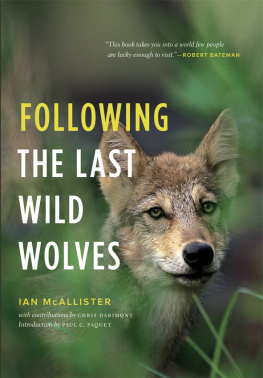

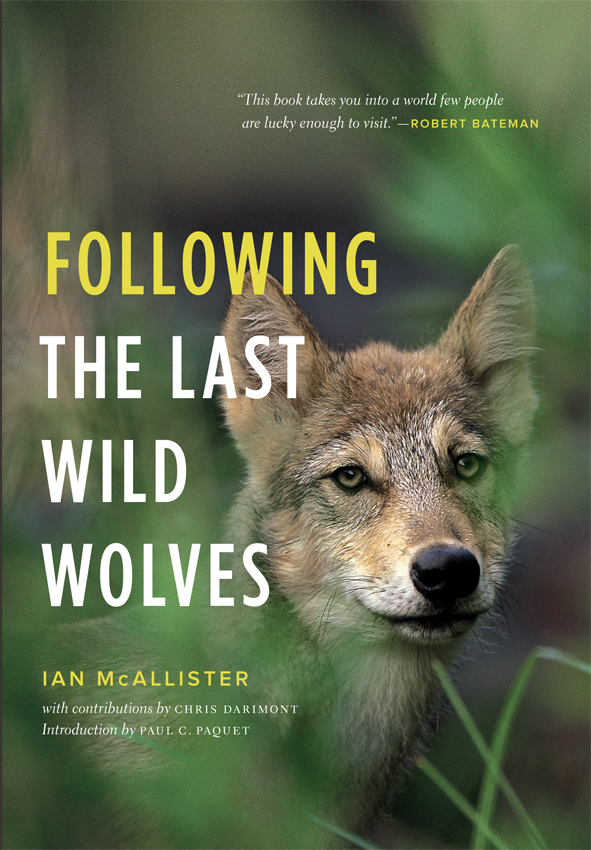

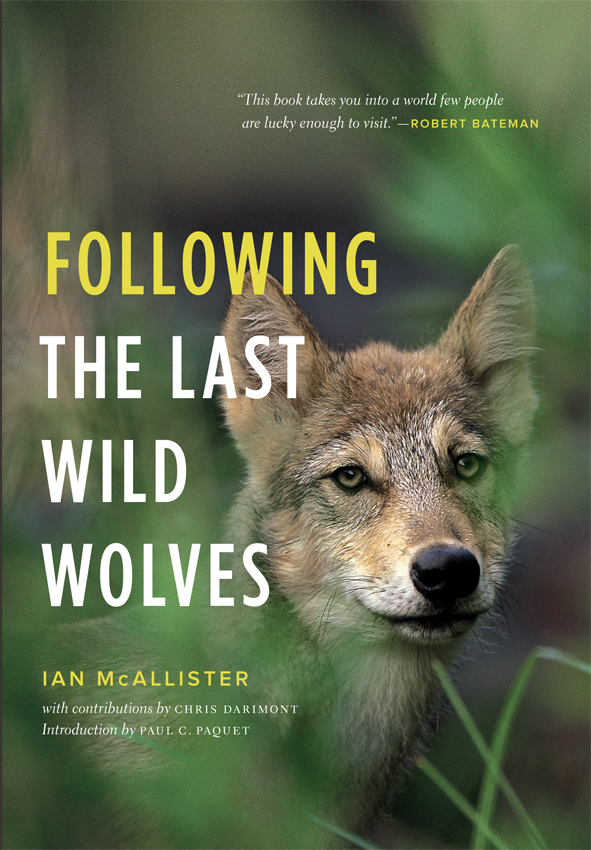

FOLLOWING

THE LAST

WILD

WOLVES

FOLLOWING

THE LAST

WILD WOLVES

IAN McALLISTER

with contributions by Chris Darimont

Introduction by Paul C. Paquet

Text and photographs copyright 2007 and 2011 by Ian McAllister

Introduction copyright 2007 and 2011 by Paul C. Paquet

11 12 13 14 15 5 4 3 2 1

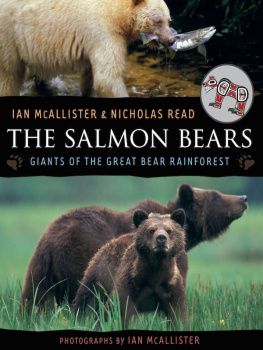

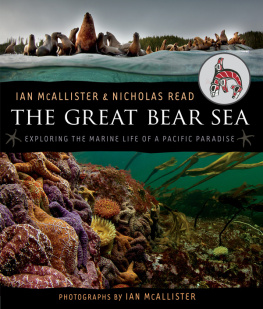

The images and an earlier version of the text in Following the Last Wild Wolves originally appeared in The Last Wild Wolves, published in 2007 by Greystone Books.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Greystone Books

An imprint of D&M Publishers Inc.

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver BC Canada V5T 4S7

www.greystonebooks.com

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-55365-587-9 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-1-55365-420-9 (ebook)

Editing by Nancy Flight

Copy editing by Wendy Fitzgibbons

Cover design by Jessica Sullivan and Naomi MacDougall

Cover photograph by Ian McAllister

Interior photos by Ian McAllister

Distributed in the U.S. by Publishers Group West

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

For Karen, Callum, and Lucy,

who make for the best of all journeys.

