STUDIES OF NATIONALITIES IN THE USSR

Wayne S. Vucinich, Editor

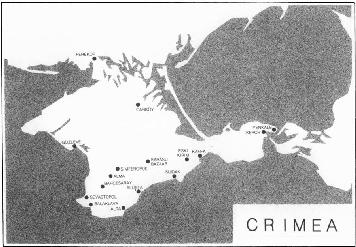

The Crimean Tatars

Alan W. Fisher

The Volga Tatars: A Profile in National Resilience

Azade-Aye Rorlich

The Kazakhs

Martha Brill Olcott

Estonia and the Estonians

Toivo U. Raun

Sakartvelo: The Making of the Georgian Nation

Ronald Grigor Suny

The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, founded at Stanford University in 1919 by the late President Herbert Hoover, is an interdisciplinary research center for advanced study on domestic and international affairs in the twentieth century. The views expressed in its publications are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, officers, or Board of Overseers of the Hoover Institution.

Hoover Press Publication 166

Copyright 1978 by the Board of Trustees of the

Leland Stanford Junior University

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher.

First printing, 1978

First paperback printing, 1987

ISBN 0817966625 (pbk.)

Manufactured in the United States of America

90 89 88 87 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Library of Congress has catalogued the

first printing of this title as follows:

Fisher, Alan W.

The Crimean Tatars / Alan Fisher. Stanford, Calif.: Hoover Institution Press, c1978.

xii, 264 p. : ill. ; 23 cm. (Studies of nationalites in the USSR) (Hoover Institution publication ; 166)

Bibliography: 231255.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-8179-6661-7

1. TatarsUkraineKrymska oblast. 2. Krymska oblast (Ukraine)History. I. Title. II. Series. III. Series: Hoover Institution publication; 166.

DK511.C7F497 947.717004943 76-41085

MARC

for Carol, Elizabeth, Christy, and Garrett

Contents

Foreword

In most surveys of the history of Russia and the Soviet Union, the more than one hundred non-Russian peoples receive far less attention than their histories and cultures merit. Moreover, such general works tend to give only superficial attention to such important topics as the Russian conquest of foreign nationalities and lands, the development and administration of ethnic minorities under Tsarist and Soviet rule, Russias role in transmitting both Russian and West-European ideas and institutions to their own Asian and non-Slavic groups, and Russias character as a melting pot of different ethnic peoples and cultures.

The Crimean Tatars is the first in a series of volumes that discuss the history and development of the non-Russian nationalities in the Soviet Union. The subject of this book is especially appropriate for the opening volume of the series, because a study of this particular people vividly illustrates a number of the problems encountered by Soviet leaders in their attempt to create a multinational society. Except for the Volga Germans, the Crimean Tatars are the only one of the component nationalities of the USSR who, having once been granted an autonomous territory, appear to have had this privilege permanently revoked.

The problems discussed here have parallels which are examined in the remaining volumes of the series. Since the beginning of the rapid industrialization of the Soviet Union, the requirements of economic development and political control have transformed the ethnographic map of the Soviet Union and created in many national autonomous territories situations nearly as acute as that in the Crimea. Many of the nationality groups have found themselves outnumbered and politically displaced by immigrating Great Russians, Ukrainians, and others. This movement of peoples and its results has called into question the functioning of the Soviet federal solution and has created discontented local nationalisms to plague the rulers in the Kremlin.

A new pattern, however, is now emerging. The difference in birth rates between the dominant Slavs and the non-Russian nationalities is changing the ethnographic balance more and more in favor of the latter. It appears possible or even likely that in the relatively near future the Great Russians will be outnumbered by the other nationalities.

As a result of these dynamics of development the study of the past and present of the non-Russian nationalities is extremely important. It is also significant in what it portends for the future. Thus, studies such as the one presented here, and those that follow, should provide the Western reader with a fuller understanding of the complexities of Soviet reality. Comparable volumes on several other major nationalities, a total of seventeen, are currently in preparation. Included are separate studies of the principal nations of Soviet Central Asia, the Caucausus, the Baltic region and the Ukraine, as well as special groups such as the Jews and the Crimean Tatars. Each volume examines the history of a particular national group in both the Tsarist and Soviet eras with an emphasis on determining its place in the Soviet federation as well as its impact on the evolution of Soviet society.

Hoover Institution

W AYNE S. V UCINICH , editor

Preface

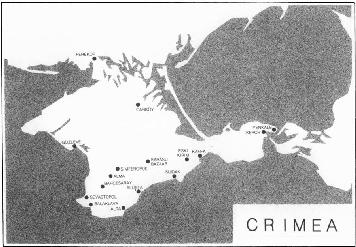

The Crimean Tatars are today a nationality living in a diaspora. Denied the right to return to their homeland in the Crimean peninsula, their communities are scattered throughout the USSR, the Turkish republic, and the West. Like other nationalities that have experienced the same disasters (the Jews come to mind), the Tatars claim to national identity and a national home are based on historical, cultural, and linguistic foundations.

Appearing first in the Crimea in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the Crimean Tatars soon displaced the existing political and cultural entities with their own; they established their first state there in the middle of the fifteenth century. From that time until the Russian annexation of the peninsula in 1783, the Crimean Tatars organized and lived in a state, called the Crimean Khanate, that was ruled by their own Giray dynasty. From 1783 until 1918, the Tatars lived within the Russian Empire as subjects of the tsars.

During the latter period, the Tatars were displaced gradually by immigrating Slavic settlers, officials, and landowners. Despite concerted efforts by their Russian rulers to eliminate Tatar culture and identity and to assimilate them into the fabric of Russian society, the Tatars were able to preserve their national awareness. With the fall of the tsarist system, the Tatars were temporarily successful in reestablishing their own state and independent society. But the advent of Bolshevik power soon put an end to their success, if not to their efforts.

Since 1920, the Crimean Tatars have experienced one calamity after another: collectivization and its related famines, the elimination of their political and cultural elites between 1928 and 1939, the ravages of war and occupation from 1941 to 1944, and finally, their wholesale deportation to remote areas of the USSR where they now reside. Yet there have been developments in the Tatar community that show accomplishment in the face of adversitydevelopments that show that the Tatars possess almost unequalled courage to struggle for what they consider to be a just solution to their problems. Applying pressure upon the Soviet authorities who were responsible for the denial of their national existence, they have succeeded in the years since 1944 in gaining partial restitution of what was taken from them by Stalin. In 1967, in a decree issued by the Soviet government, the charges made against the Tatars in 1944 were removed; they were rehabilitated as a nationality. Yet their rehabilitation was virtually meaningless, for the punishments under which they suffered were not removed. They cannot return to their homeland. Their national and cultural rights remain denied to them, and their struggle for these rights continues today.

Next page