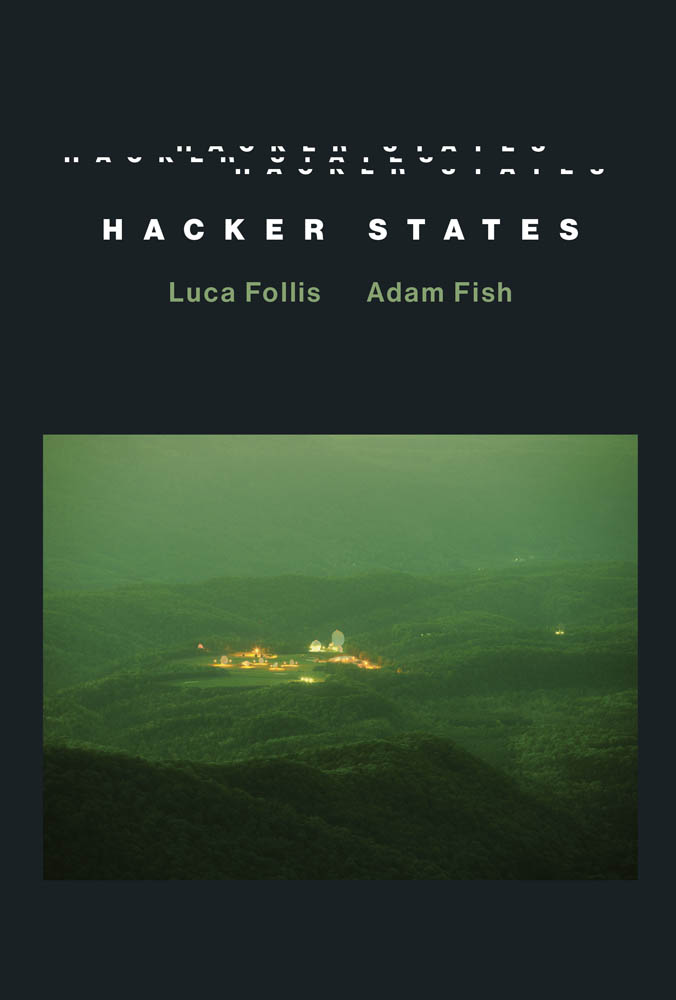

Hacker States

The Information Society Series

Laura DeNardis and Michael Zimmer, Series Editors

Interfaces on Trial 2.0, Jonathan Band and Masanobu Katoh

Opening Standards: The Global Politics of Interoperability, Laura DeNardis, editor

The Reputation Society: How Online Opinions Are Reshaping the Offline World, Hassan Masum and Mark Tovey, editors

The Digital Rights Movement: The Role of Technology in Subverting Digital Copyright, Hector Postigo

Technologies of Choice? ICTs, Development, and the Capabilities Approach, Dorothea Kleine

Pirate Politics: The New Information Policy Contests, Patrick Burkart

After Access: The Mobile Internet and Inclusion in the Developing World, Jonathan Donner

The World Made Meme: Public Conversations and Participatory Media, Ryan Milner

The End of Ownership: Personal Property in the Digital Economy, Aaron Perzanowski and Jason Schultz

Digital Countercultures and the Struggle for Community, Jessica Lingel

Cyberbullying Policies of Social Media Companies: Toward Digital Dignity, Tijana Milosevic

Authors, Users, and Pirates: Copyright Law and Subjectivity, James Meese

Weaving the Dark Web: Legitimacy on Freenet, Tor, and I2P, Robert W. Gehl

Hacker States, Luca Follis and Adam Fish

Hacker States

Luca Follis and Adam Fish

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2020 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Follis, Luca, author. | Fish, Adam, author.

Title: Hacker states / Luca Follis and Adam Fish.

Description: Cambridge, MA : MIT Press, [2020] | Series: Information society series | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019019587 | ISBN 9780262043601 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Hacktivism. | Cyberspace--Political aspects.

Classification: LCC HV6773 .F65 2020 | DDC 364.16/8--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019019587

Contents

A book begins with a collection of multiple lines of inquiry, dispersed ideas, and research trajectories that predate the research itself and seek to extend beyond it. When it is the product of collaborative work, the synthesis and clarification of ideas is perhaps more challenging but also significantly more stimulating, and I would like to thank my coauthor Adam Fish for being a thoughtful, imaginative interlocutor during the years we spent researching and writing this book. Throughout this process, I have drawn significant inspiration from the interdisciplinary spirit that animated my PhD years at the New School for Social Research in New York and the critical focus on the themes of democracy, crisis, and resistance that characterized my time there. The guidance, mentorship, and support of a theoretically agile and politically engaged group of scholarsAndrew Arato (to whom I owe a tremendous intellectual debt), Oz Frankel, Eiko Ikegami, Jeffrey Goldfarb, Elbieta Matynia, and Jos Casanovais reflected in many of the pages of this book.

