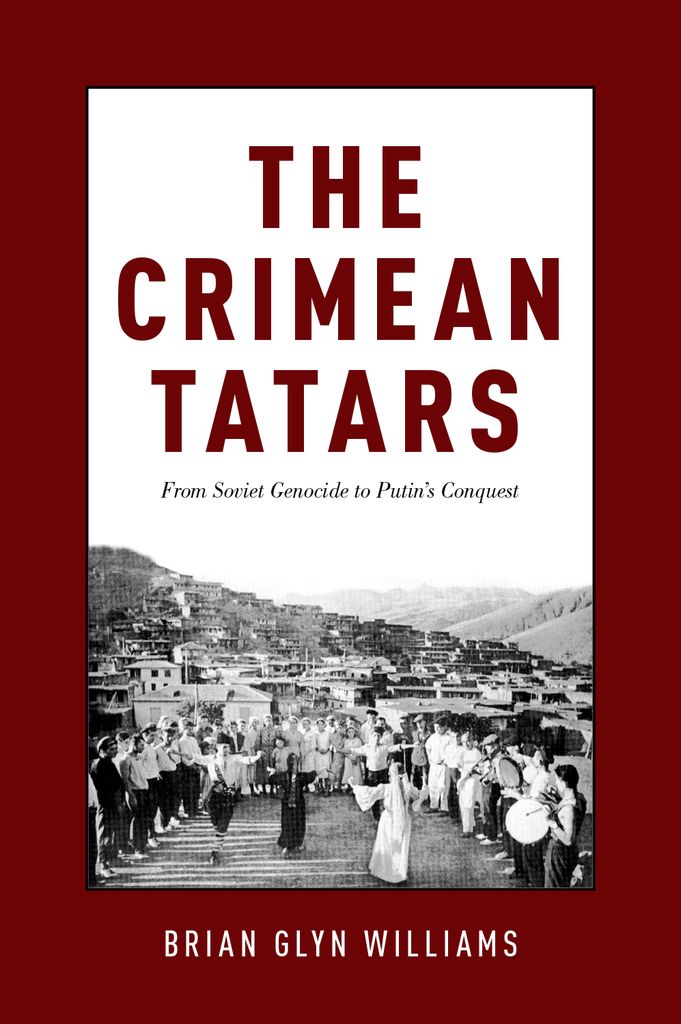

THE CRIMEAN TATARS

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016,

United States of America

Published in the United Kingdom in 2016 by

C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.

Copyright Oxford University Press 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

ISBN 978-0-19-049470-4

eISBN 978-0-19-049472-8

A copy of this books Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress.

For Eren Pasha Altindag, Yetkin Altindag, Feruzan and Kemal Altindag and Ryan and Justin Williams

CONTENTS

First and foremost I would like to thank the numerous Crimean Tatars who invited me into their simple stone homes in the settlements of the Crimea and greeted me with their peoples legendary hospitality, despite their often tragic circumstances. In particular, I would like to thank Nuri Shevkiev and his wonderful wife Lilia and his children Emir and Elmaz for letting me live with them in their samostroi (self-built) home in the settlement of Marino near Simferopol. I still fondly recall the evenings gathered with the Shevkievs and Tatars from the surrounding houses eating homemade cigborek and drinking tea while collecting stories of the deportation, exile and return.

I would also like to thank Mustafa Dzhemilev for taking the time to grant me interviews during my stay. It was a real honor to get to know the Crimean Tatar Mandela who sacrificed so much to lead his people from exile to their homeland. I would also like to thank Lilia Bujurova, Izzet Khairov, Alie Akimov, Fevzi Yakubov, Abdullah Balich, Reshat Dzhemilev and Server Karimov for the time they took to grant me interviews.

In addition, I would like to thank my parents, Donna and Gareth, for encouraging me to travel the world as a young man and to respect other cultures. I would not be who I am today without their inspiration and guidance over these many years. I am also grateful to my wife Feyza Altindag for her support and patience with my obsession with the Crimean Tatars history.

