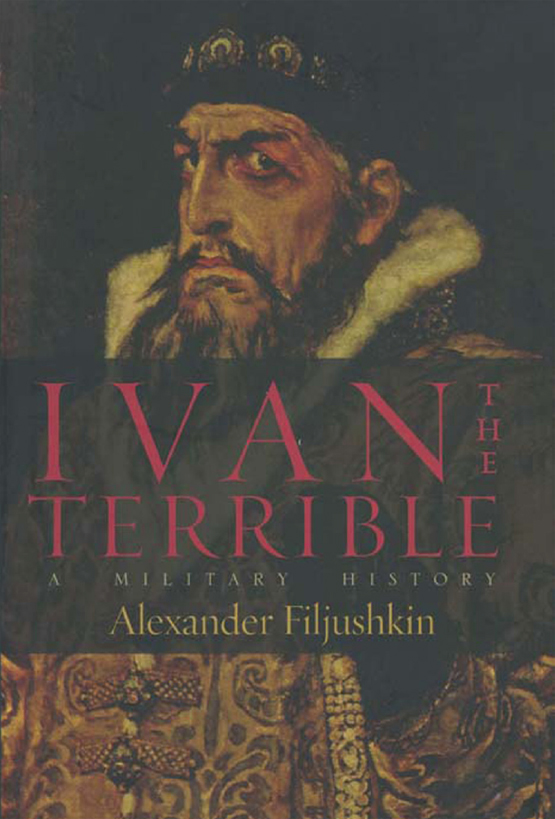

All maps Alexander Filjuskin, 2008.

Please note that these maps are intended as sketches to aid the reader and are not drawn to scale.

I would like to thank all my friends and colleagues who have helped me while writing this book. I am particularly grateful to Alexey Lobin (Russia), Anti Selart (Estonia), Andrey Yanushkevich (Byelorussia), William Urban (USA), Sergey Bogatyrev and Michael Leventhal (Great Britain). Special thanks also to the Russian historical journal Rodina and its editor, Yury Borisenok, for permission to use many of the illustrations, which are the property of this publishing house. And I would like to thank Kate Baker, of Frontline Books. Her advice and skilled assistance made my work on the book thoroughly enjoyable.

My obligation to Olga Uverskaya, Alexander Mitrophanov and Galina Yakovleva is considerable. The translation of this book has been possible only with their help. Olga Uverskaya has worked on the Introduction and and the Epilogue. It is also important to thank Philip Sidnell for all his hard work and meticulous editing, which considerably improved the text. He saved me from many complicated problems and I am most grateful.

My creative labour was only made possible by the support of my family. My apologies that I was so pressed for time and did not find enough time for them; they deserve better. The encouragement of my wife, Svetlana Smirnova, was great, and I finished the book thanks to her above all others. My sons, Egor and Fedor, showed patience and indulged their fathers work. And my mother, Svetlana Filjushkina, unquestioningly trusted in my abilities to perceive the military policy of Ivan the Terrible, even when I wasnt sure that it was possible for an ordinary person to comprehend the cruel deeds of the first Russian tsar.

At the heart of different parts of this book lies my research, supported by several scientific organisations at various points in my life. Initially, it was St Petersburg State University and Voronezh State University. Then I received grants from the American Council of Learned Societies (1999 and 2000); a Queen Yadwiga scholarship from the Jagellonian University (Krakow, Poland, 2000), grants from the Russian Ministry of Education (20012002), Russian scientific organisation ANO-INOCENTER with the support of Keenans Institute, Carnegie Corporation and Foundation of the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation (USA, 2004); and a scholarship from the German Gerda-Henkel Foundation (20042006). I am exceedingly grateful to all these organisations.

Alexander Filjushkin

Berlin, St Petersburg, Tolmachevo, 2008

Having been told that the pope had huge authority all over the world, Joseph Stalin narrowed his eyes cunningly and asked: And how many divisions does the pope have? These words reflect the criterion by which a countrys political significance has been appraised in Russia since ancient times: military power. The size and quality of the armed forces, their ability to win wars, have always been appreciated more than any other characteristics of the states level of development and higher than the ability of the country to gain the sympathies of its neighbours and maintain friendly relations with them. Knowing this, we must admit that Russian politicians of the late nineteenth century had reason to say: Russia has only two allies: its army and its navy.

When did the Russian military factor start playing its role in world and European history? In, for example, the early Middle Ages, throughout the Crusading era (10951291), the Hundred Years War (13371453), the Wars of the Roses (145585), the West did not know anything about Russian armies. Minor wars against Sweden and German military orders in the Baltic region, like the casual clashes with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, were just local conflicts of which Europe had only very vague notions. Nobody could see in those insignificant campaigns what later would be called a Russian military threat.

It was only towards the end of the fifteenth century that, as Karl Marx wrote:

Astonished Europe, at the commencement of Ivans reign [Ivan III]

Grand Prince Ivan III (German

engraving, sixteenth century)

A contemporary Russian philosopher, Vadim Tsimburski, interprets Russias entrance onto the world stage in the fifteenth century as a geopolitical blast: The Russians exploded the old intra-continental Eurasia of nomads. As a result of this explosion, the entire historical development of eastern Europe, from the fifteenth century to the present day, has been inextricably connected with Russias influence.

However, Ivan IIIs time was merely a prelude to the moment when Europe started talking of Russian wars. Ivan III was concerned with internal problems rather than with external ones. He was primarily engaged in consolidation of Russian lands and creation of the new Russian state. The main enemy at the time was the disintegrating Golden Horde, from which Ivan claimed independence in 1480. In 1502 Ivan managed to defeat one Tatar state using the forces of another one: the Crimean khan, acting as the Great Prince of Moscows ally, beat the Great Horde by the River Tikhaja Sosna and put an end to its existence as a state. Russias participation in international coalitions against the Habsburgs, in 148391 and 149298, was exclusively financial and diplomatic in nature. Some minor wars on the outskirts of Europe (for instance, with the Livonian Order in 15003) were just a latent symptom of a future westward advance.