Ivan the Terrible

IVAN

THE TERRIBLE

Robert Payne

and Nikita Romanoff

All pictures except where otherwise credited were obtained in the Soviet Union.

First Cooper Square Press edition 2002

This Cooper Square Press paperback edition of Ivan the Terrible is an unabridged republication of the edition first published in New York in 1975. It is reprinted by arrangement with the Estate of Robert Payne and with coauthor Nikita Romanoff.

Copyright 1975 by Robert Payne and Nikita Romanoff

Designed by Ingrid Beckman

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permissions from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

Published by Cooper Square Press

A Member of the Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group

200 Park Avenue South, Suite 1109

New York, New York 10003-1503

www.coopersquarepress.com

Distributed by National Book Network

A previous edition of this book was catalogued as follows by the Library of Congress:

Payne, Pierre Stephen Robert, 1911

Ivan the Terrible.

Bibliography: p.

1. Ivan IV, the Terrible, Czar of Russia, 15301584. 2. RussiaHistoryIvan IV, 15331584.

I. Romanoff, Nikita, joint author.

DK106.P39 | 947.040924 | 74-13374 |

ISBN: 978-0-8154-1229-8

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

For Janet and Patricia

Contents

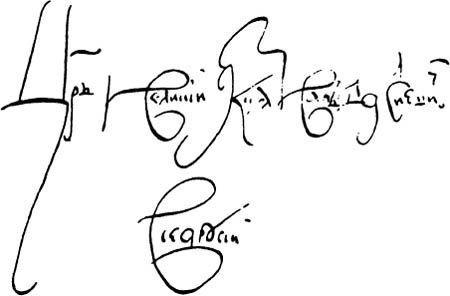

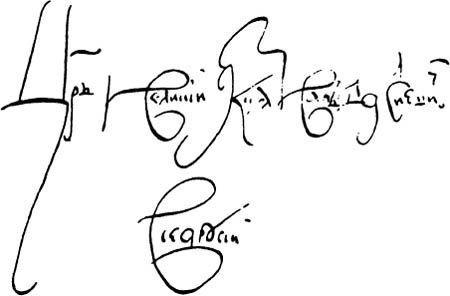

Ivans signature. Some historians believe he never signed documents, but ordered his chief secretary to sign for him. It reads: Tsar and Grand Prince Ivan Vasilievich of all Russia.

The Grand Prince Vasily III

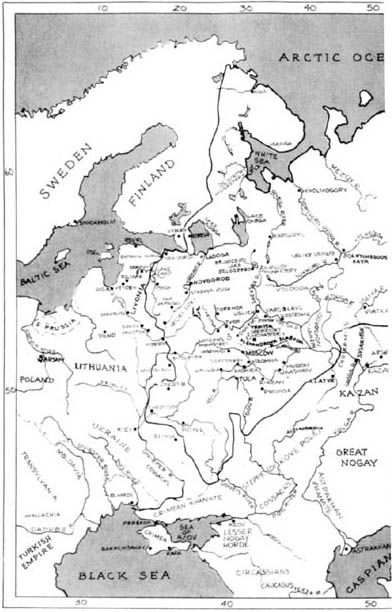

OF ALL THE PEOPLE in Russia the Grand Prince Vasily III regarded himself as the most miserable. He could trace his descent back to Rurik, the legendary founder of the Russian state, and through his mother, Sophia Palaeologina, to a long line of Byzantine emperors, but he had neither sons nor daughters to continue the line. One day, walking in the countryside around Moscow, he saw a birds nest and gazed at the chicks with a feeling of shame. Whom do I resemble? he asked. Not the birds of the air, for they are fertile. Not the beasts of the earth, for they produce young ones.... A few days later, talking to his boyars, he again bewailed his fate. Who will rule after me in the Russian land, in all my cities, within my frontiers? he exclaimed. Shall I give them up to my brothers? But they do not know how to order affairs in their principalities! The boyars replied: Lord, Grand Prince, the barren fig tree must be cut down and cast out of the orchard!

The Grand Prince Vasily III was a mild-mannered prince, well-liked by the people. Unlike his more famous father, Ivan III, known to history as Ivan the Great, who conquered large territories and fought the Tatars, Vasily III possessed none of the gifts of a conqueror. He had fought desultory wars against Lithuania, drawn Pskov, Smolensk, and Ryazan into his kingdom, and shown himself to be a cautious and sensible man who rarely permitted himself the luxury of showing his full strength. A portrait of him on the walls of the Cathedral of Michael the Archangel, which he built at the beginning of his reign, depicts him as a tall, heavy-set man, sad-eyed and vulnerable, with pursed lips and a huge beard which flows heavily across his chest. He wears an air of settled melancholy and looks more somber than any of the other somber figures who crowd the cathedral walls.

His wife, the Grand Princess Salomonia, the daughter of a rich boyar, was regarded at the time of her marriage as the most beautiful woman in Russia. She was devout, gentle, and loving, and no one had found any fault in her. Now at the age of forty-seven, having reigned for nearly a quarter of a century, the Grand Prince found a fault in her that was beyond curing. She was barren and must be cast out of the orchard. She protested that she had committed no crime, it was Gods will that she was barren, the Church categorically forbade divorce on the grounds of barrenness alone. She had powerful allies. They included the Metropolitan Varlaam, the great theologian known as Maxim the Greek, and Prince Simeon Kurbsky. The Metropolitan was banished to a monastery in the far north, Maxim the Greek was put on trial on the charge of heresy and banished to Tver, and Prince Simeon Kurbsky was banished from court. The Grand Princess Salomonia was divorced and sent to a nunnery in Suzdal. It was said that she raged against the injustice of her divorce to the very end and cursed the husband who had cast her out. It was said, too, that an even more terrible curse was laid on him. Mark, Patriarch of Jerusalem, heard about the coming divorce and thundered: If you should do this evil thing, you shall have an evil son. Your nation shall become prey to terrors and tears. Rivers of blood will flow, the heads of the mighty will fall, your cities will be devoured by flames. And all this came about.

Vasily III entered upon his new marriage joyfully and light-heartedly. His bride was Princess Elena Glinskaya, by origin Lithuanian, now living as a refugee in the Russian court. She was the ward of her uncle, Prince Mikhail Glinsky, whose adventurous career had led him to fight in the armies of the Emperor Maximilian and Albert of Saxony. His ward was about twenty, strong-willed, exuberant, beautiful. To please her the Grand Prince shaved off his beard, even though the Orthodox Church regarded it as a sin for a man to shave off his beard. But though he doted on her, he was not especially enamored of her family. Prince Mikhail Glinsky was at that time spending his days in a Russian prison; he had been arrested for treason, he was in chains, and his lands were confiscated. He was not finally released until February 1527.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.481992.