I also owe a huge debt of gratitude to my advisors at the University of Wisconsin who taught me Central Asian history, Uli Schamiloglu and Kemal Karpat. I would also like to say thanks to my colleagues at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth, Mark Santow and Len Travers, who provided me with the invaluable support I needed to produce this work. And as always I owe a huge debt of gratitude to my indispensable secretary, Sue Foley.

On the distant edge of Europe, where East meets West, Islam meets Christianity, and the world of the steppe nomad meets that of settled man lies the Crimean Peninsula. Since even before the classical era, when intrepid sailors from Greece arrived on its shores and interacted with the mysterious horse-riding peoples of the vast European plains who migrated to the Crimeas interior, this borderland has been an outpost of the nomads from the east. It has also been a preserve of nations, an ethnic time capsule and palimpsest of lost Eurasian races.

Located on the Black Sea shore of the Ukraine (whose name translates to the Frontier of the steppe in Russian), the Crimea has seen more than its share of conquering and migrating races. These races have, like waves coursing across the open steppes from the north and east, lapped up on its plains and cast their ethnic residue on the Crimeas genetic makeup.

It was here that the ancient Greek traders encountered the Scythian nomads, whose skill as horse-mounted archers gave birth to the legend of the half-horse, half-man Centaurs. After the Scythians came the nomadic Sarmatians, the Goths and Attilas Huns, followed by the Turkic Kipchaks (or Polovtsians, the Men of the Plains as they were known in Russian). But no nomadic race left as great an impact on the Crimea as the world-conquering Mongols. Storming across the Eurasian steppe from their home in distant Mongolia, the Mongols of Batu Khan (grandson of Genghis Khan) shattered the divided Russian principalities in the forests to the north and absorbed the vast hordes of Kipchak Turks of the south Ukrainian plains into their armies in the 1240s. The amalgam of pagan Mongols and Turkic Kipchaks then gradually converted to Islam and became known as Tatars.

It was these horse-riding Turko-Mongol-Muslim Tatars that were to call the Crimea home until the present day. As the transcontinental Mongol world empire fractured and collapsed in the mid to late 1300s, the Tatars of the Crimea and surrounding steppes continued to dominate much of Eastern Europe. While the Mongols were ultimately expelled from China and the Middle East in the mid fourteenth century, in the southern Ukraine the Tatars were an anachronism that continued their horse riding ways for centuries.

Not even the liberation of Russia to the north from the Tatar Golden Horde in 1480 ended the power of the Crimean Tatars. By this time Khans (Genghisid rulers) of the Tatar Giray dynasty had established an independent Khanate in the Crimea and surrounding lands. The Tatar Khans of the Crimea, ruling from the fabled town of Bahcesaray (Garden Palace) in the southern Crimean mountains, saw the rising power of Russia and made a far-sighted alliance with another up-and-coming power, the Muslim Ottoman Empire. This alliance helped the Crimean Tatars maintain their independence even as Ivan the Terribles Russia inexorably expanded eastward across the vast forests of Siberia and down to the Caspian Sea, conquering the other Tatar remnants of the Mongol Golden Horde. Long after the Tatars of the Volga River region and plains north of the Caspian Sea had been absorbed into sixteenth-century Russia, the Crimean Tatars maintained their independence.

As the memory of the Medieval Mongols faded in other parts of the world, the Crimean Tatars continued to roam freely on the plains on the edge of a modernizing Europe. Riding on their rugged steppe steeds with their fur rimmed, spiked helmets on chambuls (raids for cattle and slaves), the Tatars of the Crimea continued their ancient ways and kept the Russians off the open plains of southern Ukraine for centuries. The Tatars of the Crimea were able to burn Moscow as late as 1571. Every year the Tatars would sally forth from their bastion in the Kirim (the Fortress, the Turko-Mongol name which gives us the English word Crimea) to carry out vast slave raids into Poland, Russia and the Ukraine. Not even the modernizing Tsar Peter the Great could conquer the horse-riding Crimean heirs of Genghis Khan. In fact, the Crimean Tatars played a major role in the Turkish defeat of Tsar Peters invasion of Ottoman Eastern Europe in 1711.