CONTENTS

PAUL C. PAQUET, PHD

I N THE past, the elusive gray wolf roamed most of the Northern Hemisphere, including nearly all of Eurasia and North America. Except for humans and possibly the African lion, gray wolves once had the most extensive range of any terrestrial mammal. They were found in a variety of environments, from dense forest to open grassland and from the Arctic tundra to extreme desert, avoiding only swamps and tropical rain forests. Now wolves occur mostly in remote and undeveloped areas of the world with sparse human populations. These few remaining secluded areas of relatively unmodified landscapes are biological and cultural treasures, our last opportunities to preserve the highly specialized and co-evolved relationships that are being replaced elsewhere with invasive species and managed landscapes.

On the North American mainland, gray wolves were once found everywhere except the southeastern United States, California west of the Sierra Nevada range, and the tropical and subtropical regions of Mexico. The species also occurred on large continental islands, such as Newfoundland and Vancouver Island, on smaller islands off coastal British Columbia and southeast Alaska, and throughout the Arctic Archipelago and Greenland but was absent from Prince Edward Island, Anticosti, and Haida Gwaii (the Queen Charlotte Islands).

Over the past four centuries, gray wolf populations in North America have been decimated by overwhelming increases in the human population, development of agriculture, and expansion of industrial forestry. Moreover, hundreds of thousands of wolves have been trapped, poisoned, shot from helicopters, and sterilized, among other modes of destruction. By the beginning of the twentieth century, wolves had nearly vanished from the eastern United States, most of southern Canada, and the Canadian Maritime provinces. By 1960, the wolf had been exterminated by federal and state governments from all of the United States except Alaska and northern Minnesota. The distribution of the gray wolf in North America is now confined primarily to Alaska and Canada. In the conterminous United States, populations in northern Minnesota, northern Wisconsin, and Michigans Upper Peninsula, as well as parts of Arizona, Washington, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, have been augmented by wolves introduced from Canada and by natural recolonization.

In Canada the gray wolf is still found throughout much of its historical range, including coastal islands. Cessation of most wolf control programs has allowed the wolf to recover in many areas where it had been extirpated, although the species is completely gone from Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick and is absent or rare in the densely populated and developed parts of the other provinces. In many areas within the wolfs worldwide range, populations have been decimated or completely extirpated, making Canada an important stronghold of the species.

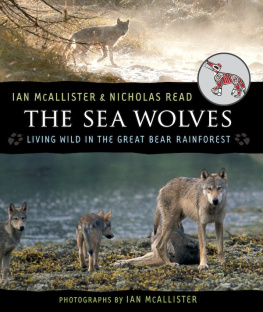

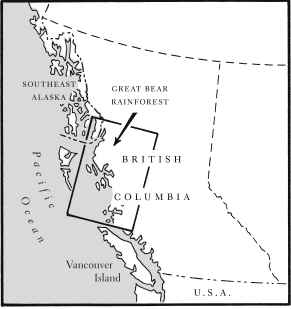

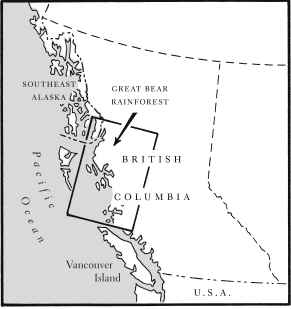

WHERE THE land meets the sea on British Columbias untamed Pacific Coast, a distinctive subspecies of gray wolf lives as it always has, comparatively unaffected by people. The Pacific Ocean overwhelmingly defines and influences the wolves environment, which is rich in human culture and natural history. Distributed on the mainland and nearby islands, these wolves swim in open ocean between landmasses as distant as thirteen kilometres (eight miles) contending with erratic winds, cold water, and strong tidal currents. Their physical features, behaviours, and pack traditions have been shaped by millennia of adaptation to the regions marine-dominated rain forest. Here wolves intermingle with other wide-ranging species, such as grizzly bears, killer whales, humpback whales, salmon, and migratory birds, many of which have been exterminated from much of their former ranges.

Among all the regions of North America where wolves still roam, the central and north coasts of British Columbia and the nearby offshore islands are ecologically unique. A network of islands, waterways, and mountains naturally fragments the land- and seascape. Yet the marine and the terrestrial are inextricably linked, providing the food and shelter that sustain coastal wolves. This remote ocean archipelago comprises North Americas most unusual and one of its most pristine wolf populations.

Many coastal wolves are island dwellers whose territories include groups of islands. Consequently, they are compelled to travel on land and swim between distant landmasses to make a living. Many of their prey, as well as other carnivores, such as black bears and grizzly bears, do the same. Although water barriers may constrain the movements of wolves and their prey, the ocean also augments the food available on land. In addition to feeding on deer, moose, and goat, wolves eat salmon, clams, crabs, and marine carrion such as beached seals, whales, and squid. In the fall, spawning salmon constitute a considerable part of the wolf diet as the fish return to the rivers and creeks of the rain forest, which are also used by wolves, bears, and other terrestrial species to travel among estuaries and to reach inland forests. Like bears, wolves transport marine nutrients from waterways into the regions ancient forests. Abandoned salmon carcasses, wolf feces, and wolf urine feed a diversity of organisms and fertilize coastal ecosystems.

Next page