The research for this book took place over many years and thanks are due to a large number of people.

In the early stages of research Helen Rappaport helped me to compile a working bibliography from the potentially endless list of books, published memoirs, diaries and letters by participants in the Crimean War. She also gave invaluable advice on the social history of the war, sharing information from her own research for No Place for Ladies: The Untold Story of Women in the Crimean War .

At the National Army Museum in London I am grateful to Alastair Massie, whose own works, The National Army Museum Book of the Crimean War: The Untold Stories and A Most Desperate Undertaking: The British Army in the Crimea, 185456 , were an inspiration to my own. I gratefully acknowledge the permission of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II to make use of the materials from the Royal Archives, and am thankful to Sophie Gordon for her advice on the photographs of the Royal Collection at Windsor. In the Basbanlik Osmanlik Archive in Istanbul, I was helped by Murat Siviloglu and Melek Maksudoglu, and in the Russian State Military History Archive in Moscow by Luisa Khabibulina.

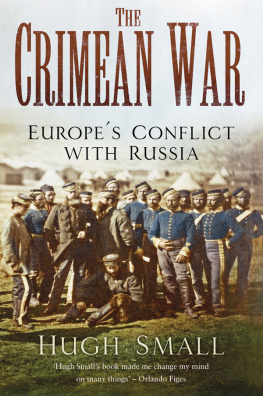

Various people commented on all or sections of the draft Norman Stone, Sean Brady, Douglas Austin, Tony Margrave, Mike Hinton, Miles Taylor, Dominic Lieven and Mark Mazower and I am grateful to them all. Douglas Austin and Tony Margrave, in particular, were a mine of information on various military aspects. Thanks are also due to Mara Kozelsky for allowing me to read the typescript of her then unfinished book on the Crimea, to Metin Kunt and Onur nul for help on Turkish matters, to Edmund Herzig on Armenian affairs, toLucy Riall for advice on Italy, to Joanna Bourke for her thoughts on military psychology, to Antony Beevor for his help on the hussars, to Ross Belson for background information on the resignation of Sidney Herbert, to Keith Smith for his generous donation of the extraordinary photograph Old Scutari and Modern skdar by James Robertson, and to Hugh Small, whose book The Crimean War: Queen Victorias War with the Russian Tsars made me change my mind on many things.

As always, I am indebted to my family, to my wife, Stephanie, and our daughters, Lydia and Alice, who could never quite believe that I was writing a war book but indulged my interests nonetheless; to my wonderfully supportive agent, Deborah Rogers, and her superb team at Rogers, Coleridge and White, especially Ruth McIntosh, who talks me through my VAT returns, and to Melanie Jackson in New York; to Cecilia Mackay for her thoughtful work on the illustrations; to Elizabeth Stratford for the copy-editing; to Alan Gilliland for the excellent maps; and above all to my two great editors, Simon Winder at Penguin and Sara Bershtel at Metropolitan.

Peasant Russia, Civil War:

The Volga Countryside in Revolution, 1917 1921

A Peoples Tragedy:

The Russian Revolution, 1891 1924

Interpreting the Russian Revolution:

The Language and Symbols of 1917

(with Boris Kolonitskii)

Natashas Dance:

A Cultural History of Russia

The Whisperers:

Private Life in Stalins Russia

ORLANDO FIGES is the author of The Whisperers, Natashas Dance, and A Peoples Tragedy, which have been translated into over twenty languages. The recipient of the Wolfson History Prize and the Los Angeles Times Book Award, among others, Figes is a professor of history at Birkbeck College, University of London.

The end of the Crimean War was marked by modest festivities in Britain. There was general disappointment that peace had come before the troops had scored a major victory to equal that of the French at Sevastopol and that they had failed to carry out a broader war against Russia. Mixed with this sense of failure was a feeling of outrage and national shame at the blunders of the government and military authorities. I own that peace rather sticks in my throat, Queen Victoria noted in her journal on 11 March, and so it does in that of the whole Nation. There was no great victory parade in London, no official ceremony to welcome home the troops, who arrived at Woolwich looking very sunburnt, according to the Queen. Watching several boatloads of soldiers disembark on 13 March, she thought they were the picture of real fighting men, such fine tall strong men, some strikingly handsome all with such proud, noble, soldier-like bearing . They all had long beards, and were heavily laden with large knapsacks, their cloaks and blankets on the top, canteens and full haversacks, and carrying their muskets.

But if there were no joyous celebrations, there were memorials literally hundreds of commemorative plaques and monuments, paid for in the main by groups of private individuals and erected in memory of lost and fallen soldiers in church graveyards, regimental barracks, hospitals and schools, city halls and museums, on town squares and village greens across the land. Of the 98,000 British soldiers and sailors sent to the Crimea, more than one in five did not return: 20,813 men died in the campaign, 80 per cent of them from sickness or disease.

Reflecting this public sense of loss and admiration for the suffering troops, the government commissioned a Guards Memorial tocommemorate the heroes of the Crimean War. John Bells massive ensemble three bronze Guardsmen (Coldstream, Fusilier and Grenadier) cast from captured Russian cannon and standing guard beneath the classical figure of Honour was unveiled on Waterloo Place at the intersection of Lower Regent Street and Pall Mall in London in 1861. Opinion was divided on the monuments artistic qualities. Londoners referred to the figure of Honour as the quoits player because the oak-leaf coronels in her outstretched arms resembled the rings used in that game. Many thought the monument lacked the grace and beauty needed for a site of such significance (Count Gleichen later said that it looked best in the fog). But its symbolic impact was unprecedented. It was the first war memorial in Britain to raise to hero-status the ordinary troops.

The Crimean War brought about a sea change in Britains attitudes towards its fighting men. It laid the basis of the modern national myth built on the idea of the soldier defending the nations honour, right and liberty. Before the war the idea of military honour was defined by aristocracy. Gallantry and valour were attained by high-born martial leaders like the Duke of York, the son of George III and commander of the British army against Napoleon, whose column was erected in 1833, five years after the Dukes death, from the funds raised by deducting one days pay from every soldier in the army. Military paintings featured the heroic exploits of dashing noble officers. But the common soldier was ignored. Placing the Guards Memorial opposite the Duke of Yorks column was symbolic of a fundamental shift in Victorian values. It represented a challenge to the leadership of the aristocracy, which had been so discredited by the military blunders in the Crimea. If the British military hero had previously been a gentleman all plumed and laced, now he was a trooper, the Private Smith or Tommy (Tommy Atkins) of folklore, who fought courageously and won Britains wars in spite of the blunders of his generals. Here was a narrative that ran through British history from the Crimean to the First and Second World Wars (and beyond, to the wars of recent times). As Private Smith of the Black Watch wrote in 1899, after a defeat for the British army in the Boer War,

Such was the day for our regiment,