For my son, Owen

A note from the author

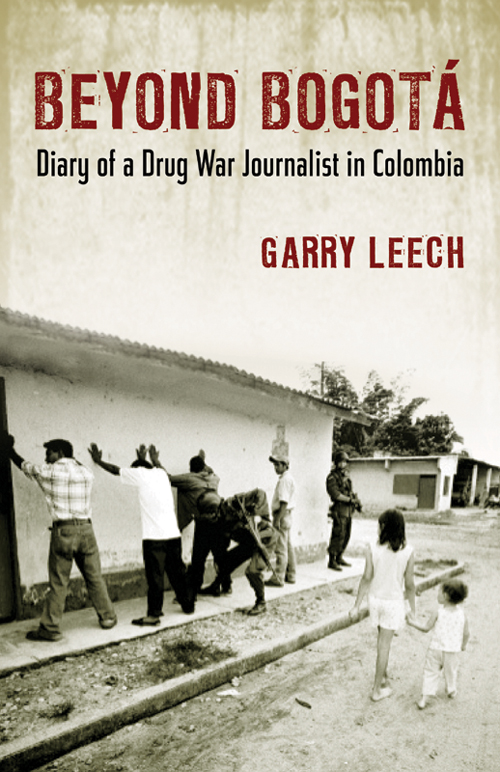

The idea for this book emerged during an eleven-hour detention I endured at the hands of Colombias largest guerrilla group in August 2006. More specifically, it evolved from thoughts that washed over me during that ordeal about my three-month-old son, Owen. I couldnt stop thinking that if anything happened to me, either during that detention or at any other time in Colombia, I wouldnt be around to explain to Owen, when he grew up, what sort of work his father did. Sure, he could read my articles and books and discover my views on U.S. policy in Colombia. But those writings do not explain how I conduct my work. They dont describe the challenges and adventures involved in carrying out investigative journalism in Colombias remote rural conflict zones. And they dont depict the moments of terror or those of inspiration that I have experienced in my encounters with Colombians from many walks of life. Most importantly, they dont shed light on why I do this sort of work and the path that led me to become a drug war journalist. Consequently, Beyond Bogot is the story of my work in Colombiaa sort of memoir, if you will.

Naturally, my story cannot be separated from the larger drama in which the principal protagonists are Colombians who are living and dying every day in the midst of the countrys decades-old civil conflict. Colombia is the worlds leading producer and exporter of cocaine, and its illegal drug trade has fed the habits of drug users in the United States for more than three decades. As a result, we Americans are directly linked to Colombias violent drama, both through ever-rising levels of personal cocaine use and through the war on drugs that our government has been waging in this South American country.

