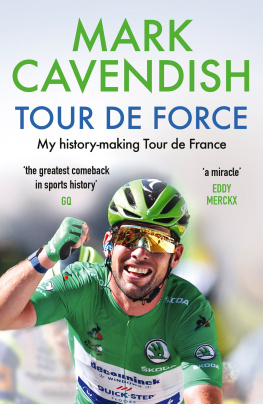

Book of the

TOUR DE FRANCE

For my mother and late father,

who bought me my first, second, third and fourth bikes

Historically, 2012 was a momentous year for the Tour de France. Bradley Wiggins claimed Britains first victory in the greatest sporting endurance race and then, in the autumn, came the gory exposure of Lance Armstrong and the US Postal and Discovery teams. Wigginss success is easy to write and read about: it is the story of one of the most individual and, in his own quiet way, charismatic personalities that modern-day sport has spawned. Conversely, the downfall of Armstrong is painful in the extreme: the revelations colour everything that has been penned about him over the last two decades.

Dave Brailsford, Team Skys principal, described the report by the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) which led to Armstrongs disgrace as having the effect of an atomic bomb on the sport and the shock waves from that 1,000-page document are ongoing and will be for years. The immediate effect was that Armstrong and his US Postal and Discovery teams were written out of the record books. His seven Tour titles were declared invalid and no other rider was promoted in his place. The world governing body, the UCI, heavily prompted by Tour de France race director Christian Prudhomme, decided that the period between 1999 and 2005 was so rife with doping and the use of Performance Enhancing Drugs (PED) that nobody among the main candidates in the General Classification (GC) could be entirely trusted. It was a harsh but understandable assessment.

Pat McQuaid, the UCI president, a little belatedly for some, declared that Lance Armstrong has no place in cycling history. In many obvious ways he is correct. However, David Millar, a rehabilitated former doper, takes a different view. He insists that the sport is changing for the better, and that the Texans remarkable hero to zero story should always be remembered for the message it conveys, not least for the scale of the fall when it came.

Personally, I am with Millar: we shouldnt attempt a wholesale re-writing of history with all-comers chiming in with their belated wise words after the event. The reality is that for the best part of a decade Lance Armstrong was the biggest star and personality in a worldwide sport. His was the name on everyones lips from dawn to dusk. So overwhelming was his presence, on the Tour de France especially, that it was impossible to go twenty minutes with colleagues without his name, and the did he/didnt he question, cropping up. I am struggling to think of an evening meal or long car journey which didnt end with such a debate. The verdict was usually the same: guilty, but untouchable until hard evidence was unearthed.

We know differently now. Not only about Armstrong, but also Tyler Hamilton, Floyd Landis, George Hincape, Michael Barry, David Zabriskie, Christian Vande Velde, Levi Leipheimer and Tom Danielson. North American sport has always been the world leader when it comes to using PEDs, even more so than the Soviet bloc in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s; all its major indigenous sports have been badly tainted over the years and many of the performances of their top athletes are as equally suspect as those from Eastern Europe. With hindsight it seems crass that the sport and the media were not more suspicious when Armstrongs rookie US Postal team started taking the Tour by storm and he beat not only specialists like Chris Boardman in Prologues but the worlds best climbers in mountain stages as well. But that was what happened and it does no harm to read within these pages what was written at the time and then fill in the gaps with what we now know to be fact.

One constant refrain, and a universal truth, is that it is the modern-day riders and sport who are left to pick up the pieces after the USADA report. Many contemporary riders have grown weary of apologising for the past and the beleaguered UCI have been pointing to a long list of big names they have brought to justice in recent years. Your view about the latter depends if you are a glass-half-full or half-empty individual. On one hand it can be seen as a very positive sign: no other sport chases and bans its poster boys like cycling does; but equally it is arguably a depressing sign that systemic doping still exists.

Everyone reacted to the USADA report in their own way; most, alas, retained a diplomatic silence and did nothing. Not so Sky and the Australian team Orica GreenEdge who both decided to be proactive. Others might follow. At Sky, Brailsford was staggered by the sheer scale of the doping revealed in the testimonies given to USADA by the riders. He decided to go back to basics and re-inforce Skys zero tolerance policy to any kind of doping incident, whether past or present.

While confident that his riders would pass muster, Brailsford was shaken to the core that recent team member Michael Barry was one of those who gave evidence of his own doping history as well as Armstrongs. Barry had denied any involvement when interviewed by Brailsford before joining the team. Less than two months after Bradley Wigginss remarkable success in Paris, Brailsford personally re-interviewed all eighty members of the Sky squad and then required them to sign a form denying any doping past. Within a matter of days directeur sportif Stephen de Jong and race coach Bobby Julich had departed, followed by senior directeur sportif Sean Yates, who suddenly announced his retirement. Sky insist, though, that Yates made no admission to any doping incident when interviewed. It was a traumatic time for the team when they should have been basking in the afterglow of their success but it was a stance Brailsford was determined to take, even if it hinged on fleeting associations with doping ten or fifteen years before. His priority was to maintain the integrity of Sky so that people can believe in what they see and celebrate accordingly. Which brings us rather belatedly to the story of how Bradley Wiggins, aided and abetted by his team, won the 2012 Tour de France.

The day-by-day story of Wigginss remarkable success, and the impact on the British public, is captured in these pages. But as you would expect with such a fascinating and complicated individual, that is scarcely half the tale. The origins and motivation for Wigginss Tour de France triumph go back a long way with many of the key moments unobserved and unrecorded by the general sporting public.

When Dave Brailsford started to put Team Sky together, straight after the Beijing Olympics, he gave his squad the mission statement of winning the GC title in the Tour de France within five years. He attracted widespread ridicule, not least in the Continental cycling press, who mistook goal-setting for arrogance. Their sniggers could be heard after the 2010 Tour when Wiggins, having been expensively and controversially acquired by Team Sky from Garmin, flopped so badly during his first race as a team leader that he finished among the also-rans. For a man who had cruised home in fourth position twelve months earlier with very little specific training, it was tantamount to disaster. Physically there was one extenuating circumstance, though it is to Wigginss credit that it scarcely warranted a mention at the time. Wiggins pulled a groin muscle when crashing on stage two and required painkilling injections most days, which is not an ideal situation when you have over 3,500km of rugged terrain to negotiate as well as some of the most iconic climbs in cycling.