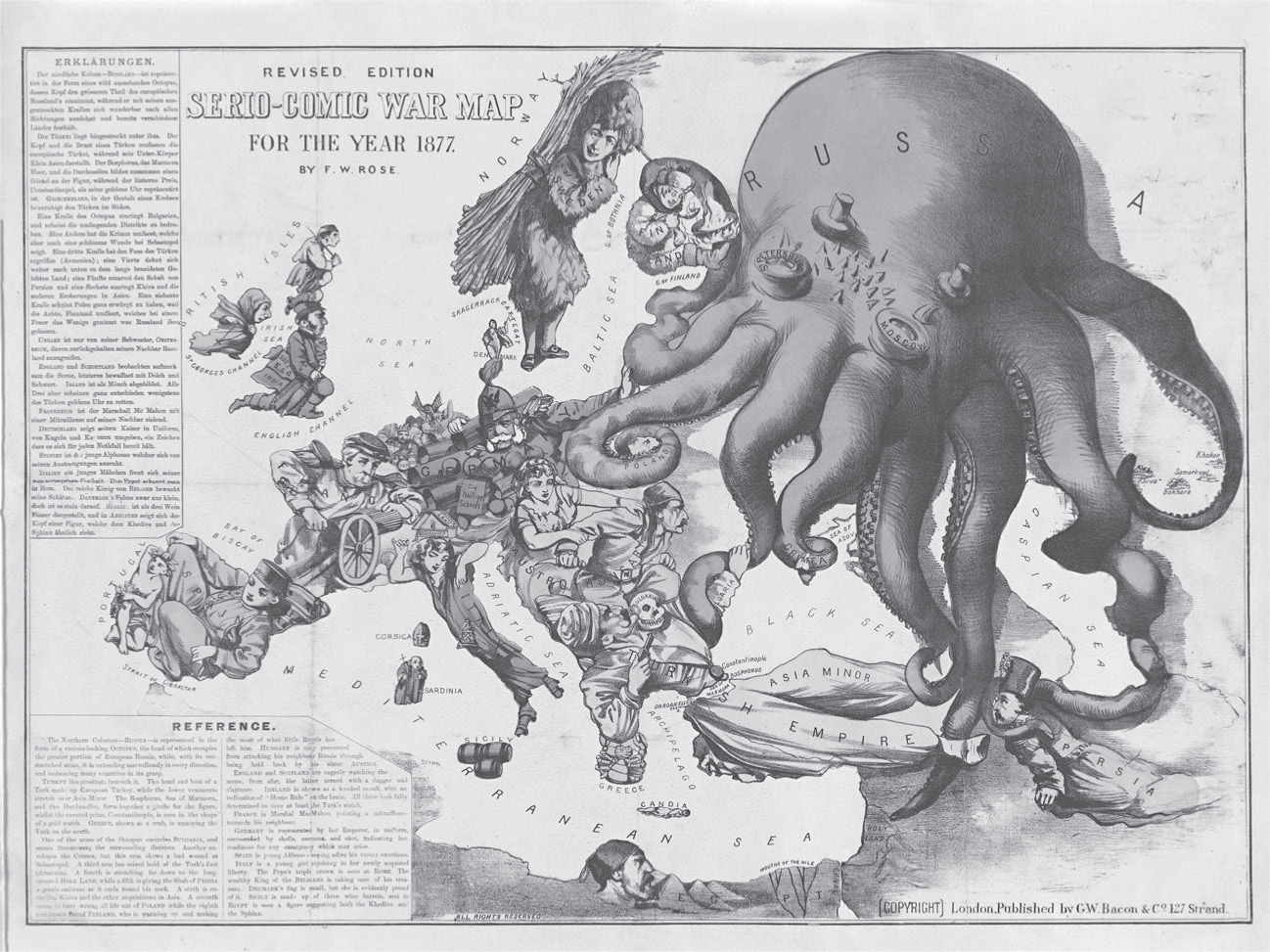

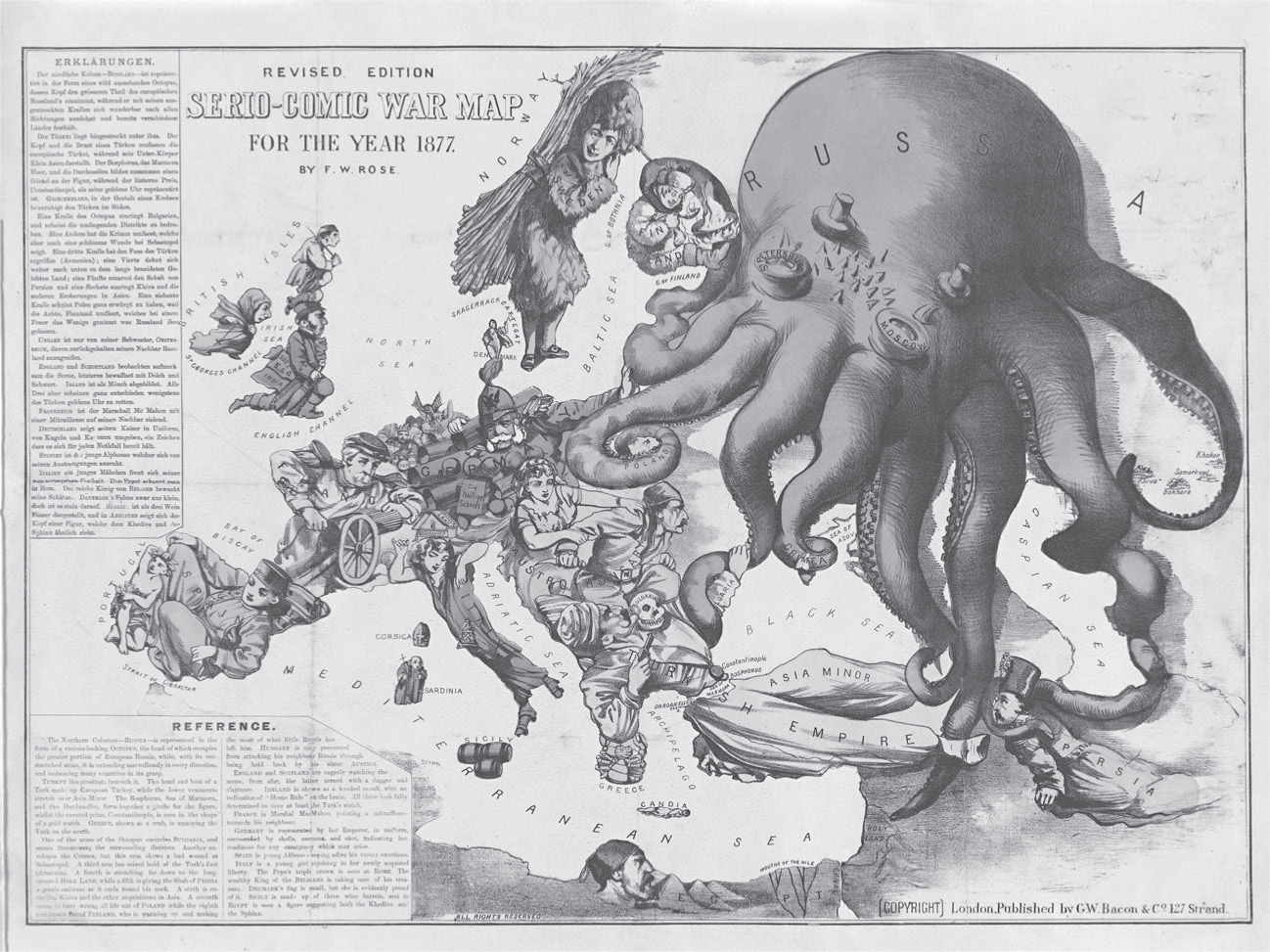

From the nineteenth century, the international press saw Russia as a furious bear, shaking its paws, baring its fangs, and waiting to be unleashed on its neighbours. Which is more frightening? The bear on the rampage, or the octopus spreading its tentacles, oozing through gaps and blending in with its surroundings? A well-known comic map of 1877 has Russia as an octopus. The other countries of Europe are drawn as human characters.

Mark B. Smith

The Russia Anxiety

And How History Can Resolve It

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published 2019

Copyright Mark B. Smith, 2019

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN: 978-0-241-31280-3

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed orpublicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowedunder the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyrightlaw. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors andpublishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

For Laura and Sonia

Maps

1. EXPANSION (1) The emergence of Russia: Moscow was founded in 1147. At this time, other older principalities of Rus, notably Kiev, had been expanding and contracting for centuries, and other proto-states, such as the Republic of Novgorod and Volga Bulgaria, were regional powers. Borders were never fixed, national identities were far from primordial, and the medieval East Slavic world was multipolar.

2. EXPANSION (2) The gathering of Russia: despite its late emergence and devastation at the hands of the Mongols in 1240, Muscovy became the centre of East Slavic civilization in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, expanding its borders with more durable success than previous or associated expansionary powers in the region, such as Kievan Rus, had managed to do.

3. EXPANSION (3) The vastness of Russia: the Russian Empire continued to expand, reaching its greatest extent, covering one-sixth of the worlds land surface, by the time of the outbreak of the First World War. At this point it was approximately the same size as the British Empire, though the British Empire continued to grow after 1918.

