Figes - Natashas dance: a cultural history of Russia

Here you can read online Figes - Natashas dance: a cultural history of Russia full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Russia, year: 2002, publisher: Henry Holt and Co.;Picador, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Natashas dance: a cultural history of Russia: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Natashas dance: a cultural history of Russia" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Figes: author's other books

Who wrote Natashas dance: a cultural history of Russia? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Natashas dance: a cultural history of Russia — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Natashas dance: a cultural history of Russia" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For Lydia and Alice

List of Illustrations and Photographic Acknowledgements

Every effort has been made to contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be happy to make good in future editions any errors or omissions brought to their attention.

CHAPTER OPENERS

TEXT ILLUSTRATIONS

Notes on the Maps and Text

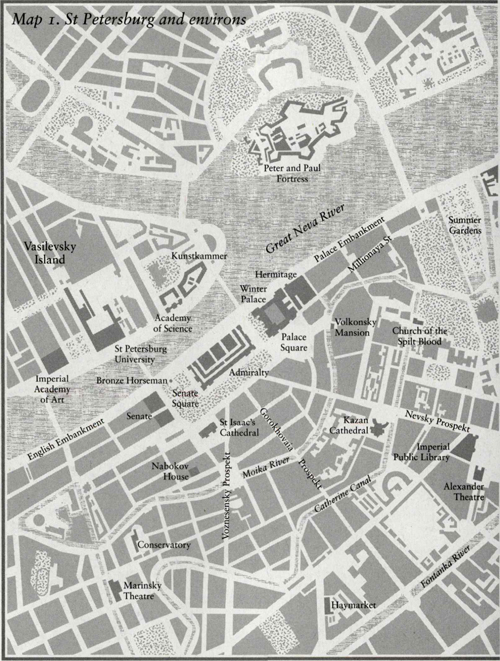

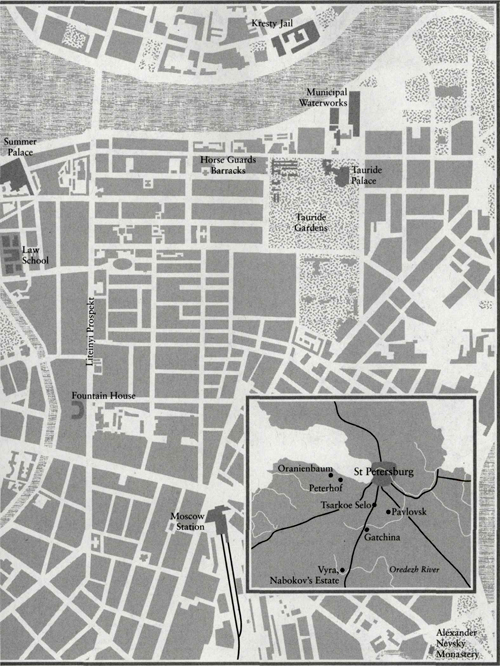

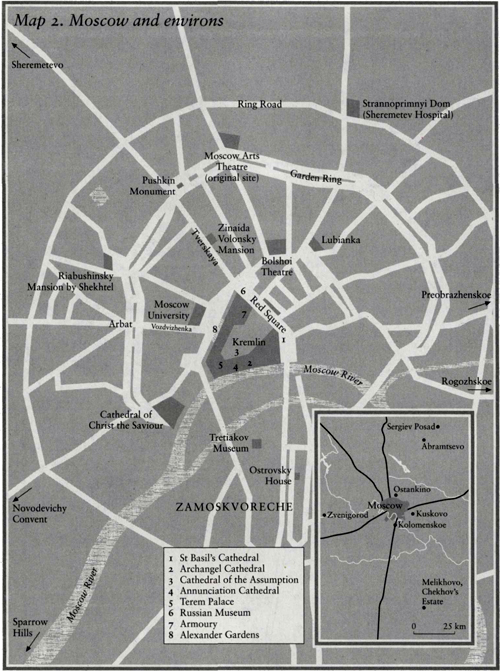

MAPS

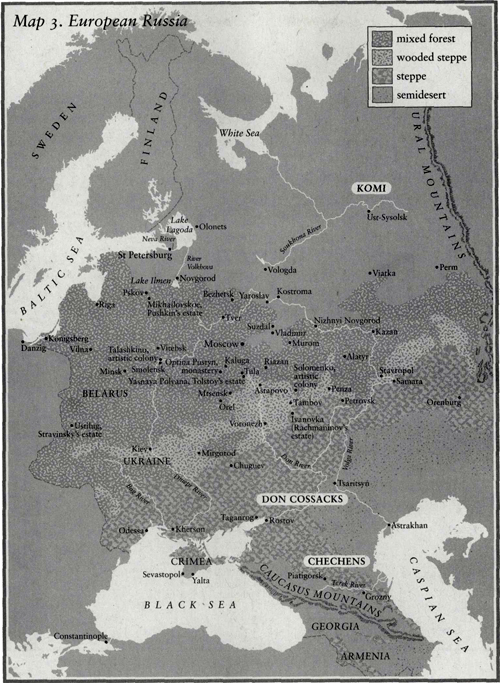

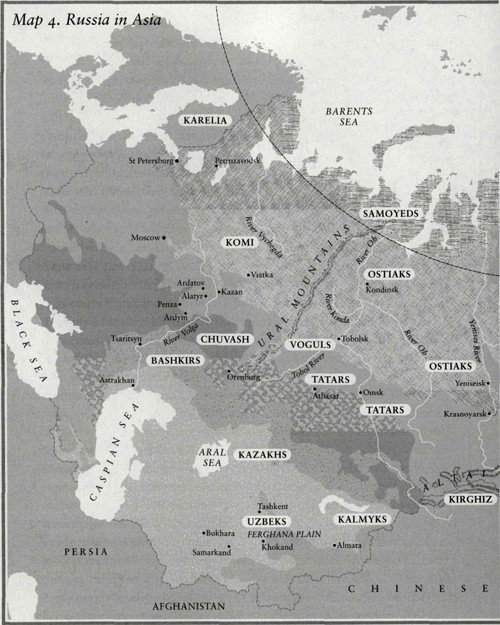

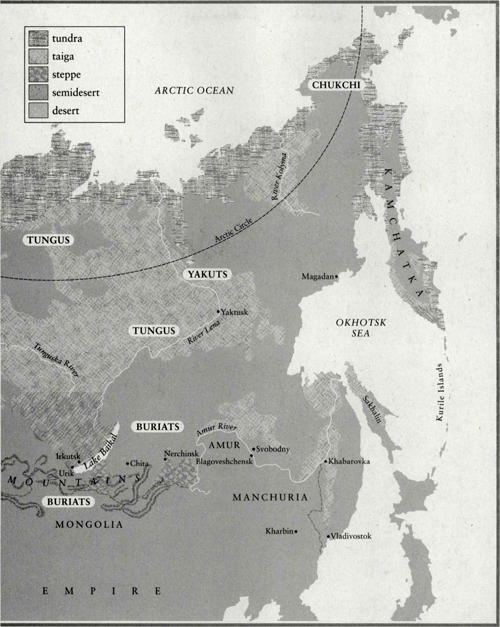

Place names indicated in the maps are those used in Russia before 1917. Soviet names are given in the text where appropriate. Since 1991, most Russian cities have reverted to their pre-revolutionary names.

RUSSIAN NAMES

Russian names are spelled in this book according to the standard (Library of Congress) system of transliteration, but common English spellings of well-known Russian names (Tolstoy and Tchaikovsky, or the Tsar Peter, for example) are retained. To aid pronounciation some Russian names (Vasily, for example) are slightly changed (in this case, from Vasilii).

DATES