In Lancaster and beyond, many colleagues generously gave their time and effort to comment on, discuss, and otherwise significantly improve various drafts of this book. In particular, I would like to thank Monika Buscher, Mark Lacy, Daniel Prince, Majid Yar, and Maxigas. Others helped provide the vibrant and collegial research environment that allowed this project to develop. Sue Penna, Corinne May-Chahal, Alisdair Gillespie, Sigrun Skogly, Catherine Easton, Sarah Kingston, Gary Potter, and Steven Wheatley deserve special thanks. Security Lancaster and the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Lancaster University provided funding at various stages of this research and the law school facilitated a timely research sabbatical during which the final draft of this manuscript was completed. I would also like to extend our gratitude to our informants, in particular Lauri Love and Naomi Colvin, who gave us access to their timeunder incredibly stressful conditionsso that we could write this book. Our editor at the MIT Press, Gita Devi Manaktala, and four anonymous readers also contributed to making our manuscript better.

Finally, I would especially like to thank my parents Eugenia and Fabrizio Follis, who regularly provide a respite from the storm of academic commitments and are an unwavering source of support and encouragement, as well as Marco Follis, Anna Maria Notaro, Jolanta Zagrodzka, and Jerzy Szmagalski, whose enthusiasm, engagement, and warmth throughout the writing of this book kept me grounded. Above all this project would not have been possible without my travel partner in life, academia, and all else. I would like to thank Karolina Follis, whose encouragement, love, and boundless imagination powers our little family, as well as the restless and incandescent spirit of our two children, Benjamin and Matilda. When they smile, the worries of the world fade away.

Luca Follis

I would like to sincerely acknowledge the creative work of my coauthor Luca Follis. His dedication to grounded realism, steady discipline, and playful theorizing made this project possible. A community of fellow anthropology hackersChristopher Kelty, Gabriella Coleman, Maxigas, and Paula Bialskiinspired this research. I appreciated the opportunity to present drafts of this research at the Digital Social Research Unit, Ume University, Sweden; Disconnections Symposium, Uppsala University, Sweden; ZeMKI Centre for Media, Communication and Information Research, University of Bremen, Germany; and Hackademia: Empirical Studies in Computing Cultures, Lneburg Summer School for Digital Cultures, Leuphana University, Germany. I thank the ZeMKI Centre for Media, Communication, and Information Research for a 2018 fellowship that supported this research. My family, Robin, Io (Isis Viola Lune Moxie), and Jennifer Fish, made this and all work meaningful. I dedicate this work to Richard Lee Fish (19472018), a hacker in spirit.

Adam Fish

The smell of pinecones roasting on black basalt rock. Icy creeks replenishing free-flowing rivers, where salmon swim to peak-side spawning grounds. On a sandy beach, prints of bighorn sheep scatter away from an ambush by a mountain lion. Situated in central Idaho, between Montana and Oregon, this is the largest roadless area in the lower forty-eight United States. It is one of the only remaining intact ecosystems large enough to support ambulatory and predatory megafauna like wolverines, gray wolves, lynx, mountain lion, and likely grizzly bears. This wilderness is protected on the grounds that it sustains biological richness, allows scientists to observe ecological principles, inspires a freedom-seeking zeitgeist, reminds people of commonly shared responsibilities, and serves as a sacred space (Nash 1976). Authors from Henry David Thoreau to Edward Abbey have noted the dialectic between internal wildness and external wilderness that exists in the American psyche, a co-determining relationship between a peoples values and what a nation cherishes. An immense wilderness in Idaho might seem an unlikely place to begin a book about computer hacking. Yet the internetand the sprawling network of servers, computers, and other devices that constitute itforms its own kind of wilderness. Fin de sicle computer viruses, self-replicating worms, and other malware swim in the fiber-optic streams of this wild. As an untamed region far removed from the sandbox of computer laboratories and research facilities, the hacker wilderness is the space where security researchers, cybercriminals, and hacktivists meet and mesh. Thinking about the relationship between the nation-state and the wild offers important insights into todays fight for the cyber commons.

Next page