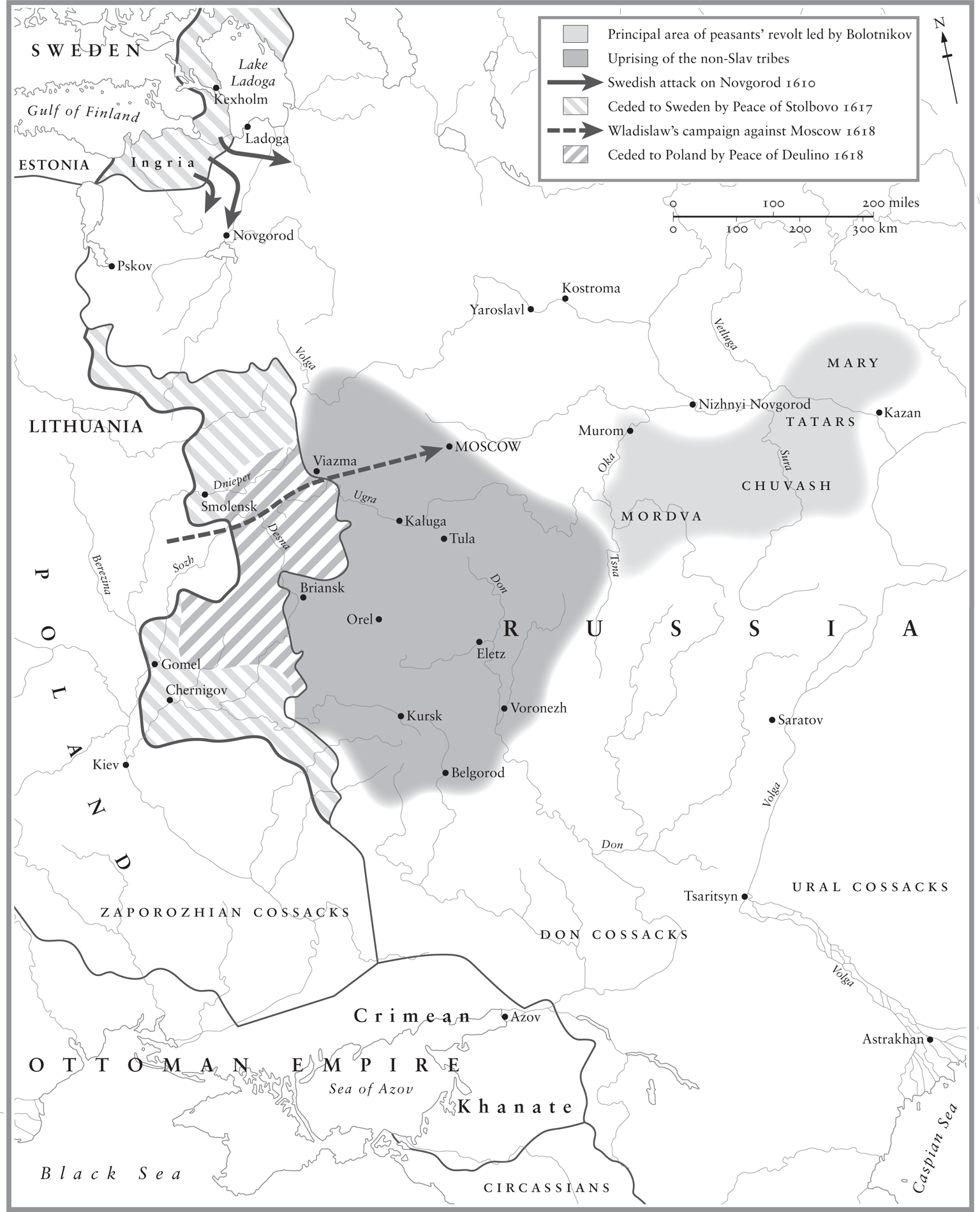

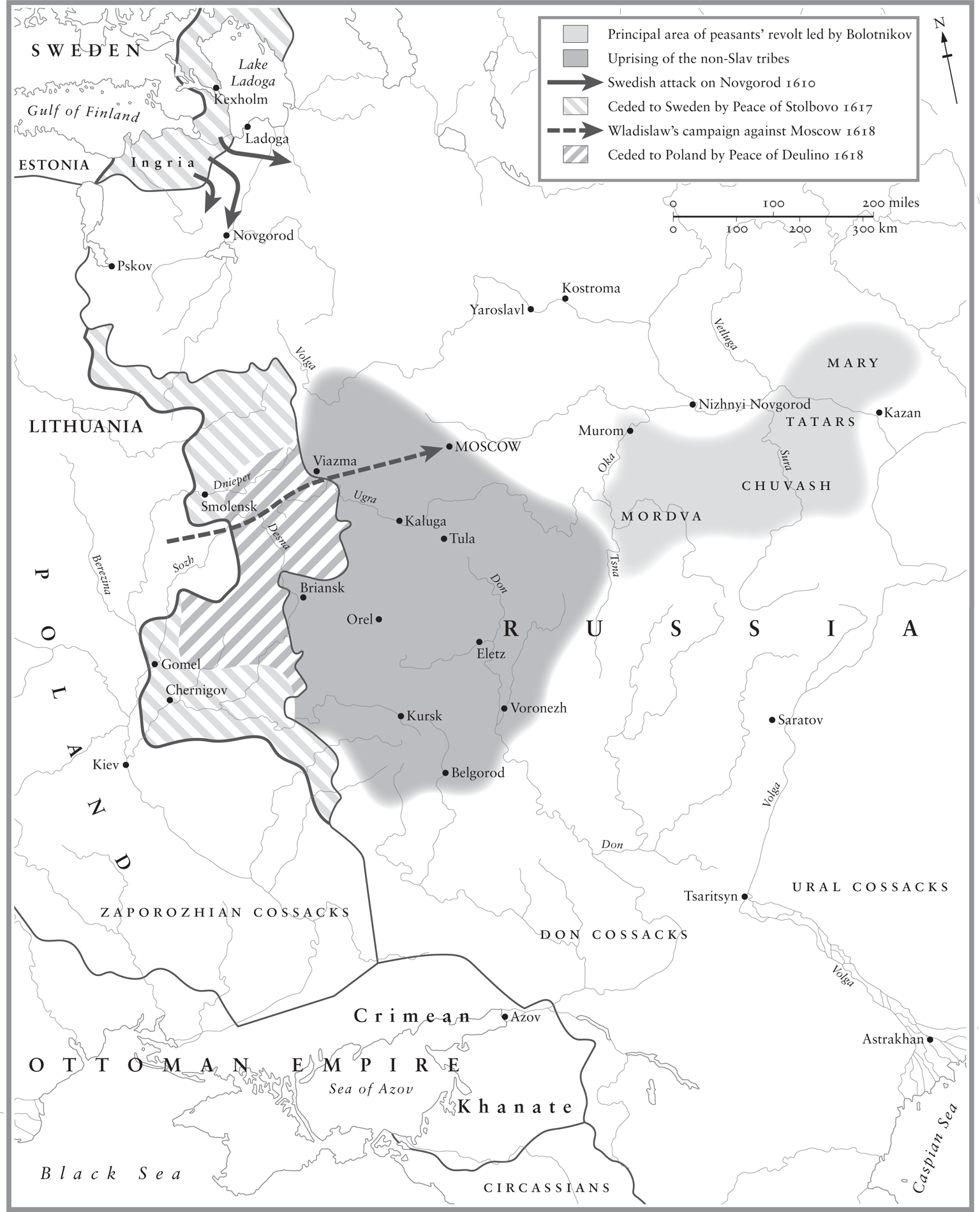

4. PRESSURE (1) From the north and west: in its various incarnations Russia has faced elimination at the hands of foreign invaders. Moments of total crisis included the invasion and occupation by the Mongols that began in 1240, the invasion by Sweden in 1708, the attack by France in 1812 and the assault by Germany in 1941. One of the worst moments came during the Time of Troubles at the start of the seventeenth century, when the Swedes invaded, the Poles briefly occupied Moscow, and famine and dynastic crisis converged.

