Appendix. Going Further

Life was a lot easier a few years ago when I was writing Design Patterns in Ruby. Back then there were only a handful of Ruby books available, so making suggestions about where to go next was not much of a problem. These days there are so many good books about Ruby around that its hard to know where to start. Still, some classics never go out of style. So if your command of Ruby is not what it should be, try:

Thomas, D., Fowler, C., and Hunt, A. Programming Ruby 1.9: The Pragmatic Programmers Guide. Raleigh, NC: Pragmatic Bookshelf, 2008.

Programming Ruby is a very thorough but free-flowing exploration of the Ruby programming language. If you like your information more systematic and less stream-of-consciousness, you might want to go back to the source:

Flanagan, D. and Matsumoto, Y. The Ruby Programming Language. Cambridge, MA: OReilly, 2008.

Two other excellent references are:

Cooper, P. Beginning Ruby: From Novice to Professional, Second Edition. New York, NY: Apress, 2009.

And

Black, D. The Well-Grounded Rubyist. Greenwich, CT: Manning Publications, 2009.

If you are interested in the larger issues around building software with Ruby, you might also want to have a look at my own:

Olsen, R. Design Patterns in Ruby. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley, 2008.

There are also a number of other how-to style books. Here again, there is a classic:

Foulton, H. The Ruby Way, Second Edition: Solutions and Techniques in Ruby Programming, Second Edition. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley, 2006.

And a relative newcomer:

Carlson, L. and Richardson, L. Ruby Cookbook. Cambridge, MA: OReilly, 2006.

Another excellent choice, very much in the spirit of this book is:

Brown, G. Ruby Best Practices. Cambridge, MA: OReilly, 2009.

Regular expressions are a key part of any Rubyists toolkit. Two excellent references are:

Friedl, J. E. F. Mastering Regular Expressions. Cambridge, MA: OReilly, 2006.

And

Goyvaerts, J. and Levithan, S. Regular Expressions Cookbook. Cambridge, MA: OReilly, 2009.

There are two other sources of invaluable design knowledge out there. One is the source code for the various Ruby projects. Find an open source project that interests you and dig into the code. Or dig into your Ruby implementation. A good workman knows his tools.

A good workman also learns from the past. All too often when a new technology comes alongRuby, for examplewe tend to toss out the hard-won lessons of experience along with the old code. Take the time to learn from the smart people who came before you.

You might start with Paul Grahams 1993 book, On LISP. The entire text of this book is available at www.paulgraham.com/onlisp.html. It is worth reading even if you never type a single parenthesis of LISP.

In many ways this book, especially the chapter on object equality, was inspired by:

Bloch, J. Effective Java, Second Edition. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley, 2008.

Other books of this sort that are well worth a look are:

Beck, K. Smalltalk Best Practice Patterns. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1996.

Kernighan, B. and Plauger, P. J. The Elements of Programming Style. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1974.

Brodie, L. Thinking Forth. Los Angeles, CA: Punchy Publishing, 2004.

Thinking Forth is available as a free download at http://thinking-forth.sourceforge.net.

The George Orwell quote mentioned in comes from an essay called Politics and the English Language, which is widely available on the Internet and is also included in:

Orwell, G. A Collection of Essays. San Diego, CA: Mariner Books, 1970.

Finally, there is the granddaddy of them all. Im convinced that if Strunk had been a software engineer and White a coder, my personal AI assistant would be typing the last lines of this book:

Strunk, W. and White, E. B. The Elements of Style, Fourth Edition. White Plains, NY: Longman, 1999.

Chapter 1. Write Code That Looks Like Ruby

Some years ago I did a long stint working on a huge document management system. The interesting thing about this job was that it was a joint development project: Part of the system was developed by my group here in the United States and part was built by a team of engineers in Tokyo. I started out doing straight programming, but slowly my job changedI found myself doing less and less programming and more and more translating. Whenever a JapaneseAmerican meeting collided with the language barrier my phone would ring, and I would spend the rest of the afternoon explaining to Mr. Smith just exactly what Hosokawa-San was trying to say, and vice versa. What is remarkable is that my command of Japanese is practically nil and my Japanese colleagues actually spoke English fairly well. My special ability was that I could understand the very correct, but very unidiomatic classroom English spoken by our Japanese friends as well as the slangy, no-holds-barred Americanisms of my U.S. coworkers.

You see the same kind of thing in programming languages. The parser for any given programming language will accept any valid programthats what makes it a valid programbut every programming community quickly converges on a style, an accepted set of idioms. Knowing those idioms is as much a part of learning the language as knowing what the parser will accept. After all, programming is as much about communicating with your coworkers as writing code that will run.

In this chapter well kick off our adventures in writing good Ruby with the very smallest idioms of the language. How do you format Ruby code? What are the rules that the Ruby community (not the parser) have adopted for the names of variables and methods and classes? As we tour the little things that make a Ruby program stylistically correct, we will glimpse at the thinking behind the Ruby programming style, thinking that goes to the heart of what makes Ruby such a lovely, eloquent programming language. Lets get started.

The Very Basic Basics

At its core, the Ruby style of programming is built on a couple of very simple ideas: The first is that code should be crystal cleargood code tells the reader exactly what it is trying to do. Great code shouts its intent. The second idea is related to the first: Since there is a limit to how much information you can keep in your head at any given moment, good code is not just clear, it is also concise. Its much easier to understand what a method or a class is doing if you can take it all in at a glance.

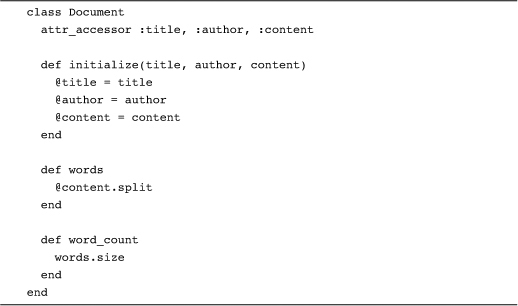

To see this in practice, take a look at this code:

The thing to note about the code above is that it follows the Ruby indentation convention: In Ruby you indent your code with two spaces per level. This means that the first level of indentation gets two spaces, followed by four, then six, and then eight. The two space rule may sound a little arbitrary, but it is actually rooted in very mundane practicality: A couple of spaces is about the smallest amount of indentation that you can easily see, so using two spaces leaves you with the maximum amount of space to the right of the indentation for important stuff like actual code.

Note that the rule is to use two spaces per indent: The Ruby convention is to never use tabs to indent. Ever. Like the two space rule, the ban on tabs also has a very prosaic motivation: The trouble with tabs is that the exchange rate between tabs and spaces is about as stable as the price of pork belly futures. Depending on who and when you ask, a tab is worth either eight spaces, four spaces, two spaces, or, in the case of one of my more eccentric former colleagues, three. Mixing tabs and spaces without any agreement on the exchange rate between the two can result in code that is less than readable:

![Russ Olsen [Russ Olsen] Eloquent Ruby](/uploads/posts/book/120775/thumbs/russ-olsen-russ-olsen-eloquent-ruby.jpg)