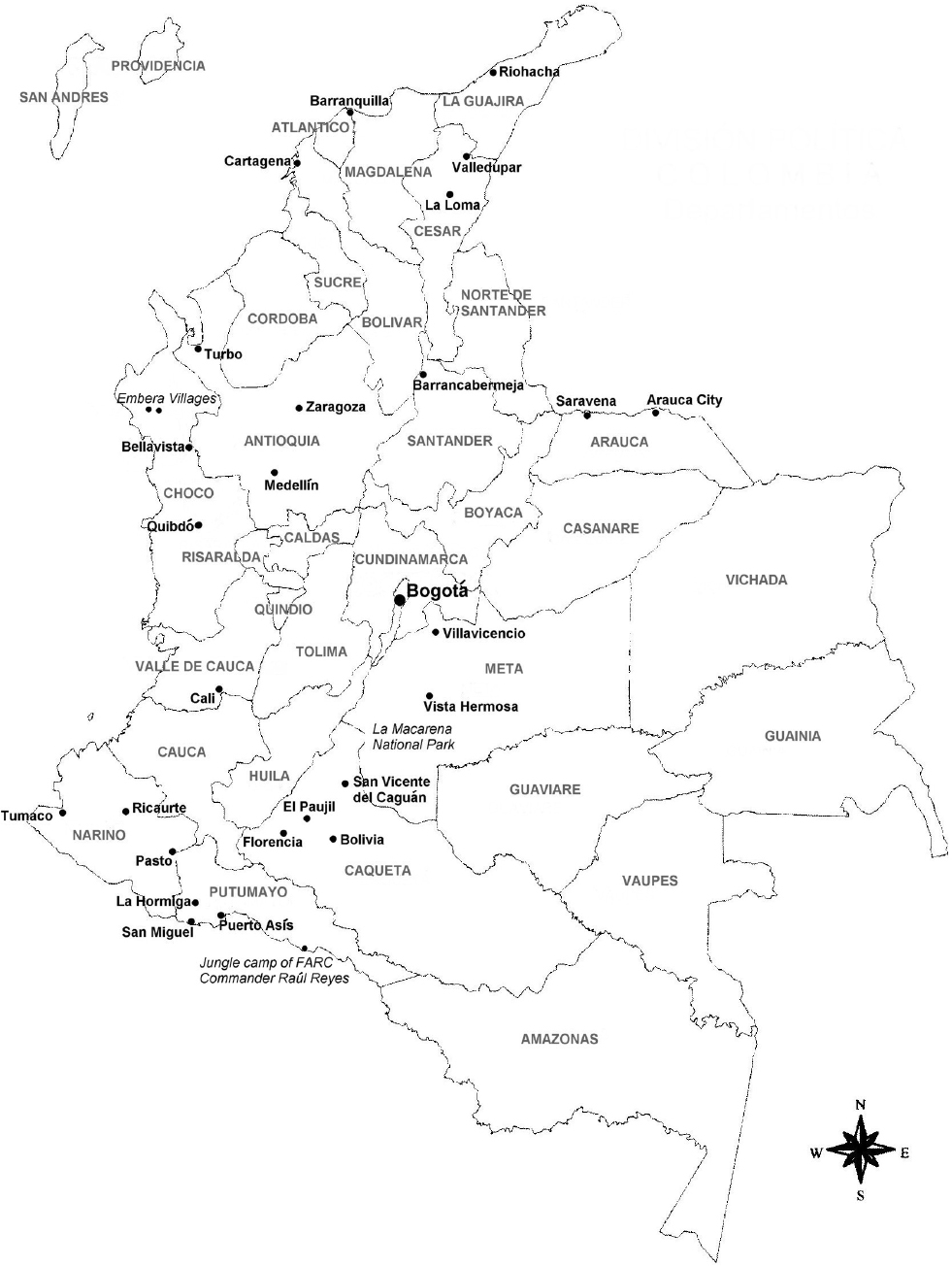

I have tried to place my personal story within the larger contexts of the U.S. war on drugs and Colombias civil conflict. I have drawn from my experiences working in various parts of Colombia over the past eight years in an attempt to portray, as comprehensively as possible, both my personal story and the struggles of those rural Colombians who are caught in the middle of the violence. There are not enough pages in this book for me to include all of the Colombians I have met or even to reflect on every region of the country in which I have worked. Therefore, I have selected those people and places that I hope will provide the reader with a relatively comprehensive portrayal of life in Colombias rural conflict zones. Woven throughout are accounts of the most profound and personal of my own experiences in Colombia. Sadly, for their own safety, I have had to change the names of some of the protagonists. I have not, however, altered the names of those Colombians who are already public figures or visible spokespersons for governments, organizations, communities, or armed groups.

Ultimately, this book is an account of the U.S. war on drugs and Colombias civil conflict as seen through the eyes of a journalist. Colombias civil conflict and the war on drugs are complex issues, and I dont for a moment pretend that I fully grasp all of their intricacies or that I have sufficiently addressed them in these pages. What I have tried to do is to recount my experiences and observations as accurately and honestly as possible. Beyond Bogot is not a journalistic work, but rather the personal story of a journalists search for meaning in the midst of violence and poverty.

The First Hour

10:00 a.m., August 16, 2006

They order me to sit in a white plastic chair. One of the guerrillas remains behind to guard me while the other two rebels depart in a maroon Toyota SUV. My guard sits across from me in a similar white plastic chair and shows no interest in engaging me in conversation. He appears to be in his late fifties, with shoddy gray hair and a weather-beaten face that suggests he has endured many years of hard living. He is wearing a frayed red dress shirt and beige pants. A revolver in a leather holster is slung low on his right hip, giving him the appearance of a gunslinger in an old cowboy movie. Propped against the wall next to him, within easy reach, is a fully locked and loaded AK-47 assault rifle.

Im sitting in a wooden shack on a remote farm. It has three rooms, each extending from the front to the rear of the small house. From my chair in the central room, which is open to the outside on both ends, I can see a middle-aged woman cooking in the outdoor kitchen behind the house and a teenage girl minding a small baby.

My guard passes the time listening to an old black plastic radio that he holds in his lap, occasionally shifting its position to ensure continued good reception. He does not engage in channel surfing; instead, the radio remains firmly set on one station. That station is called Radio Resistencia, and it is broadcast by my guards rebel group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, better known by its Spanish-language acronym, FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia). Although the FARC claims to be fighting for political, social, and economic justice in Colombia, the U.S. State Department has listed the group as an international terrorist organization since 1997.