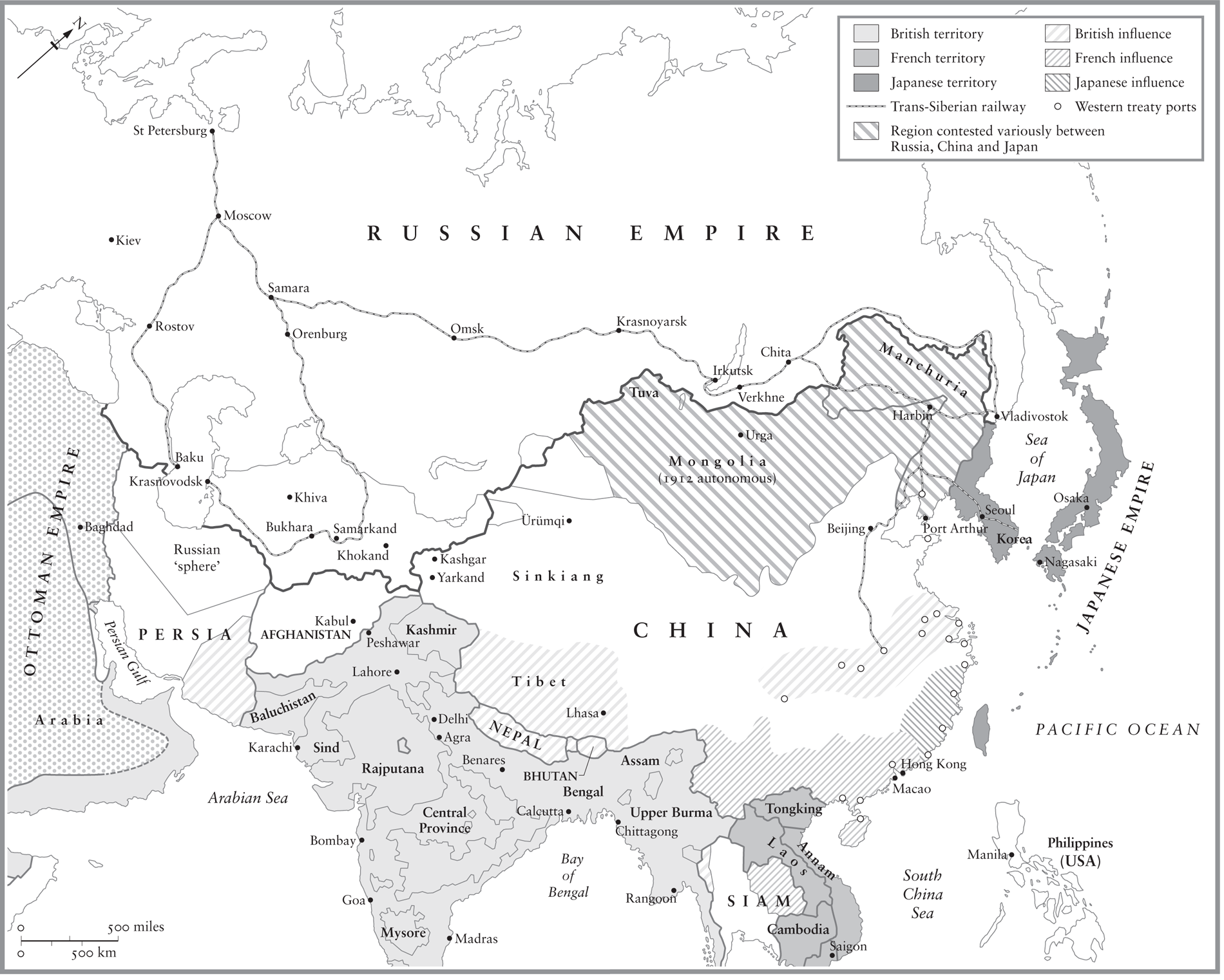

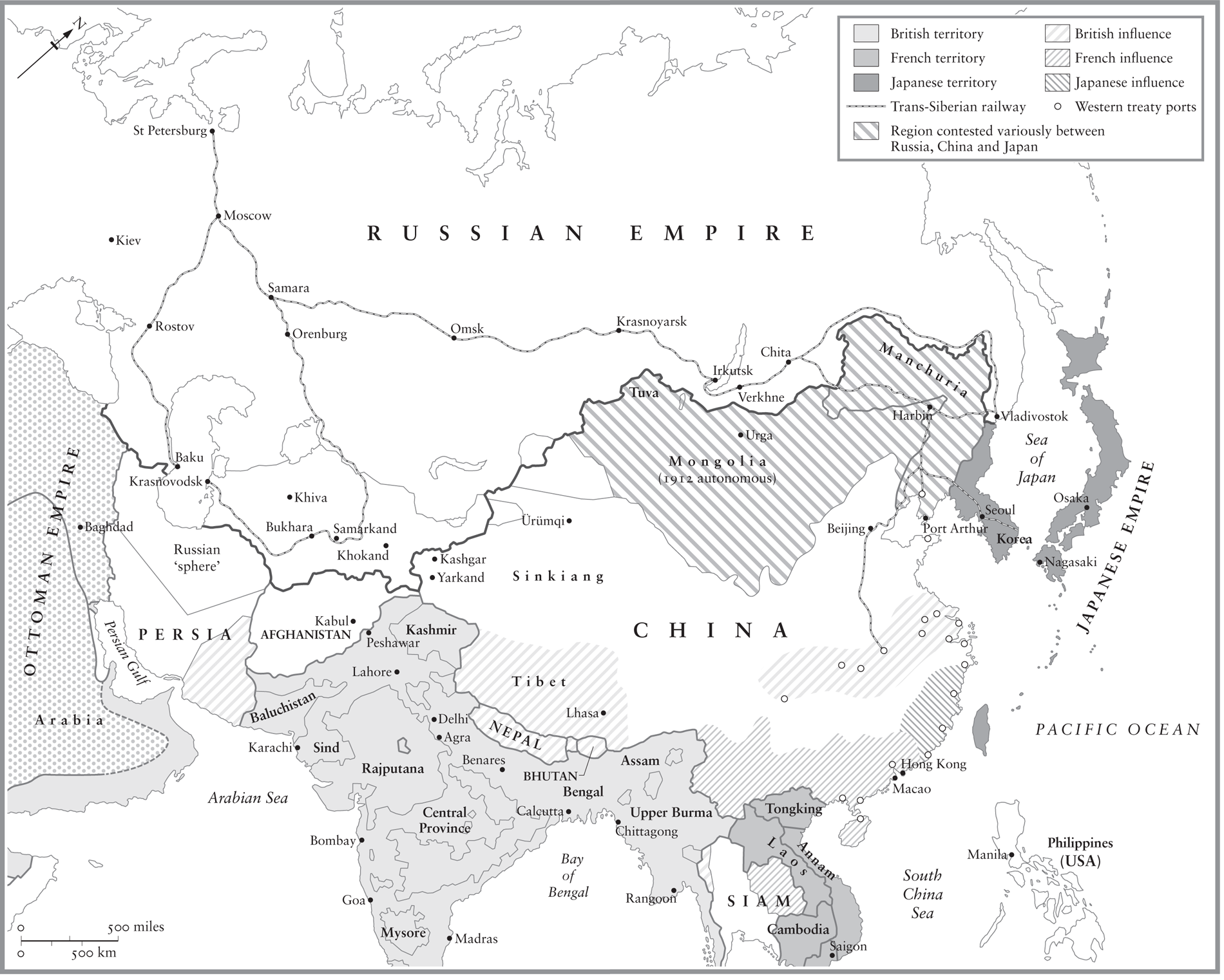

5. PRESSURE (2) From the east and south: the sheer length of its borders gives Russias policymakers unique strategic and defensive challenges. In the nineteenth century, Russia sensed threats from the Ottoman Empire in Asia, from the British in India and Afghanistan, and from the Japanese as well as from the whole range of European, American and Asian empires.