From 1700 until 1918 Russia adhered to the Julian calendar, which ran thirteen days behind the Gregorian calendar in use in western Europe. Dates in this book are given according to the Julian calendar until February 1918, when Soviet Russia switched to the Gregorian calendar.

USE OF METRIC

All measurements of distance, weight and area are given in the metric system.

NOTES

Literary works cited in this book are, wherever possible, from an English-language translation available in bookshops.

Maps

INTRODUCTION

In Tolstoys War and Peace there is a famous and rather lovely scene where Natasha Rostov and her brother Nikolai are invited by their Uncle (as Natasha calls him) to his simple wooden cabin at the end of a days hunting in the woods. There the noble-hearted and eccentric Uncle lives, a retired army officer, with his housekeeper Anisya, a stout and handsome serf from his estate, who, as it becomes clear from the old mans tender glances, is his unofficial wife. Anisya brings in a tray loaded with homemade Russian specialities: pickled mushrooms, rye-cakes made with buttermilk, preserves with honey, sparkling mead, herb-brandy and different kinds of vodka. After they have eaten, the strains of a balalaika become audible from the hunting servants room. It is not the sort of music that a countess should have liked, a simple country ballad, but seeing how his niece is moved by it, Uncle calls for his guitar, blows the dust off it, and with a wink at Anisya, he begins to play, with the precise and accelerating rhythm of a Russian dance, the well-known love song, Came a maiden down the street. Though Natasha has never before heard the folk song, it stirs some unknown feeling in her heart. Uncle sings as the peasants do, with the conviction that the meaning of the song lies in the words and that the tune, which exists only to emphasize the words, comes of itself. It seems to Natasha that this direct way of singing gives the air the simple charm of birdsong. Uncle calls on her to join in the folk dance.

