearly bear the imprint of my own teachings from this rich and venerable tradition.

Next page