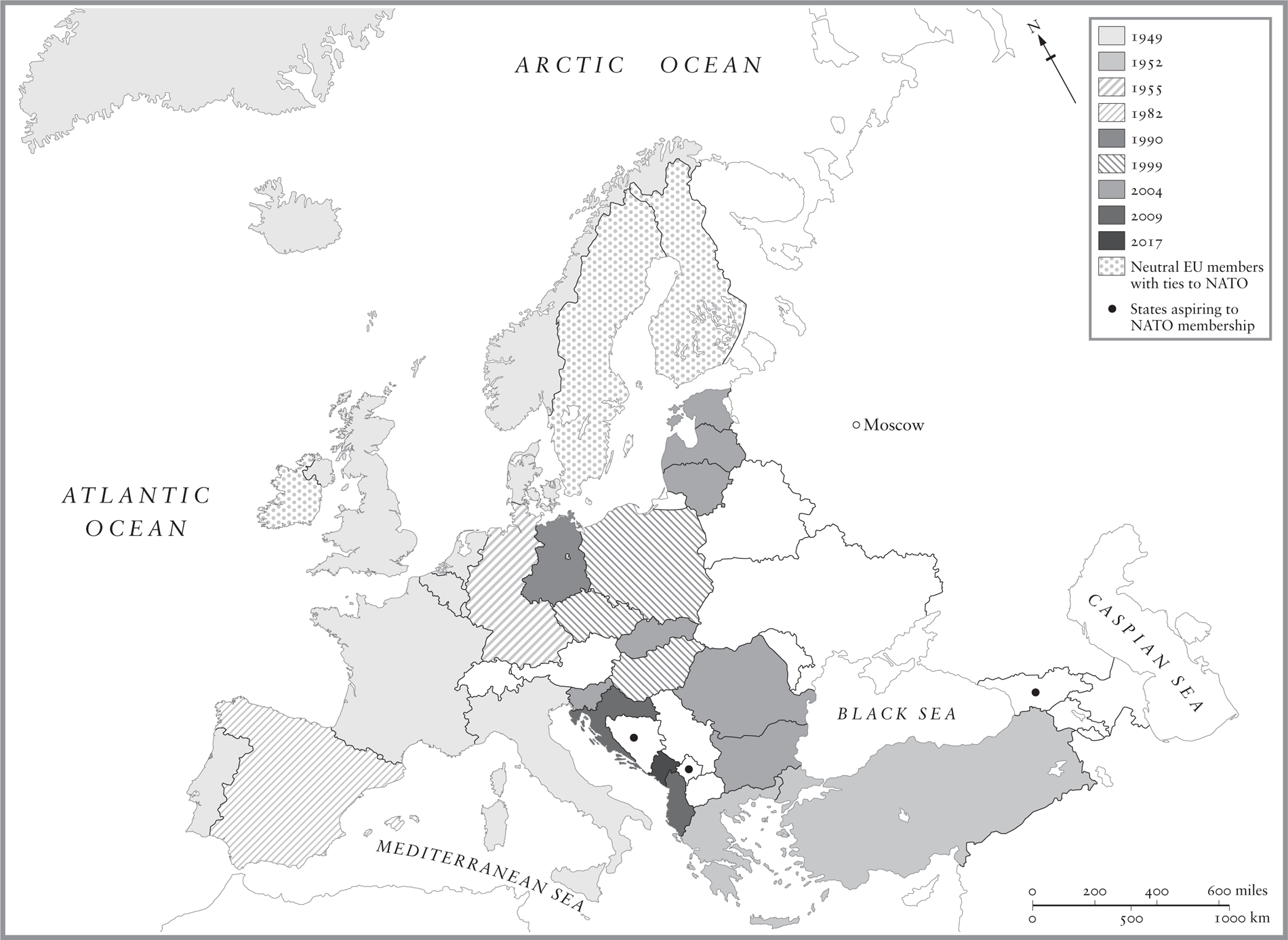

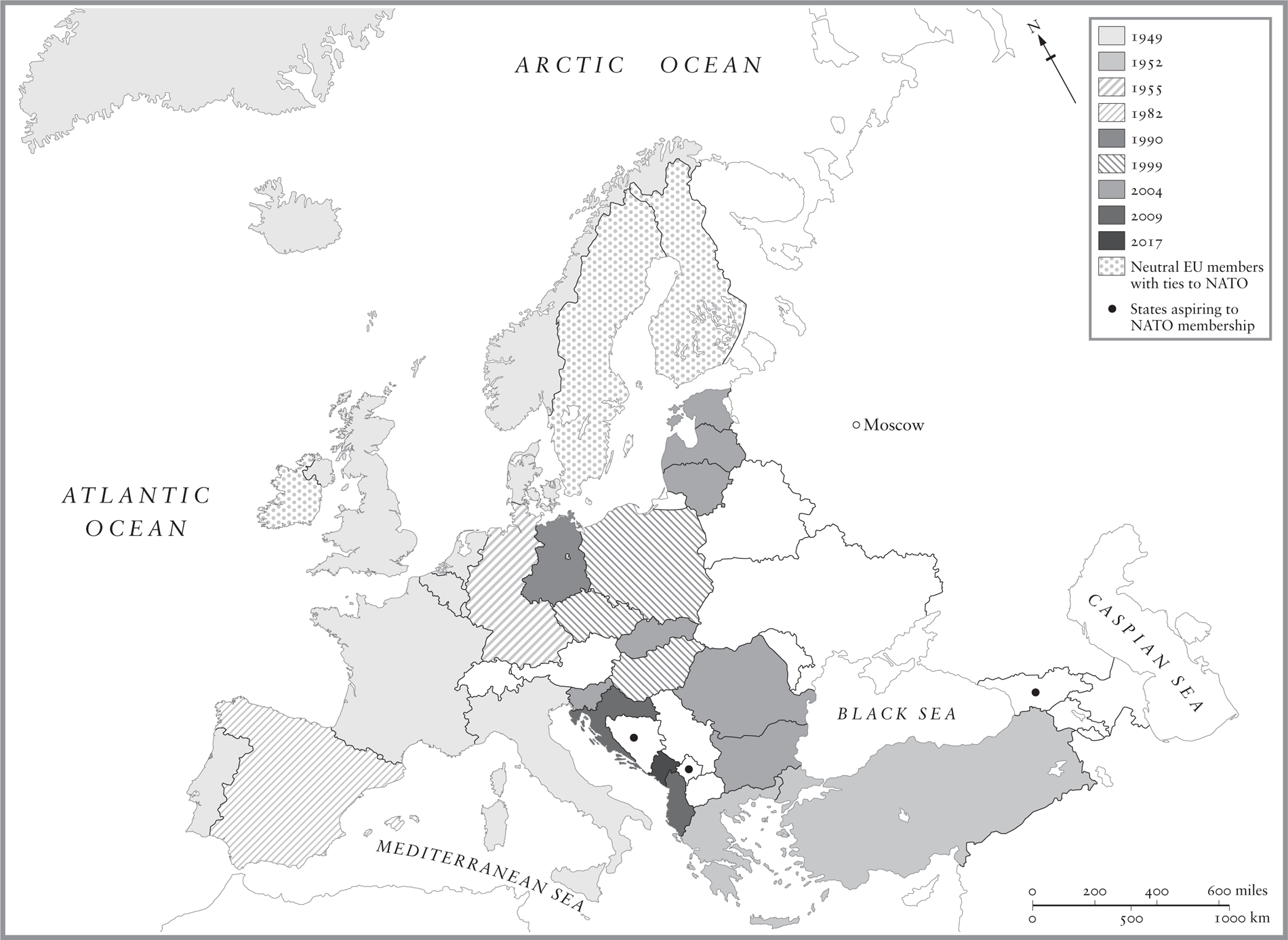

6. PRESSURE (3) Twenty-first century encirclement? The view from Moscow is of Washington and Brussels getting ever closer, with NATO historically an anti-Moscow alliance possessing a strategy of expansion, and the members of the EU defining themselves as European in distinction to non-EU states that are also located in Europe.

Preface

I teach Russian history for a living, and I sometimes ask a class to tell me the first thing they think of when they hear the word Russia. Students suspect a trick question and turn their gaze towards the middle distance. But whats the trick?

In the new age of Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin I asked a group of students a slightly different question from the one above: what they thought when they heard the name Putin. The image that one of them put forward was precisely what the media presented: a villain from a James Bond movie. His policies were violent and expansionist; his rule was arbitrary and coercive. He ran a kleptocracy and a mafia state based on a veneer of Russian nationalism. It was a house of cards, ready to fall. But then the student did what many excellent students do: mid-statement, uninterrupted, he pulled himself up short, breathed out and suddenly changed direction. He struggled to find coherence in terms such as mafia state. Sensing the perils of received wisdom, he wondered if he was only saying what he was supposed to say, and he set about adjusting his position in full view of the rest of the class.