Now then, niece! he exclaimed, waving to Natasha the hand that had just struck a chord.

Natasha threw off the shawl from her shoulders, ran forward to face Uncle, and setting her arms akimbo, also made a motion with her shoulders and struck an attitude.

Where, how, and when had this young countess, educated by an migre French governess, imbibed from the Russian air she breathed that spirit, and obtained that manner which the pas de chle would, one would have supposed, long ago have effaced? But the spirit and the movements were those inimitable and unteachable Russian ones that Uncle had expected of her. As soon as she had struck her pose and smiled triumphantly, proudly, and with sly merriment, the fear that had at first seized Nikolai and the others that she might not do the right thing was at an end, and they were all already admiring her.

She did the right thing with such precision, such complete precision, that Anisya Fyodorovna, who had at once handed her the handkerchief she needed for the dance, had tears in her eyes, though she laughed as she watched this slim, graceful countess, reared in silks and velvets and so different from herself, who yet was able to understand all that was in Anisya and in Anisyas father and mother and aunt, and in every Russian man and woman.

What enabled Natasha to pick up so instinctively the rhythms of the dance? How could she step so easily into this village culture from which, by social class and education, she was so far removed? Are we to suppose, as Tolstoy asks us to in this romantic scene, that a nation such as Russia may be held together by the unseen threads of a native sensibility? The question takes us to the centre of this book. It calls itself a cultural history. But the elements of culture which the reader will find here are not just great creative works like War and Peace but artefacts as well, from the folk embroidery of Natashas shawl to the musical conventions of the peasant song. And they are summoned, not as monuments to art, but as impressions of the national consciousness, which mingle with politics and ideology, social customs and beliefs, folklore and religion, habits and conventions, and all the other mental bric--brac that constitute a culture and a way of life. It is not my argument that art can serve the purpose of a window on to life. Natashas dancing scene cannot be approached as a literal record of experience, though memoirs of this period show that there were indeed noblewomen who picked up village dances in this way. But art can be looked at as a record of belief in this case, the writers yearning for a broad community with the Russian peasantry which Tolstoy shared with the men of 1812, the liberal noblemen and patriots who dominate the public scenes of War and Peace.

Russia invites the cultural historian to probe below the surface of artistic appearance. For the past two hundred years the arts in Russia have served as an arena for political, philosophical and religious debate in the absence of a parliament or a free press. As Tolstoy wrote in A Few Words on War and Peace (1868), the great artistic prose works of the Russian tradition were not novels in the European sense. They were huge poetic structures for symbolic contemplation, not unlike icons, laboratories in which to test ideas; and, like a science or religion, they were animated by the search for truth. The overarching subject of all these works was Russia its character, its history, its customs and conventions, its spiritual essence and its destiny. In a way that was extraordinary, if not unique to Russia, the countrys artistic energy was almost wholly given to the quest to grasp the idea of its nationality. Nowhere has the artist been more burdened with the task of moral leadership and national prophecy, nor more feared and persecuted by the state. Alienated from official Russia by their politics, and from peasant Russia by their education, Russias artists took it upon themselves to create a national community of values and ideas through literature and art. What did it mean to be a Russian? What was Russias place and mission in the world? And where was the true Russia? In Europe or in Asia? St Petersburg or Moscow? The Tsars empire or the muddy one-street village where Natashas Uncle lived? These were the accursed questions that occupied the mind of every serious writer, literary critic and historian, painter and composer, theologian and philosopher in the golden age of Russian culture from Pushkin to Pasternak. They are the questions that lie beneath the surface of the art within this book. The works discussed here represent a history of ideas and attitudes concepts of the nation through which Russia tried to understand itself. If we look carefully, they may become a window on to a nations inner life.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Natashas dance: a cultural history of Russia»

Look at similar books to Natashas dance: a cultural history of Russia. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Natashas dance: a cultural history of Russia and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.