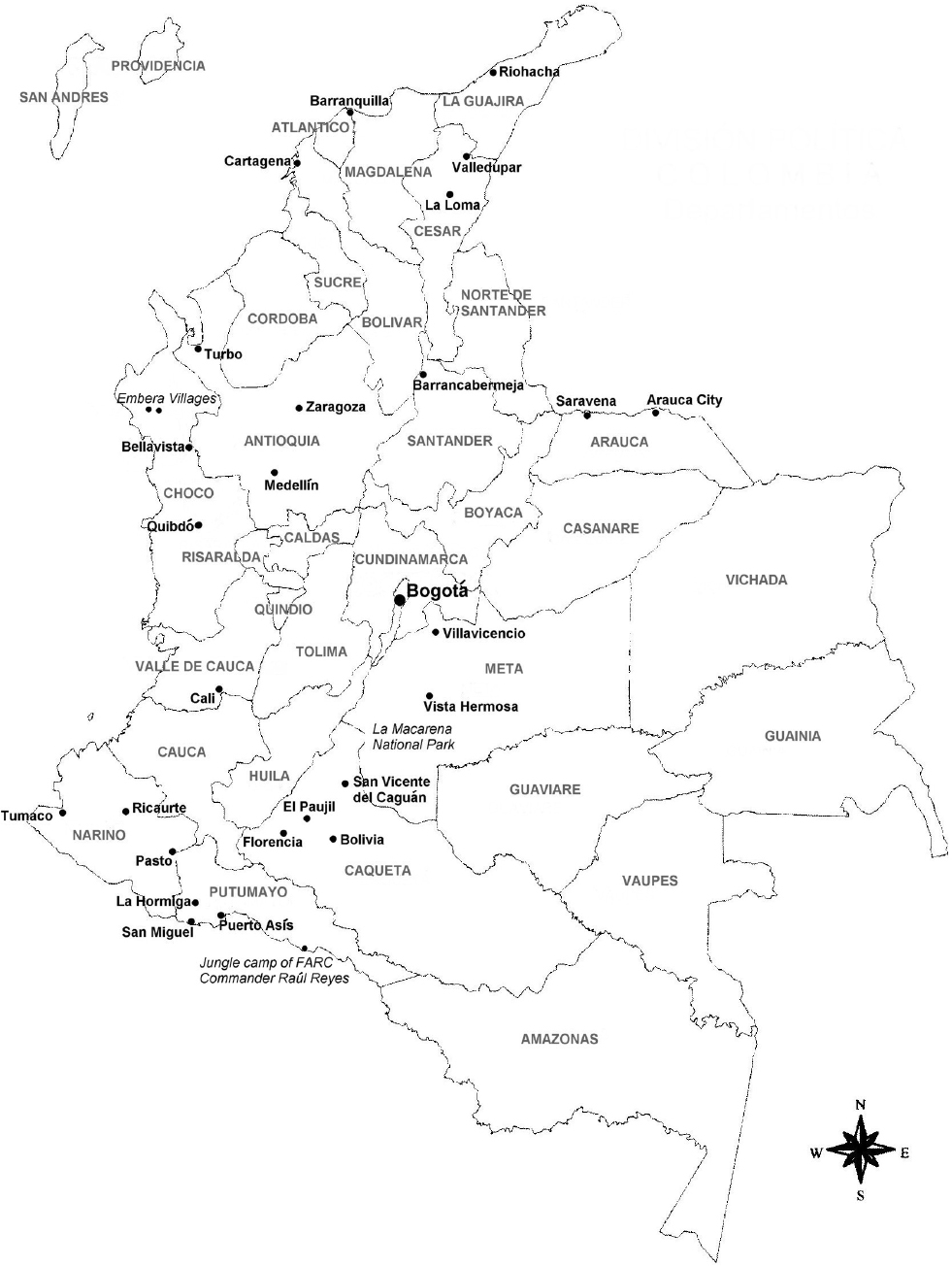

Last night I arrived in the town of Vista Hermosa in eastern Colombia. My objective was to investigate the consequences in La Macarena National Park of the recent aerial fumigations of coca, the plant whose leaves are the raw ingredient of cocaine. The story is important because the fumigations mark an escalation in the war on drugs, since it is the first time the Colombian government has succumbed to pressure from the Bush administration to spray coca crops cultivated in one of the countrys biologically diverse national parks.

Early this morning, after spending the night in a basic but clean hotel room, I hired a driver named Javier and his four-wheel-drive jeep to take me into La Macarena. On the way out of town, we stopped at the final police checkpoint in the government-controlled part of this region. When I told the officer that I was going to La Macarena to investigate the fumigations, he asked me to step out of the jeep and to follow him into the local base of the National Police. Inside the base, officials told me to sign a waiver stating that they had warned me that I was entering guerrilla country and that the National Police wouldnt be held responsible for anything that might happen to me. The waiver served two purposes for the authorities. It helped protect them if I were to be kidnapped or, worse yet, killed by the rebels. It also allowed them to track the movements of people in the region. I wasnt completely comfortable with this, but agreeing to sign the waiver was the only way through the checkpoint.

After leaving the checkpoint, Javier and I made our way across the river into FARC-controlled territory. We drove past cows grazing lazily in the fields, with the lush green hills of La Macarena half-hidden behind a thin, mystical layer of fog to our right. The road was rough, wet and muddy from recent rains, and in many places only wide enough for one vehicle. We crossed numerous streams and rivers, some via primitive wooden bridges, others by utilizing the vehicles four-wheel drive to wade through the flowing waters. We saw few dwellings along our route into the park, save for a couple of tiny villages consisting of a handful of simple wooden houses.