The question was not only about Russia, or about Putin: it was about the limits of how we understand the world around us. After all, observers had for years told different stories about Putins Russia. For some, Putin had reshaped and modernized his country. Under his leadership, Russia emerged from the chaos and misery of the 1990s. He established a stable economy that was more flexible and open than before, and that raised living standards, at least in metropolitan centres, even after oil prices had long stopped rising. Presenting himself as dignified, articulate and decisive, he also stabilized the countrys politics. Many Russians led normal lives, forming reasonable ambitions and plausible plans to realize them. It was easy enough to understand Putins popularity. Was this another aspect of the truth?

I teach history, as Ive said, and so the problems I discuss with my students concern the past, even if the conversation has turned towards the present day. When it comes to Russia, history shapes our imaginations and defines our misperceptions. Was the present really the consequence of the past? Had Vladimir Putin made Russia modern, or had he allowed it to revert to type? In the age of Trump and Putin, did the Wests Russia crisis come out of the past, or did it point towards a uniquely dangerous future?

Every day brought a new headline describing Russia as a hostile foreign power, with talk of annexation, fighting, mischief, hacking, hit jobs, sanctions, corruption and a short road to war. News programmes led with encroachments on airspace, interventions in elections and nerve poison in the medieval English town of Salisbury. In the years that followed Vladimir Putins third election victory in 2012, Russia was cast as an extraordinary danger, and its president became Public Enemy Number 1.

Next page

1. EXPANSION (1) The emergence of Russia: Moscow was founded in 1147. At this time, other older principalities of Rus, notably Kiev, had been expanding and contracting for centuries, and other proto-states, such as the Republic of Novgorod and Volga Bulgaria, were regional powers. Borders were never fixed, national identities were far from primordial, and the medieval East Slavic world was multipolar.

1. EXPANSION (1) The emergence of Russia: Moscow was founded in 1147. At this time, other older principalities of Rus, notably Kiev, had been expanding and contracting for centuries, and other proto-states, such as the Republic of Novgorod and Volga Bulgaria, were regional powers. Borders were never fixed, national identities were far from primordial, and the medieval East Slavic world was multipolar. 2. EXPANSION (2) The gathering of Russia: despite its late emergence and devastation at the hands of the Mongols in 1240, Muscovy became the centre of East Slavic civilization in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, expanding its borders with more durable success than previous or associated expansionary powers in the region, such as Kievan Rus, had managed to do.

2. EXPANSION (2) The gathering of Russia: despite its late emergence and devastation at the hands of the Mongols in 1240, Muscovy became the centre of East Slavic civilization in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, expanding its borders with more durable success than previous or associated expansionary powers in the region, such as Kievan Rus, had managed to do. 3. EXPANSION (3) The vastness of Russia: the Russian Empire continued to expand, reaching its greatest extent, covering one-sixth of the worlds land surface, by the time of the outbreak of the First World War. At this point it was approximately the same size as the British Empire, though the British Empire continued to grow after 1918.

3. EXPANSION (3) The vastness of Russia: the Russian Empire continued to expand, reaching its greatest extent, covering one-sixth of the worlds land surface, by the time of the outbreak of the First World War. At this point it was approximately the same size as the British Empire, though the British Empire continued to grow after 1918. 4. PRESSURE (1) From the north and west: in its various incarnations Russia has faced elimination at the hands of foreign invaders. Moments of total crisis included the invasion and occupation by the Mongols that began in 1240, the invasion by Sweden in 1708, the attack by France in 1812 and the assault by Germany in 1941. One of the worst moments came during the Time of Troubles at the start of the seventeenth century, when the Swedes invaded, the Poles briefly occupied Moscow, and famine and dynastic crisis converged.

4. PRESSURE (1) From the north and west: in its various incarnations Russia has faced elimination at the hands of foreign invaders. Moments of total crisis included the invasion and occupation by the Mongols that began in 1240, the invasion by Sweden in 1708, the attack by France in 1812 and the assault by Germany in 1941. One of the worst moments came during the Time of Troubles at the start of the seventeenth century, when the Swedes invaded, the Poles briefly occupied Moscow, and famine and dynastic crisis converged. 5. PRESSURE (2) From the east and south: the sheer length of its borders gives Russias policymakers unique strategic and defensive challenges. In the nineteenth century, Russia sensed threats from the Ottoman Empire in Asia, from the British in India and Afghanistan, and from the Japanese as well as from the whole range of European, American and Asian empires.

5. PRESSURE (2) From the east and south: the sheer length of its borders gives Russias policymakers unique strategic and defensive challenges. In the nineteenth century, Russia sensed threats from the Ottoman Empire in Asia, from the British in India and Afghanistan, and from the Japanese as well as from the whole range of European, American and Asian empires. 6. PRESSURE (3) Twenty-first century encirclement? The view from Moscow is of Washington and Brussels getting ever closer, with NATO historically an anti-Moscow alliance possessing a strategy of expansion, and the members of the EU defining themselves as European in distinction to non-EU states that are also located in Europe.

6. PRESSURE (3) Twenty-first century encirclement? The view from Moscow is of Washington and Brussels getting ever closer, with NATO historically an anti-Moscow alliance possessing a strategy of expansion, and the members of the EU defining themselves as European in distinction to non-EU states that are also located in Europe.