For online information and ordering of these and other Manning books, please visit www.manning.com. The publisher offers discounts on these books when ordered in quantity.

Manning Publications Co.

2021 by Manning Publications Co. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in the book, and Manning Publications was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial caps or all caps.

Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, it is Mannings policy to have the books we publish printed on acid-free paper, and we exert our best efforts to that end. Recognizing also our responsibility to conserve the resources of our planet, Manning books are printed on paper that is at least 15 percent recycled and processed without the use of elemental chlorine.

front matter

foreword

Ive spent a lot of my life thinking about programming, and if youre reading this book you probably have too. I havent spent nearly as much time thinking about thinking, though. The concept of our thought processes and how we interact with code as humans has been important to me, but there has been no scientific study behind it. Let me give you three examples.

Im the main contributor to a .NET project called Noda Time, providing an alternative set of date and time types to the ones built into .NET. Its been a great environment for me to put time into API design, particularly with respect to naming. Having seen the problems caused by names that make it sound like they change an existing value, but actually return a new value, Ive tried to use names that make buggy code sound wrong when you read it. For example, the LocalDate type has a PlusDays method rather than AddDays . Im hoping that this code looks wrong to most C# developers

date.PlusDays(1);

whereas this looks more reasonable:

tomorrow = today.PlusDays(1);

Compare that with the AddDays method in the .NET DateTime type:

date.AddDays(1);

That looks like its just modifying date , and isnt a bug, even though its just as incorrect as the first example.

The second example is also from Noda Time, but its not quite as specific. Whereas many libraries try (for good reason) to do all the hard work without developers having to think much, we explicitly want the users of Noda Time to put a lot of thought into their date and time code up front. We try to force users to put thought into what theyre really trying to achieve, with no ambiguityand then we try to make it easy to express that clearly in the code.

Finally, theres the one conceptual example of what values variables hold in Java and C# and what happens when you pass an argument to a method. It feels like Ive been trying to counter the notion that objects are passed by reference in Java for most of my life, and when I do the math, thats probably the case. I suspect Ive been trying to help other developers fine-tune their mental models for about 25 years now.

It turns out that how programmers think has been important to me for a long time, but with no science behind it, just guesswork and hard-won experience. This book helps to change that, although it isnt quite the start of this process for me.

I first came across Felienne Hermans at the NDC conference in Oslo in 2017 when she gave her presentation Programming Is Writing Is Programming. My reaction on Twitter says it all: I need a long time to let it all sink in. But wow. Wow. Ive seen Felienne give this presentation (evolving over time, of course) at least three times now and have taken something new out of it each time. Finally there were some cognitive explanations for the things I had been trying to doand also some surprises that challenged me to tweak my approach.

Alternating reactions of Ah, that makes sense now! and Oh, I hadnt thought of that! have been the background rhythm when reading this book. Aside from some immediate practical suggestions such as using flashcards, I suspect the impact of the book will be more subtle. Maybe its a little more deliberation about when to put a blank line in code. Maybe its a change in the tasks we give to new members of the team, or even just a change in the timing of those tasks. Maybe its how we explain concepts on Stack Overflow.

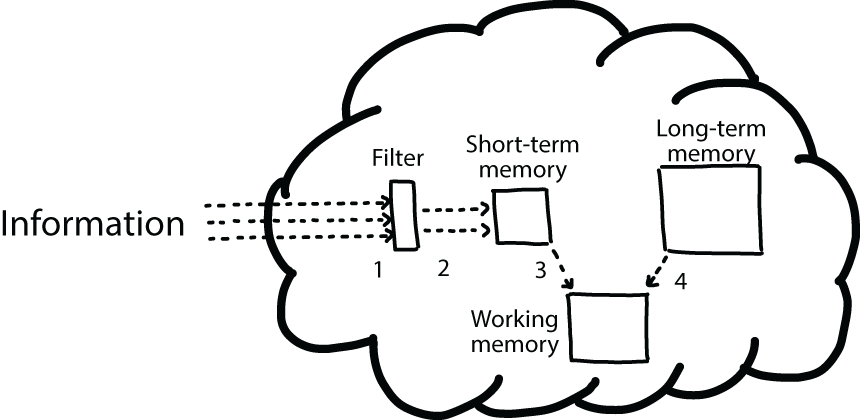

Whatever the impact, Felienne has provided a treasure chest of ideas to think about and to process in working memory and move to long-term memorythinking about thinking is addictive!

Jon Skeet

Staff Developer Relations Engineer, Google

preface

When I started to teach children to program about 10 years ago, I quickly realized I didnt have the faintest idea how people use their brains for anything, especially for programming. While I learned a lot about programming in university, no course in my computer science education had prepared me to think about thinking about programming.

If you followed a computer science program like I did, or if you learned programming by yourself, you most likely did not learn about the cognitive functions of the brain. Therefore, you might also not know how to improve your brain to read and write code in a better way. I certainly did not, but while teaching kids to program, I realized I needed a deeper understanding of cognition. I then set out to learn more about how we think and how we learn. This book is the result of the last few years of me reading books, talking to people, and attending talks and conferences about learning and thinking.