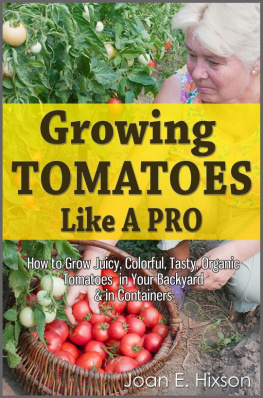

TOMATOES

A Gardeners Guide

Simon Hart

First published in 2010 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2013

Simon Hart 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 732 8

Photographic Acknowledgements

All photographs by the author, except where otherwise credited: frontispiece and pages 6, 13, 42, 106 and 121 Rhoda Nottridge; pages 11 and 16 Tony Bundock; page 25 Sue Bunwell and Andrew Davis; pages 26, 114, 115 and 116 Delfland Nurseries. Photographs on pages 7, 8, 10, 21, 22, 3739, 44, 56, 57, 62, 64, 76, 85, 88, 107 and 117119 were taken in the greenhouses of Writtle College, Essex.

Illustrations by Caroline Pratt

Nutritious and delicious, the tomato is a favourite crop for the gardener.

1 TOMATO HISTORY

The original wild tomatoes come from South America, and can still be found in Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile and Colombia. Rather oddly there is no word for the plant in early South American Indian languages, and certainly no record of its cultivation, so it seems unlikely that any of the early local inhabitants found a use for it. Of the thirteen wild species considered as tomatoes, no single one of these is recognized as being the direct ancestor of the modern cultivated tomato, though genetically the closest relative is the tiny fruited Lycopersicon pimpinellifolium, or redcurrant tomato.

The first cultivation of the tomato appears to have been by the Aztecs in what is now Mexico, some 2,000 miles distant from its native region. When the Spanish conquistadors arrived they found an advanced agricultural system, and yellow-fruited tomatoes being grown. How the Aztecs got their hands on the original plants from 2,000 miles away is something of a mystery, though a believable theory is that over time, seeds of the plants would have had found their way into the area courtesy of migrating birds. Tomato seeds are well known for their ability to pass through the digestive tract, as the stories of bumper crops of tomato plants found at sewage treatment works will support.

The tomato made its way into Europe, and also into Spanish colonies in North America and the Caribbean, in the very early 1500s, although some attribute its introduction into Europe to Columbus as early as 1498. As the first tomatoes to appear in Europe were the yellow-fruited form, they gained the name pomo doro or golden apple, which remains the same in Italian to this day. The tomato gets a mention in several of the early herbals from the mid-1500s and 1600s. Writing in 1550, Pier Andrea Mattioli used the Italian name pomodoro but he also mentioned that there was a red form of the fruit.

Initially no one seemed particularly impressed by the fruit; though edible it was identified as a close cousin of the deadly nightshade, so became regarded as slightly suspicious, if not quite as dangerous as its relative.

The date of the introduction of the tomato to England is usually given as 1596, but was almost certainly earlier as the first description of the fruit in the English language came courtesy of John Gerard in his Herball of 1597. Gerard was also fairly unimpressed, writing: In Spaine and those hot regions they used to eate the apples prepared and boild with pepper, salt and oyle, but they yeeld very little nourishment to the bodie.

Black Russian, an interesting old heritage cultivar.

Lycopersicon penellii a wild tomato.

By the end of the sixteenth century the redfruited form had become more commonplace, and in England had picked up the common name love apple; the reason for this is lost in history, possible theories ranging from the associations with the red colour of the fruit, to a misinterpretation of the name pomodoro as pomi de moro (apple of the Moors, or Spanish) and then to the French pomme damour. Whatever the origin, a reputation for aphrodisiac qualities stuck by association, and consequently the English were a bit nervous about eating the fruit, growing the plant principally as a botanical curiosity and for its ornamental value. (Interestingly the potato once commanded high prices in parts of Europe due to its reputation as an aphrodisiac, though this is more likely to have been a cunning bit of marketing than something connected with the Solanaceae in general.)

There does not appear to be a particular point at which the tomato made the transition from ornamental to edible; it is most likely that it caught on gradually. Hannah Glasses cookbook The Art of Cookery of 1758 lists a tomato recipe.

Flowers of Lycopersicon penellii.

It took until 1822 for the first specific instructions for the cultivation of the tomato to appear, by which time they were already being produced for sale in the south of England, though their popularity was not great. In William Cobbetts The English Gardener of 1829 the whole subject of the production of tomatum is disposed of in half a page, whereas the other salad staple, the cucumber, is indulged for a full nine pages. Cobbett appears fairly disinterested in the tomato, writing: The fruit is used for various purposes, and sold at a pretty high price.

AGREEING ON A NAME

In the novel Lark Rise to Candleford (set in the late 1800s) Flora Thompson describes the first appearance of red and yellow tomatoes on the local peddlers cart, saying that they had Not long been introduced into the country, and were slowly making their way into favour. Struck by the colours, the girl Laura asks what they are, and is told: Love apples, me dear, love apples, they be; though some hignorant folk be calling them tommy-toes. The name tomato appears to have come by a rather roundabout route from the Aztec Xitomatl or Tomatl, via the seventeenth-century Spanish tomate, by way of tomata in England and America in the 1800s (Dickens uses the word tomata in The Pickwick Papers) to the tomato of today.

Latin Origins: the Edible Wolf Peach

The Latin name given to the tomato is Lycopersicon esculentum, which translates as the edible wolf peach. The origin of the name Lycopersicon is attributed to the Greek naturalist Galen (129207AD), but whatever plant Galen was describing it certainly wasnt a tomato, as they didnt appear in the Mediterranean area for another 1,400 years. How the tomato took the name

Next page